The following essay is a continuation of our essay on PDs 24 and 28

Further Reading: Parable of the Hunter

It is not possible to live pleasantly without also living wisely and well and rightly, nor to live wisely and well and rightly without living pleasantly; and whoever lacks this cannot live pleasantly. – Principal Doctrine 5

The above Doctrine offers us a test to help us separate true Epicureans from other hedonists and from other philosophers.

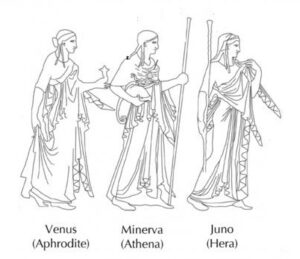

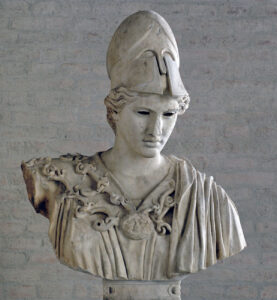

The words used are φρονίμως καὶ καλῶς καὶ δικαίως (phronimos kaj kalos kaj dikaios). Phronimos / phronesis is usually translated as Prudence, sometimes as practical wisdom. Kalos is sometimes translated as “well”, or as “noble”. Dikaios translates as “just”, sometimes as “right”. These ingredientes are all needed to live pleasantly according to Epicurean doctrine. For this reason, in order to encourage the memorization and paraphrase of this doctrine, I like to imagine this as the doctrine of the “Four Sisters” who must walk together with the true Epicurean: Iustitia (or any other personification of Justice), Prudentia (who could be personified by Athena / Minerva), Nobility, and Hedone (which I associate with Venus Urania, the patroness of the Garden). Imagining these “Four Sisters” “walking with” the genuine Epicurean is a way to memorize, visualize, or to imagine this Doctrine. In my attempts to create a visual of the Three of the Four Sisters, I was unable to find Minerva and Venus with Iustitia or Themis or Metis, but I found more than one depiction of them with Juno, so I used her instead. Upon thinking about this, Juno is perfect for this, as she is the goddess of marriage, which is one of the most universal types of contract.

Prudentia carries the preconception of “providentia” and of planning ahead of time, and therefore is needed for hedonic calculus. Minerva is an intellectual deity, and in fact her name shares semantic roots with the word “Mind”.

PD 5 clearly states that pleasure is not enough. This is due to the instructions in the Letter to Menoeceus to carry out hedonic calculus, which requires prudence (phronesis, or practical wisdom, which is required for living wisely) to help us discern which pleasures/pains to choose/avoid. That’s simple enough: we need Pleasure and Prudence, but why is Justice here?

The PD’s say A LOT more on Justice. For instance, in PD 17, we find the diagnosis of perturbation for the unrighteous. Righteous, law-abiding people who fulfil their terms of the social contract enjoy ataraxia (ὁ δίκαιος ἀταρακτότατος), but if people are unjust, they experience great perturbation or disquietude (ὁ δʼ ἄδικος πλείστης ταραχῆς γήμων). The key words here are ataraktotatos (which relates to tranquility, a-taraxia, the state of non-perturbation), and taraxes (perturbation). Here’s an instance where the PD’s emit a judgment that constitutes a diagnosis (a perturbation), that exposes a problem for treatment.

The just person enjoys the greatest peace of mind, while the unjust is full of the utmost disquietude. – Principal Doctrine 17

PD 17 and PD 5 taken together mean that these diseases of the soul (perturbations) tied to people’s unjust character must be treated and healed PRIOR TO being able to advance in philosophy.

One metaphor for how justice FEELS in one’s soul is the Kemetic (Ancient Egyptian) metaphor of the heart being weighed in the balance. If it’s lighter than a feather, then the dead may pass on to the afterlife. If the heart is too heavy, it does not pass. We do not believe in the afterlife, but this metaphor of light-heartedness as justice naturally appeals to any materialist. After all, weren’t the Epicureans known as “laughing philosophers”. Vatican Saying 41 makes it clear that laughter and light-heartedness is an Epicurean virtue, and the association of the feather of Ma’at (righteousness) with lightening up seems to indicate a relationship between justice and light-heartedness. Even Nietzsche said that if there IS a devil, it’s the “spirit of gravity”.

It is impossible for the person who secretly violates any article of the social compact to feel confident that he will remain undiscovered, even if he has already escaped ten thousand times; for right on to the end of his life he is never sure he will not be detected. – Principal Doctrine 35

Concerning Justice, we also find in PD 35 an appeal to a person’s sense of shame and apprehension at the possibility of being caught doing something that goes against the social contract. This doctrine could be called the “doctrine of the stigma”, because it discourages injustice based on an appeal to shame and fear of being detected, and based on the fear of the results of this. Another reason why we need PD 5 is that since the stigma of guilt is experienced as a perturbation, it keeps us from living blissful lives.

There are many scenarios that we can think about where either justice or prudence is lacking, and so the life of pleasure is not complete and can not be labeled Epicurean. These exercises of putting before our eyes various hypothetical scenarios, or thinking back to real ones we’ve encountered, may help to demonstrate what the founders were thinking about and discussing when they established Principal Doctrine 5.

The most common modern scenario for understanding PDs 5, 17, and 35, in my opinion, has to do with wage workers who fail to fulfil their side of the labor contract. Employers may experience this as fear of litigation, or of losing their best workers if they fail to uphold their side of the bargain. Working for wages is probably the most common type of contractarian relation in the modern world, one which most people get to experience at some point. We can imagine a worker who fails to perform his contractual duties, or is always late for work, or somehow does not deliver the services or goods he is bound to produce, or breaks important rules concerning harassment or other ethics rules of their job. If a person does this, they will be worried about losing their job. If they do not enjoy self-sufficiency, this worry may consume them. If they are self-sufficient and their job is only a source of extra income, the perturbation from their sense of guilt will be minor. So what this PD is saying is that an Epicurean must have Justice on his side, that he must avoid having to constantly worry about being caught breaking the terms of a covenant. He does this by fulfilling its terms, as he will not be able to live pleasantly if he constantly worries about possibly losing his job.

Of course, the other side of PD 17 is that the righteous experience ataraxia. Thanks to their innocence, they get to enjoy the pleasure of their sense of decency and peace of mind. This wholesome, healthy state is a positive value that most people who are just probably take for granted. If a worker or employer goes above and beyond their call of duty based on their contractual terms with each other, and learns to love the virtue of responsibility and hard work, they will experience a pleasant, edifying sense of pride, of decency, and of good character. Those of us who are immersed in wage slavery know too well the “Friday night” feeling, the sense of accomplishment and entitlement that comes with being a good worker.

Why else might Justice be a requirement for the Epicurean life, according to PD 5? One possible additional hypothesis is that this may have been a way for the founders to protect disciples from unwholesome association: if someone is incapable of fulfilling their part of the social contract, or of abiding by the law, then their not “walking with Justice” is supposed to exclude them from being seen as properly Epicurean. They will need to work on that prior to advancing in philosophy, and other Epicureans will appropriately be wary of the extent of their association with someone who is likely to break the terms of the social contract.

For this reason, I call PD 35 the “doctrine of the stigma”: it not only warns the perpetrator of the perturbations related to breaking oaths and being a social delinquent. It also warns the Epicurean friends (for whom the PD’s were authored) to be mindful of associating with oath-breakers. For this reason, I believe that PD 35 is a precursor to PD 39.

Further Reading: