As I read Michel Onfray’s La sculpture de soi (The Sculpture of Oneself), a book on ethics and aesthetics, I’ve been pondering the role of Our Lady Aphrodite in the life of an Epicurean philosopher. We philosophers are said to worship in the altar of Athena, the Lady of wisdom and civilization, and this must always be true. But Epicurus teaches that nature–not reason–is our principal Guide, and pleasure/pain is considered a valuable faculty granted to us by nature. The archetypal embodiment of pleasure is Venus / Aphrodite, not Minerva / Athena.

We are seekers of pleasure (and, ergo, of Venus) as the highest good. There is a feminine and aesthetic sensibility to Epicurean spirituality which must be acknowledged. We have also had the fortune of sharing with Venus the same insults, the same stereotypes and defamation that She has faced throughout history from the same groups of people. We Epicureans are, in a manner of speaking, the people of Aphrodite. Hence I felt the need to write this piece and address her mythology, her semantics, her imagery, and the layers of meaning that She imposes upon reality because, inevitably, our cosmos is painted in her hues. She IS Mother Nature.

Rather than the hallowed land of Ancient Athens, that beacon of civilization, we look to the island of Cyprus as our spiritual center, where Aphrodite is said to have been born inside a shell out of the foam of the seas. In this manner, Epicureanism reveals itself to be a heresy, a heterodoxy within philosophy. We declared our independence from orthodoxy in the same way that Moslems did when they decided to face Mecca in prayer, rather than the traditional Jerusalem. They had become a separate people … and so did we when we chose Pleasure –not Reason, as the Platonists did– as the highest good. We had emancipated ourselves from the Athenian establishment.

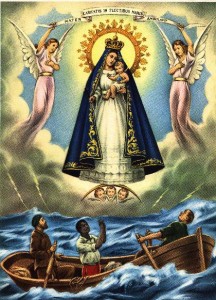

There is, however, another spiritual center for our patroness. One in the New World: the holy city of Cobre in Cuba, where pilgrims visit her great cathedral daily with gifts of oranges, candles, honey and yellow flowers. It’s the spiritual center of the patroness of Cuba, la Señora de la Caridad de Cobre (Our Lady of Charity of Copper/City-of-Cobre), who is syncretised with the Lukumi Goddess of Love, Ochun, and clad in the aesthetics of what in the Spanish-speaking world is known as negritud. She is the Black Aphrodite, the Goddess of rivers, of the arts and creativity, of femininity, and of sex.

Both of her spiritual centers, Cyprus and Cobre, are named after the copper mines that they’re known for … a curious and random fact considering the vastness of the Earth’s geography. When used in batteries, copper has a negative/receptive electric charge which, again, is reminiscent of the Goddess’ femininity and overt, liberated sexuality.

Archetypes resemble the beds of rivers: dried up because the water has deserted them, though it may return at any time. An archetype is something like an old watercourse along which the water of life flowed for a time, digging a deep channel for itself. The longer it flowed the deeper the channel, and the more likely it is that sooner or later the water will return. – Carl Jung, Father of Modern Psychotherapy

A word must be said of the aesthetics of a wisdom tradition and how wisdom can be passed down, not always in the form of teachings and proverbs, but in the form of art, music, oral folklore, and imagery. This is particularly the case in oral cultures where writing has not developed or is marginal. Take Cupid, whose arrows carry both the poison and the remedy: what better metaphor for falling in love can there be? Does this not mirror Epicurus’ sage advise that we are lucky if we are not hurt by lust? Through philosophically-inspired art, imagery can carry a thousand words, it can teach, edify and fortify the soul in addition to the ecstasy and rapture that a song, piece of literature, or image can evoke.

From the name of Venus we derive the name for venereal diseases. Sexually transmited diseases are also the gifts of Venus. She is said to be the one whose mission it is to sweeten the world, to make life worth living, but She also brings bitterness. One principle can not exist without the other. We need both pleasure and pain to be able to identify the good and the bad in this world.

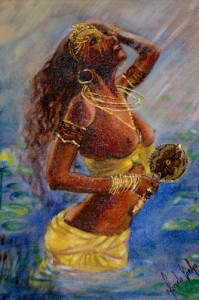

There is more to Oshun, the Goddess of the sweet waters of the rivers. Just as the waters provide, when calm, a clear (or agitated) mirror that we can find ourselves in, so She rules mirrors, and self-conception. One Oshun-worshiper once told me: “whenever you are confused, just talk to the mirror. Because the mirror don’t lie: whether you are sad, confused, tired, whatever, the mirror always tells the truth. Let it all out and talk to the mirror. The mirror don’t lie!”. This was true in the days of Snow White. It’s still true today.

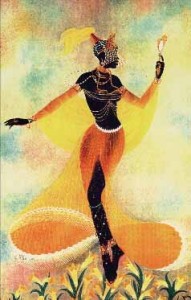

Also sacred to her are fans. Perhaps this is because She is a water Goddess and manual fans look like shells from the ocean. Or perhaps fans have to do with being a Queen, being fanned and given comfort and pleasure.

Her color is golden, the color of copper and of honey, which is also sacred to Her as She is said to sweeten life.

Being the embodiment of the Pleasure principle, one of her roles in the traditional stories told about Oshun has to do with sweetening and appeasing the other Gods when they lose their heads. As archetypal personality types, the Gods (Orisha) in the Afro-diasporic Santeria tradition do have their idiosyncrasies and some are conceived as hot-headed. It is said that, in order to bring Ogun (the God of iron and of smith-work) back out of the forest and into civilization so that there could be laboriousness again, Oshun once smeared herself in honey and danced naked for him, enchanting him and luring him back into the city.

Ogun, naturally, fell madly in love with Her. Who wouldn’t? She’s the Goddess of beauty! In the Santeria cosmos, Oshun eventually married Ogun but was unfaithful and left him to go with Shango (God of thunder). This legend is reminiscent of another one from the Greek pantheon about the great embarrassment that the God Hephaistos experienced when he found his wife Aphrodite in bed with Ares and, when he told the Gods, they merely laughed at him.

The parallels between these three deities in both pantheons are many. If understood as psychological prototypes, we can see that the deformed Hephaistos was rejected by Hera and Ogun was similarly rejected by his mother Yemaya for other reasons: he was a rapist. Because of his crime, Ogun (the God of iron and smith-work) was condemned to forever labor on behalf of human civilization and it is believed that he brings the ever-expanding gifts of technology and invention to humankind. Motherly rejection, and a wife’s infidelity and humiliation, are scars shared by both the African and Greek Divine Mechanics. In both cases, the introverted, rejected God sublimates his pain and transforms it into utilitarian creativity and beauty in his workshop.

As for the War-Gods Ares and Shango, both were womanizers and, as symbols of male aggression, were found irresistible by the prototype of the sexual female. The sexual escapades of Aphrodite and Ares were as much the stuff of gossip among ancient Greeks as the ones concerning Oshun and Shango are among Cuban Santeros today. We all know women are from Venus and men are from Mars. Our female ancestors found aggression sexually arousing because it meant that, as a partner, an aggressive warrior would be able to defend her and protect her, and an aggressive hunter would be able to feed and clothe her and her offspring: hence nature placed pleasure in their instincts with regards to these aggressive qualities.

In addition to carrying within it a wisdom tradition, and perhaps a series of mysteries or ineffable truths that cannot be put into words, there is a therapeutic quality to the imagery and narratives that adorn many Gods. These images carry both collective and personal therapeutic value for the worshipers.

Our Lady of Charity is considered to be a mulatto Goddess by Cubans. She embodies both the African and Spanish faces of the Cuban experience and identity and she synthesizes them into one image, blending the tensions that underlie the history of exploitation and slavery between the two races and resolving them through art, music, aesthetics, vibrant culture, and even ecstasy. Just as Tonantzin/Our Lady of Guadalupe did for the Aztecs/Mexicans under Spanish rule, Oshun/Our Lady of Caridad gave the Cubans a celebrated identity symbol.

I would argue that this plays a hugely important role historically. Few images are as powerful and precious to the people that claim them as the images of these modern Goddesses. Any visit to Mexico or Cuba, or immersion in these two cultures, would make this clear. Even if these are nominally Catholic cults, the deeper layers of meaning, identity and imagery are recognized by all and quench a profound spiritual thirst in the people that claim them.

Mothers cry to these images when they are suffering because of their husbands, children, or families because they feel that only their Lady could understand their tears, and feel a sense of intimacy and identification with the divine womanhood, motherhood, and femininity of their Lady. Personifying these abstract concepts makes them tangible, relateable. Is this not what philosophical materialism seeks to do with all spirituality–to make it tangible, bring it down to Earth? If our epistemology teaches that reality is experienced directly through the senses, must our Gods not also be sensually available through all the art-forms?

But the aesthetics and the ethics of the cult of Aphrodite are all incidental. Ultimately, we are Epicureans who do as pleases us: in our tradition, Aphrodite is sought for the mere pleasure one derives from the act of contemplating her perfection and ataraxia. If we ever lose sight of this, we have stopped being Epicureans. When we place our eyes upon divine imagery, it is only to feed the soul by taking in the nectar of the Gods’ ataraxia.

Further Reading: