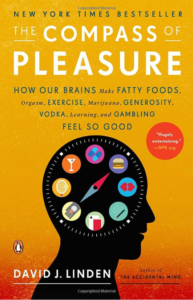

“Philosophers like the Epicureans, St. Augustine, and Nietzsche have tried to analyze and comprehend this elemental fact of our experience, but it is only recently that we have been able to study it empirically, thanks to remarkable advancements in neuroscience. In The Compass of Pleasure, David J. Linden, explains the recent research that has enabled us to understand how the brain’s pleasure circuits are engaged by our vices and, surprisingly, our virtues.”

– Dust jacket front blurb from The Compass of Pleasure: How Our Brains Make Fatty Foods, Orgasm, Exercise, Marijuana, Generosity, Vodka, Learning, and Gambling Feel So Good

I am coming up on approximately my first year since deciding to go deep into the study of Epicurean philosophy. In that time, I have learned a lot about the history of the development of pleasure ethics, from Plato’s Philebus, to Aristippus and the Cyrenaics, through to Epicurus’ more nuanced theory. However, I think that since we are living in the age of modern science, it could be useful for us to draw on the recent knowledge coming from the field of experimental neuroscience to inform and shape our understanding of pleasure ethics. It could be that modern science confirms, rejects, or at least further contextualizes the principles that were reasoned by the ancients but which could not be explored empirically until only recently. That thinking is what led to my review of this book.

The prologue to the book opens with an amusing story recounting a time when the author went travelling in Thailand. When he boarded one of the three-wheeled motorcycle taxis, the driver asked him essentially ‘what’s your pleasure?’, and proceeded to offer him a litany of contraband and illicit sexual opportunities. This triggered in his mind the question of why it is that we are such ‘dopamine fiends’, or why we go looking for pleasures of all varieties.

“We humans have a complicated and ambivalent relationship to pleasure, which we spend an enormous amount of time and resources pursuing. A key motivator of our lives, pleasure is central to learning, for we must find things like food, water, and sex rewarding in order to survive and pass our genetic material to the next generation. Certain forms of pleasure are accorded special status. Many of our most important rituals involving prayer, music, dance, and meditation produce a kind of transcendent pleasure that has become deeply ingrained in human cultural practice.”

Chapter 1: “Mashing the Pleasure Button”

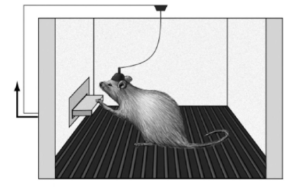

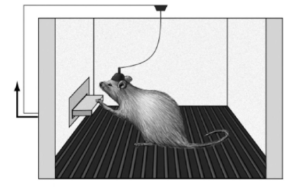

This first chapter is an extended history lesson about past efforts to experiment (occasionally highly unethically by modern standards) with pleasure stimulation in animals and humans. He recounts the experiments by Hebb, Olds, and Milner starting in 1953, which involved implanting electrodes in the brains of rats and then sending electrical stimulation to specific brain regions when the rat pressed the lever. What they found was that the rats would over time become trained to seek the lever and be stimulated, and, dramatically, that the rats would furiously press the lever as many as thousands of times per hour to satisfy their fixation. They would choose the electrostimulation over food, over water, over sex, over parenting their offspring, to the point of death.

Eventually by 1972, these sorts of experiments were tried on humans, with the highly unethical goal of “bring[ing] about heterosexual behavior in a fixed, overt homosexual male.” The patient B-19 was hooked up with electrodes implanted directly at nine sites in his brain. When he was given the freedom to regulate his own stimulation, he would mash the button “like an eight-year-old playing Donkey Kong”. The author writes:

“This study is morally repugnant on many different levels — the profound arrogance of attempting to “correct” someone’s sexual orientation, the medical risk of unjustified brain surgery, the gross violations of privacy and human dignity. Fortunately, homosexual conversion therapy with brain surgery and pleasure center stimulation was soon abandoned.

Stepping back a bit, what we are left with, from this and a handful of other studies, is an appreciation of the immense power of direct electrical stimulation of the brain’s pleasure circuitry to influence human behavior, at least in the near term.”

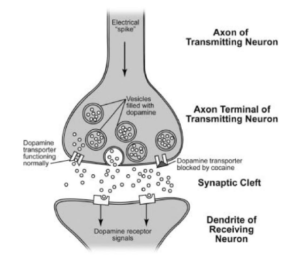

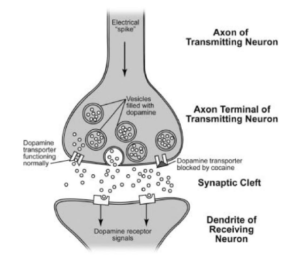

He then gives an account of the underlying neuroscience of pleasure, which originates with signaling from neurons stemming from the ‘ventral tegmental area’ (VTA) in the brain. These electrical impulses move along the fibrous axons until they arrive at terminals. When they reach the terminals, the neurotransmitter dopamine is released from its stores in the terminal into the surrounding space, called the synaptic cleft. The dopamine then binds onto the target neuron’s dopamine receptors, and those which do not bind are then returned to the transmitting terminal in a process called ‘reuptake’ and are recycled for later use.

The molecules associated with certain drugs are able to prevent this reuptake process, which allows the stream of dopamine to cross the cleft more efficiently, and explains why these drugs are experienced as intensely euphoric and pleasurable. The author writes that the central insight of these diagrams is that:

“Experiences that cause the dopamine-containing neurons of the VTA to be active and thereby release dopamine in their targets (the nucleus accumbens, the prefrontal cortex, the dorsal striatum, and the amygdala) will be felt as pleasurable, and the sensory cues and actions that preceded and overlapped with those pleasurable experiences will be remembered and associated with positive feelings.”

These experiences remind me of what Epicurus refers to as kinetic pleasures, or the pleasures of variation and ‘motion’. Such pleasures include any of those that arise after some stimulus has impinged upon our senses, such as hearing a string quartet, licking an ice cream cone, petting a fluffy animal, gazing up at beautiful architecture, or smelling a lovely perfume. However, they are not limited to just those bodily pleasures that affect our senses, but also the mental pleasures such as remembering or anticipating pleasant experiences. These also have the power to trigger our dopamine response.

Chapter 2: “Stoned Again”

This chapter is about the different kinds of drugs and why we become addicted to them:

“All cultures use drugs that influence the brain. They range from mild stimulants like caffeine to drugs with potent euphoric effects, like morphine. Some carry a high risk of addition, some do not. Some alter perception, others mood, and some affect both. A few can kill when used to excess. The specific attitudes and laws relating to psychoactive drug use vary widely among cultures. . . “

He gives a number of historical and cross-cultural examples of drug use to illustrate his point. The first story used to illustrate the timelessness of human drug addiction is the (hitherto unknown to me but humorously surprising) case of the Stoic Emperor Marcus Aurelius’ addiction to opium:

“Perhaps it was easier to be a Stoic while stoned: The emperor was a notorious opium user, starting each day, even while on military campaigns, by downing a nubbin of the stuff dissolved in his morning cup of wine. Writings by Galen suggest that Marcus Aurelius was indeed an addict, and his accounts of the emperor’s brief periods without opium, as occurred during a campaign on the Danube, provide an accurate description of the symptoms of opiate withdrawal.”

Another interesting example of a drug used that is non-addictive and non-pleasure activating is DMT (or ayahuasca), administered in shamanic rituals by the tribes of the Amazon rainforest, which has the power to induce horrifying images in the mind (but with the therapeutic aim of overcoming these fears).

He distinguishes between those drugs that do light up our pleasure center in the brain and those that do not. As it turns out:

“Those psychoactive drugs that strongly activate the dopamine-using medial forebrain pleasure circuit (like heroin, cocaine, and amphetamines) are the very ones that carry a substantial risk of addiction, while the drugs that weakly activate the pleasure circuit (like alcohol and cannabis) carry a smaller risk of addiction. Drugs that don’t activate the pleasure circuit at all (like LSD, mescaline, benzodiazepines, and SSRI antidepressants) carry little or no risk of addition. This pleasure gradient also correlates strongly with the willingness of animals to work for these drugs.”

He also explains why only mildly-euphoric drugs like nicotine, taken in small but frequent doses, tend to be more addictive than infrequently used highly-euphoric drugs like injected heroin. It boils down to the user’s desire to achieve a comparable level of pleasure: since cigarettes are only mildly pleasant, it takes more of them to achieve a comparable dopamine hit, and the repetition of continuously exposing one’s brain to the stimulus creates dependency. He defines drug addiction as “persistent, compulsive drug use in the face of increasingly negative life consequences” and argues that addiction should be treated as a medical issue:

“When we say that addiction is a disease, aren’t we just letting addicts off the hook for their antisocial choices and behaviors? Not at all. A disease model of addiction holds that the development of addiction is not the addict’s responsibility. However, crucially, recovery from addiction is.”

From the Epicurean point of view, careful attention needs to be paid to the enjoyment of certain psychoactive drugs, and the information in this chapter is relevant to making prudent and informed decisions using the method of hedonic calculus. Additionally, we should look sympathetically towards those who are hooked on substances, because the path to recovery is arduous.

Chapter 3: “Feed Me”

This subject of this chapter is: ‘Why do we enjoy eating, how is eating regulated in the brain, and why do some people struggle with eating habits?’

The first task is to dispense with the myth of blood glucose as the primary trigger for the onset of feeding. The author says that “eating is biochemically induced only in cases of severe starvation,” and that under normal circumstances, there are other drivers of food regulation. This reminds me of a quote from Porphyry:

“Do not think it unnatural that when the flesh cries out for anything, the soul should cry out too. The cry of the flesh is, “Let me not hunger, or thirst, or shiver,” and it’s hard for the soul to restrain these desires. And while it is difficult for the soul to prevent these things, it is dangerous to neglect nature which daily proclaims self-sufficiency to the soul via the flesh which is intimately bonded to it.”

– Porphyry, Letter to Marcella

Addressing the last question first, the author explains how one contributor towards obesity is a deficiency in the hormone leptin. Leptin is secreted by fat cells that helps to regulate appetite and energy expenditure in the brain. When less fat cells are present, less leptin circulates in the body, which causes the desire for more food and less energy expenditure, resulting in weight gain. On the other hand, if there are an excess of fat cells present, more leptin in the blood is registered and so feeding is suppressed and metabolism and activity are increased to burn more energy.

“While the leptin homeostatic system explains how the brain can receive information about long-term changes in weight as indicated by body fat, it doesn’t account for the short-term regulation of appetite.”

In the short term, feeding is regulated by the feeding control circuit, taking place in the hypothalamus. There are two competing hormones, CRH which signals for hunger and orexin which signals for satiety. These hormones are in competition with one another. He likens the competition between these two signals to “an old-fashioned bathtub with separate hot and cold water taps: the temperature of the bath is then determined by the relative flow of hot and cold water.”

Okay, but this all sounds very deterministic, as if we were just biological machines responding to chemical circumstances and states in our brain. Don’t we have free will in all matters? This is what Linden has to say on that:

“The idea that eating is primarily a conscious and voluntary behavior is deeply rooted in our culture. We humans are invested in the notion that we have free will in all things. We want to believe that weight can be controlled by volition alone. Why can’t that fat guy just eat less and exercise more? He just lacks willpower, right? Not at all. Our homeostatic feeding control circuits make it very hard to lose a lot of weight and keep it off.”

We should not be too hard on ourselves or others who are struggling with diet and weight management. We can try to train ourselves to rely on less food, but not all people will be capable of doing so without medical intervention.

However, the first question has still not been addressed. Does the pleasure circuit activate during the naturally pleasant act of eating? “The answer is clearly yes,” says Linden. Eating releases a surge of dopamine:

“These studies revealed not only that eating was associated with dopamine release, but also that the degree of dopamine release could be used to predict how pleasurable the subject rated the experience of eating. Different foods produced different levels of dopamine release, a finding that correlated with the reported pleasures of eating. . . . Also, as hungry subjects continued to eat and became sated, the amount of dopamine released in the dorsal striatum was reduced. Not surprising: The first bites of a meal give the most pleasure when you’re hungry.”

This means that certain foods are more pleasant to eat than others, and the amount of pleasure experienced diminishes as eating proceeds, with that first bite being the most delicious. However, after the eating has occurred, it would seem that the feeling of satiety is the same regardless of what food was consumed. This reminds me of some lines from the Letter to Menoeceus:

“Just as he does not choose the greatest amount of food but the most pleasing food, so he savors not the longest time but the span of time that brings the greatest joy.”

“So simple flavors bring just as much pleasure as a fancy diet if all pain from true need has been removed, and bread and water give the highest pleasure when someone in need partakes of them.”

Later in the chapter he talks about how stress can lead to overeating. It does so by causing a complicated cascade of hormonal signaling that results in corticosterone passing into the brain, triggering the feeling of stress that leads to overeating. One possible remedy to this is to try out “behavioral strategies for stress reduction, like meditation or exercise, [that] can reduce the amplitude of stress hormone surges and are thereby effective in reducing stress-triggered overeating.”

So there is a utility to practices like meditation, which can help regulate our stress levels. An Epicurean meditation can consist of contemplation of the Epicurean gods or on the meaning of the Kyriai Doxai.

Chapter 4: “Your Sexy Brain”

“When I’ve spoken about our human behavior in regard to drugs or food, I’ve indicated that we’re basically the same as other mammals. While we have a bigger neocortex than a mouse or a monkey, and therefore a greater ability to counteract our subconscious drives with cognitive control, at the root our responses to food and psychoactive drugs are the same as those of our distant mammalian relatives. The same is not true of our mating system.”

This chapter looks at the experience of sex, sexual patterns, and sexual addiction (by now you might be finding a pattern in this book – he is very interested in how harmful behavioral patterns form). In humans, unlike some of the other mammals, sex is frequently recreational. Additionally, most of the other mammals are promiscuous, whereas humans tend to be monogamous. Homosexuality is another trait present in humans that can be found in animals. Looking towards our primate cousins, the author observes the following about bonobos:

“In bonobos, it seems as if homosexual behavior, in addition to providing sexual pleasure, also fulfills a social role by diffusing tension and promoting social bonding at the expense of aggression.”

So it seems that a variety of different orientations (heterosexual vs homosexual, etc.) and mating style tendencies (monogamous vs non-monogamous) can be found in the animal kingdom, as well as in humans.

Linden continues by examining the properties of sexual addiction. He regrets to observe that in our society, the sexually addicted have a low probability of seeking help due to social stigma. Sexual addiction is a very real phenomenon that has terrible consequences for not only those people who become addicted but also those people who are treated as means to the end of satisfying the addiction.

Regarding these topics, Metrodorus has this to say:

“[addressing a young man] I understand from you that your natural disposition is too much inclined toward sexual passion. Follow your inclination as you will, provided only that you neither violate the laws, disturb well-established customs, harm any one of your neighbors, injure your own body, nor waste your possessions. That you be not checked by one or more of these provisos is impossible; for a man never gets any good from sexual passion, and he is fortunate if he does not receive harm.”

Before we view this as a directive against any sort of sexuality whatsoever, we must appreciate the context in which this was written: a world without contraception, STD protection, and traditional social mores and regulations. If Metrodorus could see the context of today’s world, it is likely he would not be so hard on modern Epicureans who wish to satisfy their natural desires harmlessly. Care must be taken so as not to become sexually addicted.

Chapter 5: “Gambling and Other Modern Compulsions”

This chapter is about other miscellaneous compulsions, including a diverse range of addictions, such as addiction to the Internet, gambling, pornography, chocolate, consumerism, etc. One of the central questions he is attempting to address is why is it that abstract concepts (that are not immediately sensible) are perceived as pleasant. He presents a number of experiments to explore these matters in detail, such as experiments in reward association in monkeys. He concludes by saying that:

“This chapter has seen our ideas of the dopamine pleasure circuit extended in some provocative directions. Initially it seemed that the pleasure circuit was either naturally activated by intrinsically adaptive stimuli like food, water, or sex, or artificially engaged by drugs or stimulating electrodes placed deep within the brain. We also discussed how the development of addiction could slowly modify the structure and function of the pleasure circuit and thereby drain the pleasure out of any of these activities, replacing liking with wanting. These observations are all true, but they don’t tell the whole story.

We now know from Schultz’s monkey experiments that rapid associative learning can transform a pleasure signal into a reward prediction error signal that can guide learning to maximize future pleasure. It is likely that this same process is what enables humans to feel pleasure from arbitrary rewards like monetary gain (or even near misses in monetary gain) or winning at a video game.”

So it seems that we do have the capacity to experience mental pleasures that stem from the expectation of future reward. The Epicureans held that the pleasures of the mind can even exceed the pleasure of the flesh. The anticipation of a future pleasure can be a powerful motivator of behavior.

Chapter 6: “Virtuous Pleasures (and a Little Pain)”

This chapter is about the ‘virtuous’ pleasures – those pleasures that come with some voluntary effort but are overall good for us and our wellbeing, such as exercise, meditation, fasting, and philanthropic giving.

“Sustained physical exercise, whether it be running or swimming or cycling or some other aerobic activity, has well-known health benefits, including improvements in the function of the cardiovascular, pulmonary, and endocrine systems. Voluntary exercise is also associated with long-term improvements in mental function and is the single best thing one can do to slow the cognitive decline that accompanies normal aging. Exercise has a dramatic antidepressive effect. It blunts the brain’s response to physical and emotional stress.

Given these massive long-term benefits, it is clear that voluntary exercise is a useful component of one’s hedonic regimen. Although these activities may be strenuous in their performance, the subsequent advantages accrued are worth taking into consideration. Additionally, one may enjoy short-term benefits, such as “increased pain threshold, reduction of acute anxiety, and ‘runner’s high’, which is a short-lasting, deeply euphoric state that’s well beyond the simple relaxation or peacefulness felt by many following intense exercise.”

“Another virtuous pleasure that is culturally widespread and often linked to spiritual practice is meditation. . . .While meditation is certainly relaxing and is sometimes described as blissful, does it in fact activate the medial forebrain pleasure circuit? [One study] found a significant increase in dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens of their meditators. This result is suggestive, but it awaits both confirmation and extension to other forms of meditation.

What is clear about meditation is that it has the ability to reduce our stress, activate a large number of brain regions, and decrease the activation of other brain regions. What is still unclear is whether it triggers the release of dopamine. It is worth experimenting for yourself to see whether mediation can form a useful component of your hedonic regimen.

Can fasting also serve a role in our hedonic regimen? The staving off of eating for an increased period of time induces the body to enter a state of autophagy, whereby the body draws upon its stored resources to provide energy, hence burning fat. So fasting can help regulate body weight. Additionally, after one has fasted for a period of time, the amount of pleasure one experiences at the break of the fast may be impressive. Regarding fasting, Seneca had this to report about Epicurus:

“The great hedonist teacher Epicurus used to observe certain periods during which he would be frugal in satisfying his hunger, with the object of seeing to what extent, if at all, one thereby fell short of attaining full and complete pleasure, and whether it was worth going to much trouble to make the deficit good. At least so he says in the letter he wrote to Polyaenus in the archonship of Charinus {308 – 307 B.C.}. He boasts in it indeed that he is managing to feed himself for less than a half-penny, whereas Metrodorus, not yet having made such good progress, needs a whole half-penny!”

– Seneca, Letter to Lucilius

Partly through the chapter, the author dissects the claim by Jeremy Bentham that we are subjects of our masters, pleasure and pain:

“In the late eighteenth century the British philosopher Jeremy Bentham famously proclaimed,

“Nature has placed mankind under the governance of two sovereign masters, pain and pleasure. . . . They govern us in all we do, in all we say, in all we think: every effort we can make to throw off our subjection, will serve but to demonstrate and confirm it.”

The accumulating neurobiological evidence indicates that Bentham was only half correct. Pleasure is indeed one compass of our mental function, guiding us toward both virtues and vices, and pain is another. However, we now have reason to believe that they are not two ends of a continuum. The opposite of pleasure isn’t pain; rather, just as the opposite of love is not hate but indifference, the opposite of pleasure is not pain but ennui — a lack of interest in sensation and experience.

You don’t have to be a sadomasochistic sex enthusiast to know that pleasure and pain can be felt simultaneously: Recall Boecker’s aching but blissful long-distance runners, or women in childbirth. In the lexicon of cognitive neuroscience, both pleasure and pain indicate salience, that is, experience that is potentially important and thereby deserving of attention. Emotion is the currency of salience, and both positive emotions — like euphoria and love — and negative emotions — like fear, anger, and disgust — signal events that we must not ignore.”

So he contends that the opposite of pleasure is not pain but rather ennui, in this sense interpretable as a lack of excitement, and that pleasure and pain are both salient experiences, or having the quality of being important or prominent to respond to. For example, the sensation of pain in animals is often triggered by nociception, which is the response to exposure to noxious stimuli. In order to preserve the integrity of the endangered body part, the animal recoils and avoids the stimuli and experiences a feeling of pain.

Chapter 7: “The Future of Pleasure”

This chapter is about the future of pleasure as neuroscience and nanoscience research progress. The author is skeptical about the near term feasibility of nanobots invading our brains and simulating perfect-fidelity sensory experiences and virtual realities. He departs from the optimism of futurists like Ray Kurzweil, who think that the biotechnological revolution is coming in the next decade or two. The central disagreement is about the pace of the neuroscience research, which he argues will drag on in a linear fashion in spite of the fact that technological capability will continue to advance at an exponential pace.

He concludes the book with the following passage:

“In the end, however, thinking about the future of pleasure comes down to the individual. If pleasure is ubiquitous, what will happen to our human “superpower” of being able to associate pleasure with abstract ideas? Will it be washed away in a sea of background noise? If pleasure is everywhere, will uniquely human goals still exist? When pleasure is ubiquitous, what will we desire?

Conclusion

This has been a very brief and surface level summary of this book. I give it a strong recommendation (I think a copy can be picked up cheaply on ebay or abebooks, if not for free at the library), or from amazon. I think that it contains many positive and practical takeaways for the practitioner of Epicurean philosophy, or of pleasure/hedonic/utilitarian ethics in general.

David J. Linden, PhD, is a highly influential American professor of neuroscience at Johns Hopkins University and editor in chief of The Journal of Neurophysiology. He has written some popular books for the scientifically-interested lay audience, including in addition to this one, The Accidental Mind: How Brain Evolution Has Given Us Love, Memory, Dreams, and God and Touch: The Science of the Hand, Heart, and Mind.

This review summary was written by Friend Harmonious with editorial feedback from Guide Hiram.

Further Reading:

The Compass of Pleasure

He was loved by many in his community. One of his friends said: “He will be immortal to us“.

He was loved by many in his community. One of his friends said: “He will be immortal to us“.