Eikas cheers to everyone! Last Sunday, October 16th we had our first live-libation Eikas in Chicago. For years, the Society of Friends of Epicurus has hosted a virtual Eikas program, and this month was no different, except that I had the pleasure of being visited by Alan / Harmonious–one of our most active members, who many moons ago performed Lumen Inlustrans inspired by De rerum natura and whose most recent Eikas presentation was on Epicurean guidance of the soul. We enjoyed the virtual program, as well as lentil soup, cheese, crackers, salami, and wine.

In addition to the Eikas experience, the previous day we had a delightful Ethiopian restaurant experience and visited the beautiful grounds of the Bahá’í temple just north of Chicago. Although we have no affinity with the religion, the temple itself is an architectural marvel (there’s only one temple of its kind per continent) and the Gardens were lovely, and there we recorded In the Garden: An Interview with Hiram Crespo. It was a perfectly sunny day with no clouds, as you can tell from how shiny my bald-head was during the interview!

Since the Principal Doctrines enjoy ease of reference and are authoritative, they act as a type of social contract among us, and are a source of ongoing study, practice, and discussion. This month, Philosophy Break published Epicurus’s Principal Doctrines: 40 Aphorisms for Living Well. It continues Erik Anderson’s meleta about the Kyriai Doxai, which he organized into an eight-fold path based on the narrative he perceived in them. Anderson was the curator of a couple of webpages, including the Epicurean wiki. I had the pleasure of exchanging a few emails with him before he passed away a few years back. I’m thrilled to see this type of invitation and guide to study the Doxai with the aid of a recent philosophical ancestor like Anderson. It’s an invitation to profit from his wisdom, long after he’s gone. It honors his memory, and his original intention, since he clearly wanted others to benefit from his organized way of doing meleta.

Young was I once, I walked alone,

and bewildered seemed in the way;

then I found me another and rich I thought me,

for man is the joy of man.– Havamal, Stanza 47

Eikas and Epicurean Collective Memory

Every month on the weekend closest to the Twentieth, we celebrate Eikas. We offer a libation to the memory of our Hegemon, Epicurus of Samos, and another one to the memory of the first Epicurean Guide (Kathegemon), Metrodorus of Lampsacus. We then proceed to an educational program, where we continue the friendly conversations of Epicurus, Metrodorus, and their companions.

The tradition of Eikas predates Epicurus’ Final Will and Testament, where he mentioned “the rules now in force” concerning how to celebrate it. This means that the Hegemon and his friends started the tradition in memory of Metrodorus (who died first), and these traditions were likely influenced by the practices and values that were instilled on Epicurus by his mother (Chaerestrate), who had a keen interest in Greek folk healing and shamanism–which involved familial piety and ancestor reverence. Epicurus also honored the memory of his family members and his dear friend Polyaenus.

Two hundred years later, during the time of Philodemus of Gadara, we read in his scroll “On Piety” about Eikas as a sacrificial meal, and as a Festival of the Sacred Table. This makes me imagine that Eikas probably felt like a communion meal in the first century BCE. Today, Eikas is (usually) a virtual event that furnishes a chance for “meleta with others of like mind“, and it’s part of our toolkit for community-building.

Since October is a month that our culture dedicates to remembering our dead, in this essay, I’d like to evaluate some memorial aspects of the Eikas tradition in order to help us attain a deeper grounding on the theory and practice of Eikas. In my view, Eikas is the most essential Epicurean ceremony and the key to stabilizing and securing the continuity of our tradition, since we have observed that good Epicurean friends become a steady and helpful presence in each other’s lives through loyalty to the Eikas tradition.

Filial Piety Versus Blind Obedience

While there exists always some danger of excessive conservatism in ancestral reverence traditions, there are also benefits in the rootedness and grounding they offer.

Respect, love, and filial piety is not the same as tyranny of the old over the young, and does not imply blind obedience to elders. The Xiao Jing–the Chinese classic on filial piety, mentions that there should be “no ill will between superiors and inferiors“, and teaches: “Do not disgrace those who gave you birth“. Yet here, we find an embrace of tradition and strong social bonds, together with a rejection of blind obedience and the instruction to practice a form of parrhesia for the benefit of one’s elders described as “remonstrance” (defined as “a forcefully reproachful protest”):

Hence, since remonstrance is required in the case of unrighteous conduct, how can (simple) obedience to the orders of a father be accounted filial piety? – Xiao Jing

Epicurus’ Piety

The biographer Diogenes Laertius, in portion 10 of Book Ten of his “Lives of Eminent Philosophers“, cites Epicurus’ own character and filial piety (in the form of gratitude) towards Chaerestrate and Neocles:

… his gratitude to his parents, his generosity to his brothers, his gentleness to his servants … and in general, his benevolence to all mankind. His piety towards the gods and his affection for his country no words can describe.

Piety as a Technique

We can easily imagine how ancestral reverence traditions provide education, structure, and discipline to children and young people, and help to form their character, and also how “making our ancestors proud” may serve as an incentive for personal development, both in terms of our moral character and in terms of our achievements.

Since bodies of ancestors dissipate after death, they are not believed to intervene, therefore the theory behind Epicurean piety is not based on intervention from the spirit world. Filial piety techniques are meant to benefit the practitioners, not to reach the ancestral spirits.

The honor paid to a wise man is itself a great good for those who honor him. – Vatican Saying 32

The techniques of filial piety are much more efficient in forming the character if carried out with attention. In the Analects, Confucius argued that people should perform the sacrifices as if the ancestors were really there in the shrine, and similarly the ancient Epicureans used to say: “act as if Epicurus were watching“.

The object of piety should be someone worthy and wholesome, someone who was a helpful and loving presence in our lives. If their influence was degrading, piety is not due. In cases such as these, many ancestor reverence traditions incorporate therapeutic methods to help people work through these familial wounds.

The Libation as an Expression of Greek Piety

Having established the theoretical framework to consider Eikas in terms of filial piety, we’re also faced with the fact that Epicurean doctrines are at odds with much of what is traditionally associated with ancestor cults.

Philodemus, in his scroll Peri Thanatos (On Death), criticizes those who worry about whether a corpse was properly buried, and argued that it makes no distinction if one is unconscious in the water or under the ground. Ancient Greek tradition insisted that the dead had to be properly buried, but the Epicureans instead focused on the quality of the life lived, rather than the dignity of the corpse.

Ancestor reverence in Greece was tied to the Eleusinian mysteries and other mystery traditions and chthonic cults, where libations were poured for the dead in a consecrated pit dug into the ground. This is because the mysteries focused on nature deities, and the dead were believed to dwell underground. The members of the ancient Garden may or may not have strictly followed their culture’s filial piety traditions in this regard (perhaps they had an ancestral libation pit in their backyard, or perhaps not). Libations were offered using a phiale or patera (a consecrated ceramic or metal libation plate), and included milk, honey, wine and water.

After wine was poured from the phiale, the remainder of the oinochoē’s (wine jug) contents was drunk by the celebrant.

Since the social contract is a key concept in the Principal Doctrines of Epicurus, we must also consider the role of libations in sealing pacts. Libations were used for marking the act of entering into a covenant or social contract, or as a sign that one is fulfilling a pact previously made.

The Greek verb spéndō (σπένδω), “pour a libation”, also “conclude a pact” … spondaí marked the conclusion of hostilities, and is often thus used in the sense of “armistice, treaty.”

Nietzsche’s “New Fountains”

Attempts to create modern models of Epicurean community and practice remind me of a passage from Nietzsche’s Zarathustra where he discusses the reemergence of ancient ideas in “the fountains of the future”. He mentions that, after the death of God, new peoples would emerge.

He who hath grown wise concerning old origins, lo, he will at last seek after the fountains of the future and new origins.—O my brethren, not long will it be until new peoples shall arise and new fountains shall rush down into new depths. For the earthquake—it choketh up many wells, it causeth much languishing: but it bringeth also to light inner powers and secrets. The earthquake discloseth new fountains. In the earthquake of old peoples new fountains burst forth.

Thus Spake Zarathustra: A Book for All and None, Third Part, LVI. Old and New Tables, 25

I love this passage because our generation is seeing the emergence of many new peoples and new tribes. In addition to Epicurean communities, we are seeing Stoics, secular and religious Buddhists, every flavor of Paganism, and many other new sects and communities emerging in the post-Christian era. We can expect this trend to continue. I won’t dwell much on this so as to avoid going on a tangent, except to note that Nietzsche helps us to place the reemergence of EP within the context of the era in which we live, and that he does so with the use of poetry and art, which follows in the Lucretian tradition.

The Society of Epicurus Eikas

In our Koinonia, the libation is a mark of respect for tradition, and–for those of us who have made a formal resolution to practice Eikas–a mark of fulfillment of our word. But our virtual Eikas libation is of a secular variety, and our Libation is simply a toast in memory of Epicurus and Metrodorus, which pragmatically separates the initial period of informal introductions and conversations, from the time of discussion formally anchored in that month’s educational content.

But what is the utility of ceremony? There are several arguments. Confucian ceremoniousness is known as “Li“. According to that tradition, ceremony is used as a tool to impart harmony, stability, and order to social groups. The importance of ceremony was also accentuated by the Indianos in their Book of Community:

… That is why each community that wants to affirm its autonomy also has to face the creation of a ceremoniousness of its own … We not only need to tell the tale of what unites us, we need to represent it to feel like we are actors in the meaning of our lives.

As community we should be firm when faced with attitudes that strip away meaning, as this shows lack of self-respect.

The Taoists were not opposed to Li, but used to argue against excessive Li, since too much ceremony impedes naturalness (ziran). I believe this to be a legitimate criticism, which is why we only apply a minimal measure of ceremony at our Eikas.

A Word on Agreements and Oaths

Philodemus, in On Piety, says that Epicurus had strict rules concerning oaths (they must not be taken lightly, or in the name of trivial things). Oaths or agreements are a way to practice our Doctrines concerning justice. Organizing Eikas as a long-term tradition requires at least a small group of friends with the ability to collaborate effectively and fulfil their word. It’s considered unjust to break the agreements, except in cases where someone excuses themselves from Eikas via clear communication during a given month, with ample time for others to step in and carry the program that month.

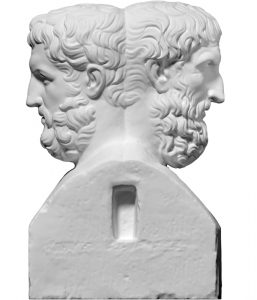

Many human values are practiced through Eikas, in addition to the recipes or foods we may enjoy, the educational value we get, and sculptures/crafts we employ–like the traditional Double-Bust of Epicurus-Metrodorus, sometimes called a “double herm”. Eikas is a way of instilling the value of responsibility in young adults. The prolepsis of responsibility is linked to the ability to respond, to the act of answering to others for something we’re responsible for. Practicing this value produces the great advantage of having trustworthy members of a social unit. It glues communities together and helps them to accomplish concrete projects through teamwork. In any circle of responsible adults, people have a right to expect that each member will abide by their word–if we are to take our Doxai seriously.

Many human values are practiced through Eikas, in addition to the recipes or foods we may enjoy, the educational value we get, and sculptures/crafts we employ–like the traditional Double-Bust of Epicurus-Metrodorus, sometimes called a “double herm”. Eikas is a way of instilling the value of responsibility in young adults. The prolepsis of responsibility is linked to the ability to respond, to the act of answering to others for something we’re responsible for. Practicing this value produces the great advantage of having trustworthy members of a social unit. It glues communities together and helps them to accomplish concrete projects through teamwork. In any circle of responsible adults, people have a right to expect that each member will abide by their word–if we are to take our Doxai seriously.

Eikas as Medicine for Rootlessness and Nihilism

One final note comes from some of the ideas concerning recruitment of new Epicureans found in the book The Sculpted Word. This book deals with art-critique, but also with theories and practices related to our methods of passive recruitment, since Epicurus was avidly against preaching in public.

The author of the book argued that during the Hellenistic Era, when Epicurus founded the Garden, many people were rootless cosmopolitans. Perhaps this is because many Barbarians had been captured in the conflicts and wars of the age, and were therefore foreigners living among the Greeks as slaves. Slaves made up a large proportion of the population of Athens. We know that slaves were allowed to study in the Garden. We also know that there were a few hetairai (sometimes compared to prostitutes, but many of whom were probably just free, single women) who frequented the Garden, and perhaps this is because the Garden attracted many men who were single, or alone and in search of association and amusement.

Epicurean philosophy values philia (friendship): through wholesome association, people who were rootless were able to set roots in a new community and feel grounded.

This reminds me of Afro-Diasporic religions whose founding elders instituted godparent-godchild relations and “houses” (known as ilé in Cuban Santeria, or terreiro in Brazilian Candomble) in order to create new ancestral lineages and preserve African communal order and cultural traditions in Cuba, Brazil, and other American countries. This helped the African slaves to deal with the trauma of enslavement, abuse, exploitation, displacement, and rootlessness once they were in the New World. I suppose a similar sense of “adopted family” is attained when people enter a Buddhist lineage, or a Sufi lineage. Many Hispanic immigrants in the US who convert to Santeria and create new communities are also healing rootlessness this way. In the Yoruba initiation system used by Santeros, one is “adopted” into a new ancestral lineage. This enabled African cultural systems to be more fully trans-planted in the Americas. The ilé (adopted religious House) becomes the adoptive family of the initiate. If the theory described in The Sculpted Word is correct, then ancient Epicurean Koinonias (communities) and Kepos (Gardens) functioned a bit like the ilés of Afro-diasporic faiths, building new connections and growing new roots.

Blacks in Cuba had been indoctrinated into the Catholic Church, and they had no choice but to respect it, even if it was a racially white religion that supported slavery. Hence, their insistence on having a parallel African alternative religious narrative based on Yoruba spirituality. Similarly, many of us today also question the moral authority of the institutions that we grew up respecting. The creation of an alternative social contract is a model that, in addition to affirming our true and authentic values, responds to a crisis in legitimacy–in this case, we often question the the values of Christianity and of our culture’s prevailing nihilistic consumerism.

The example of Afro-diasporic faiths makes me think of Eikas as a practice of adoption of new ancestors (in this case Epicurus, Metrodorus, and perhaps other Guides like Lucretius and Philodemus) in order to nurture new roots.

Conclusion

Filial piety promotes a certain amount of conservative ethos. This is neither good nor bad in itself, but it lends a certain stability to cultural practices, identities, and institutions. It’s possible that this stability is part of what Epicurus was trying to impart via his Eikas feast: a certain measure of being grounded in the midst of a rootless, restless, nihilistic society.

By adopting Epicurus and Metrodorus as philosophical “ancestors” when we celebrate Eikas, we slowly grow new roots in the Epicurean Gardens. Eikas is one of the ways in which philosophy becomes native to a new land and to a new soul. The Eikas feast makes philosophy tangible in our time and place, and provides a concrete vessel to practice Epicurean friendship, wisdom, culture and community.