“Rhetoricians might flatter flies with honey,

but politicians feed flies bullshit.”

WE GOT BEEF

A DISEMBOWELMENT OF THE DIALECTIC,

POLITICS, AND OTHER ORGANS OF BULLSHIT

I have a bone to pick with rhetoric.

Here’s the heart of the issue: talk is cheap. People chew fat in political chats without purpose — no learning occurs, no truth is shared, no friendship is found. Everyone misses the meat of the matter. Opinions are skin-deep. Debate rarely disembowels delusion. Too often, rhetoricians and orators enlist themselves in the service of manipulation. After all, “the end of rhetoric is to persuade in a speech” and not to validate truth with evidence (Philódēmos, On Rhetoric, I, col. 3). Their art does not “depend on arguments from physical facts” because “their art is a power of persuasion” (Ibid., II, 12, col. XIX). For instance, it is agreeable to suppose that honey attracts more flies than vinegar — true, but as a student of nature and pupil of the Garden (so guided to treat politics with suspicion), I observe that nothing attracts so many flies as bullshit.

Those who study in the rhetorical schools are deceived. They are charmed by the tricks of style, and pay no attention to the thought, believing that if they can learn to speak in this style they will succeed in the assembly and court of law. But when they find that this style is wholly unfitted for practical speaking they realize that they have lost their money.

(Epíkouros, Against the Rhetoricians)

The rhetorical τέχνη (tékhnē, “technique”) of the sophists provides a technical method without practical application; at the same time many practical orators enjoy success, and wield influence without technically possessing any teachable skills, having mastered neither art nor science. Dialecticians may enjoy sagacious reputations, but may also lack receptivity, perspective, and may provide people with impractical, ineffective advice. Both educated rhetoricians and natural orators present dangers as agents of persuasion — dialecticians turn the practical benefits of philosophy into abstractions; rhetors misuse the art of prose for manipulation; orators’ aptitude for practical persuasion lacks a foundation in natural ethics.

Each of the rhetorical arts and practices fails to ground themselves in nature. As human agents of manipulation, professional persuaders fail to refer to the natural “goal” of “living blessedly” (Laértios 10.128). Each of these tools can be appropriated to service a political agenda. Only the true philosophy provides students with the tools they need to understand reality and pursue happiness. To quote the lead character from a favorite, adult cartoon, “Everyone wants people they like to be right. That’s why popular people are fucking dumb” (Rick and Morty, Season 3, Episode 4). As Epíkouros teaches, “the purest security is possible by means of the peace and the withdrawal from the masses”, never by chasing their satisfaction (Key Doctrine 14).

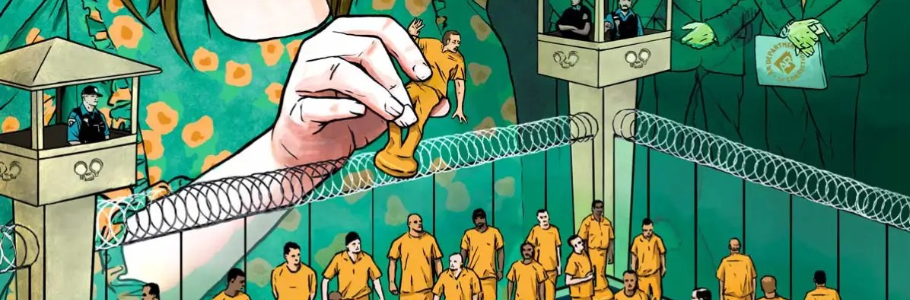

Modified from artwork by Kasten Searles for “The Queen’s Gambit” from the Arkansas Times, March 2024

THE PRISON OF POLITICS

Unlike other schools, the Garden rejects politics as a valid field of inquiry and remonstrates the rhetorical tools that support the political ambitions of professional persuaders. As φιλοσοφία (philosophía) is the “love of wisdom”, so politics is antithetical to friendship and wisdom. While Epíkouros does not dismiss civic engagement, he warns against pursuing a political career. Such a pursuit requires either subservience to wealthy interests, or else, submission to popular opinion, or engagement with senseless gossip. The most effective politicians are not those who are the most educated, for “some come out of the schools worse than when they went in” (On Rhetoric, I, 35, 1 ff.=Suppl. 19.13 ff.), but those who are best at “studying what pleases the crowd and practicing” (Ibid., I, 45, 13 ff.=Suppl. 23, 20 ff.) In this way, through pleasing speech, an otherwise unskilled narcissist “can become skilled in politics” (Ibid.).

Political narratives, in particular, are uniquely dubious. Self-promoting orators spoil healthy discourse by drawing people into pointless debates. Rhetoricians excel at erecting scarecrows. Argumentative puppets present themselves as prime cuts of intelligence, yet many are without substance. Popular speakers are incentivized to sell unpalatable policies for the sake of their own enrichment. Politicians dress the inedible entrails they cook with zest. They spice lies to hide their rancid flavor. They sew empty arguments from skin and bones. Debates are dressed for taste, and, as mentioned, rarely dissect the meat of the matter. Dialectical discourse is dangerous. Rhetoric and oratory are ineffective at verifying true statements and, more importantly, impractical at cultivating friendships. As Philódēmos acknowledges, “Politics is the worst foe of friendship; for it generates envy, ambition and discord.” (On Rhetoric, II, 158, fr. XIX).

In speaking of a “free life”, Epíkouros affirms that it

is not possible to be acquired by a lot of money [made] through an unscrupulous means [nor] is without servility to the mob or authority, rather [it] acquires everything [it needs] in continuous abundance; nevertheless if [one did procure] any money by chance, then the latter can be easily distributed to those nearby for goodwill. (Vatican Saying 58)

In this essay, I mean to review rhetoric, dissect dialectic, purge politics, and oust the aura of oratory. We will skim the fat from inference by demonstrating the dangers of logical induction. As Epíkouros teaches, we “must liberate ourselves, out of the prison [built] upon circular” proceedings, social programming, indoctrination, senseless gossip, “political” affairs”, and other practices that sacrifice the testimony of the senses for persuasive story-telling (Vatican Saying 58). “If you contest every single one of the sense perceptions, you can neither judge the outward appearance nor can you affirm which of the sensations you, yourself say are deceptive according to the way in which the criterion operates” (Key Doctrine 23).

UNFOUNDED INFERENCE

Epicureans reject both philosophical “reasonings in the form of Aristotelian syllogisms or inductions” as well as “other dialectical procedure(s)” (On Irrational Contempt 2). As Polýstratos writes, those persuaded by such procedures “are fools who construct their argument solely on the basis of the conviction of others” and not through empirical investigation (Ibid.). “[B]y the dialectical means mentioned, one cannot deliver the soul from fear and anxious suspicion” because the conclusions of the rhetor, the orator, and the dialectician are not founded on physics (Ibid.). The dialectic is rejected “for want of qualification” as a reliable criterion of knowledge, for the Epicureans “suppose the study of nature provides the proper space for the voices of the facts” (Laértios 10.31). The only valid testimony is from the senses — speculation, hearsay, assumption, induction, and conjecture are inferior practices to the process of confirming hypotheses with evidence. “We shall say that the one who infers thus fails because he has not gone through all appearances well, and indeed that he is corrected by the appearances themselves” of real things (On Signs). When “divorced [from] the real phenomena”, then reality gets “cast out of the whole study of nature and then flows from a myth” (Laértios 10.87).

By contrast, Epicureans employ “the method of analogy”, observing nature, inferring hypotheses, and substantiating with evidence. “For there is no other correct method of inference besides this” (Philódēmos, On Signs). Sophistic rhetoric further confounds the process of substantiating hypotheses with observation. By contrast, evidence justifies the demonstrable truth of statements. Otherwise, flawed methods lead to self-defeating conclusions. “For the arguments that they devise to refute the [Epicurean] method of analogy contribute to its confirmation. […] It is the same in other cases, so that as a result they refute themselves.” (Ibid.). As pertains to professional persuaders, rarely are politicians and scientists the same people.

DIABOLECTICIANS

Unlike other philosophers, Epíkouros does not recognize the dialectic as a distinct branch of philosophy (Laértios 7.41). Rather, he recognizes the dialectic as a mere method, which, by itself, cannot arrive at the “truth” it seeks to find. Speaking of the Epicurean Garden, Diogénēs reports that “she has withdrawn the Dialectic [and] rejects it for want of qualification;” for the Epicureans “suppose the [study of] natural [phenomena] provides [the proper] space for the voices of the facts.” (Ibid., 10.31). Epíkouros called “the Dialecticians totally toxic” (Ibid., 10.8) and later refers to “dialectic” as being “pretentious” (Epistle to Hēródotos 10.72). Contemporaneously, “Metródōros wrote […] Against the Dialecticians” (Laértios 10.24). He was documented “ridiculing those who consider the dialectic method more accurate” (On Rhetoric, II, 45, col. XLV). Philódēmos positively identifies the position of “the dialectician” as “a position which we refute” (Ibid., I, 190, col. IX; I, 191, col. X). Polýstratos writes that dialectical reasoning is based purely upon the false premises of dialectician’s “own conviction” (On Irrational Contempt 2). Instead, “one must, for the sake of oneself” observe nature to determine the truth of statements (Epistle to Hēródotos 10.72). Otherwise, as Philódēmos notes, “those who use dialectical reasoning do not know that they are shamefully refuting themselves” (On Signs).

For a demonstration of the dialectic in action, consider the following exampe, courtesy of the American, two-party political system: Suppose the Pink Team asserts that ‘An asteroid is coming! We need funds to stop it!’ The Yellow Team responds: ‘There is no asteroid. You just want money.’ Fortunately, everyone is a respectable, patient, educated dialectician, and everyone agrees to the wise rules of their admirable methodology. They proudly reach a compromise: ‘After extensive consideration, we have determined that there is a chance that an object, perhaps, in this case, an asteroid, of indeterminate size, mind you, may enter a region of spa —’

SLAM. That was the sound of nature crushing their dialectic.

THE RACKET OF RHETORIC

“[T]o practice rhetoric is toilsome to body and soul, and we would not endure it. [Rhetoric] is most unsuitable for one who aims at quiet happiness, and compels one to meddle more or less with affairs, and provides no more right opinion or acquaintance with nature than one’s ordinary style of speaking, and draw the attention of young men from philosophy”

(Philódēmos, On Rhetoric, II, 52, col. 38., II, 53, col. L).

Rhetoric is a technique, an art of prose. Therein, Epicureans “do not claim that rhetoric is bad in itself” (Ibid., II, 142, fr. XIII). Simply, that rhetoricians “are like pilots, who have a good training but may be bad men.” Rhetoric is a weapon that any trained person can learn to wield. Even “the perfect orator” need not “be also a good man and a good citizen” as “in the case of any other art;” for example “a good musician may be a villain” (Ibid., II, 127, fr. XIII=II, 75, fr. XIII.). The 19th-century, French author Flaubert cautions, “Il ne faut pas toucher aux idoles: la dorure en reste aux mains” or “You shouldn’t touch idols: a little gold always rubs off” (Madame Bovary 3.5) — we receive this phrase as “never meet your heroes“. Indeed, were “the greatest rhetors [to] accomplish all they wish […] then they would be tyrants.” (On Rhetoric, II, 151, fr. VIII).

“To tell the truth,” so writes Philódēmos, “the rhetors do a great deal of harm to many people”, by defending the art of manipulation (Ibid., II, 133, fr. IV). He documents that rhetoricians “were not in good repute at the very beginning” as far as “in Egypt and Rhodes and Italy” (Ibid., II, 105, fr. XII). Hermarkhos claims that “rhetors [do not] deserve admiration”. “Moreover the rhetors charge for the help they give, and so cannot be considered benefactors” (Ibid., II, 159, fr. XX). By contrast, “the philosophers give their instruction without cost” (Ibid.). “Metrodorus teaches in regard to rhetoric that it does not arise from a study of science” (Ibid., II, 193, fr. 2). “The end of rhetoric is to persuade in a speech”, designed to disregard nature as is convenient. “It is clearly proven that the art of the rhetor is of no assistance for a life of happiness” (Ibid., I, 250, XVIII).

STUPID SOPHISTS

If he knew that he could not […] become a philosopher […] he might propose to teach grammar, music, or tactics. For we can find no reason why anyone with the last spark of nobility in his nature should become a sophist…” (Ibid., II, 54, col. 39., col, LI).

The Epicurean critique against rhetoric is dually applied to and principally exhibited by a method that they refer to as sophistic (also referred to as “panegyric” or “epideictic” rhetoric). In general, people “are led astray by sophists and pay them money merely to get the reputation for political ability” (Ibid., II, 46, col. 33). It has been grossly easy for rich orators to persuade poor laborers to fund their schemes. Philódēmos observes that “sophistical training does not prevent faulty speech” (Ibid., I.182, col. I—I, 186, col. V). In fact, “some do not care at all for what they say” so long as it accomplishes their rhetorical goal, regardless of the greater goal of life (Ibid., I, 244. col XIII). “And when they do praise a good man they praise him for qualities considered good by the crowd, and not truly good qualities” (Ibid., I, 216 col. XXXVa, 14).

“[I]t follows that”, as is the case with other forms of technical rhetoric “those who possess this ability [of sophistic rhetoric] have acquired it without the help of scientific principles” (Ibid., I, 136, 20=Suppl. 61, 19). “[R]hetorical sophists” are known “for wasting their time on investigation of useless subjects, such as […] the interpretation of obscure passages in the poets”, as when civic policy is guided by mythic texts (Ibid., I, 78, 19 ff.=Suppl. 39, 5 ff). Compared against the philosophers, “the instruction given by the sophists is not only stupid but shameless, and lacking in refinement and reason” since it does not take into account the goal of life, nor commit to a devoted study of nature (Ibid., I, 223, fr. III). Instead, sophistic rhetoric appeals to authority and tradition by means of equivocation, obfuscation, and exploitation of ignorance.

CULTIVATING IGNORANCE

Often, obfuscation “is intentional”, as is the case “when one has nothing to say, and conceals the poverty of his thought by obscure language that he may seem to say something useful” as with equivocation (Ibid., I, 156, col. XIII). Other times, we observe “unintentional obscurity [that] arises from not mastering the subject, or not observing the proper formation […] and in general from failure” (Ibid., I, 158, col. XVI). Obscurity in discourse also arises “from ignorance of the proper meanings of words, their connotation, and the principles on which one word is to be preferred to another” (Ibid., I. 159, col. XVII). In these cases, the success of an orator corresponds not with knowledge, nor coherence, but with a practical ability to persuade a mob. “Most, if not all [of] the arguments do not prove what they claim to prove even if the premises be granted.” (Ibid., I, col. 5). “The worst class of arguments are those which act as boomerangs and demolish the position of the disputant” (Ibid. I, 4, col. I=Suppl. 4, 17).

For example, suppose that a sophist means to convince a legislative body to support a piece of legislation, but they lack meaningful substance. It behooves them to appeal to their audience’s preferences — moderates appreciate an appeal to custom (e.g. it’s the way it is); traditionalists appreciate an appeal to myth (e.g. it’s the way it’s always been); legalists appreciate an appeal to authority (e.g. it’s the law); populists appreciate an appeal to popularity (e.g. it’s what we want); economists appreciate an appeal to wealth (e.g. it’s profitable); bleeding-hearts appreciate an appeal to empathy (e.g. have a heart); ignorant people appreciate an appeal to simplicity (e.g. they’re trying to confuse you). The most ignorant are the most gullible, easy prey for skilled sophists. (Intentional obfuscation is masterfully exemplified by the “Chewbacca Defense” from the October 7, 1998 episode of South Park. The “Chewbacca Defense” leads to an irrelevant conclusion based on non-sequitur speech and a red herring.)

EMPTY ORATORY

Philódēmos spends the better part of On Rhetoric distinguishing rhetoric as a technical art versus legislative and judicial oratory, which he identifies as a practical skill. He writes:

The practical skill acquired by observation is not called an art by the Greeks except that sometimes in a loose use of language people call a clever woodchopper an artist. If we call observation and practice art we should include under the term all human activity.

(Ibid., I, 57, 23 ff.=Suppl. 29, 15 ff.)

There is a “division between the different parts of rhetoric (i. e. sophistic and practical rhetoric) which was made by Epicurus and his immediate successors (Ibid., I, 49, 14 ff.=Suppl. 25, 15 ff.). Unlike sophistic, Philódēmos suggests that one “could find reason for pursuing practical rhetoric”, even though this form of oratory does not qualify as a formal art (Ibid., II, 54, 41). Unlike sophistic methods of argumentation, practical oration (the ambassadorial oratory of diplomats, the deliberative oratory or legislators, the forensic oratory of lawyers) provides practical utility: “thousands of [Greeks] have been useful ambassadors, were prudent in their advice, were not the cause of disaster, did not speak with an eye to gain, and were not convicted of malfeasance in office.” (Ibid., II, 224, col. XIX). In these cases, “some do succeed by means of natural ability and experience without the aid of rhetoric” (Ibid., I, 47, I ff.=Suppl. 24, 10 ff.). They are less concerned with trying “to classify and describe metaphors” instead of trying to give “practical working instructions” (Ibid., I, 171, 2, col. XII).

Still, even without methodical manipulation, oratory does not guarantee happiness, and provides no moral direction. It allows fools without skill to run offices that benefit from skill. Popularity insulates celebrities from the consequences of their actions. Oratory is the favored tool of talentless politicians whose only object is the advancement of destructive pursuits.

By contrast against the empty promises, unhelpful eloquence, and practical lies of orators, Philódēmos argues for παρρησία (parrēsía, “frank” or “free speech”), explaining that it is truly καλή φράσις (kalḗ phrásis), “lovely phrasing” or “beautiful speech” (On Rhetoric, I, 149 IV). Epíkouros commits to using “ordinary expressions appropriately, and not express oneself inaccurately nor vaguely, nor use expressions with double meaning” (Ibid., I,161, Col XIX). Ornate oratory might promote popularity, but rarely does it reduce anxiety.

POLITICAL PROGRAMMING

Rhetoricians might flatter flies with honey, but politicians feed flies bullshit.

Epicurus believed that there was no art of persuading large bodies of men; that those who are not rhetoricians sometimes are more persuasive than the rhetoricians; that those trained in panegyric are less able to face the tumult of the assembly than those who have no rhetorical training; that Epicurus spoke of arts, and said that those acquainted with them were benefited, but did not mean that this enabled them to attain the end; if anyone possesses the power of persuasion it is responsible for evil and not for good.

(On Rhetoric, I, 99, 5b=Suppl. 48, 15)

While the arts of persuasion are discouraged, even then, Epicureans evaluate the dialectic and rhetoric above political discourse. “[W]e declare [politics not] to be an art “ (Ibid., Section II-a). Politicians are famously dishonest because “a clever man without studying the technical works of the sophists can study some sophist’s speech and so learn to imitate them.” (Ibid., I, 130. col. XXIX). Command does not require comprehension. “They certainly leave no place for any science…” (Ibid., I, 49, 14 ff.=Suppl. 25, 15 ff.). Indeed, “Delivery depends, too, on natural endowment, beauty of voice, grace of body” (Ibid., Col. XV). The job of “the statesman” is only to “discover the inherent political arguments” corresponding to “what appears true to the crowd” and then to manipulate them to the best of their ability (On Rhetoric, I, 209. col. XXVIII). As conditions change, one politician can advance murderous schemes, while another need to only wear the wrong-colored outfit to incite widespread, public ridicule. “There is no method by which one can” reliably “persuade the multitude, either always or in the majority of cases”, so pursuing politics is akin to delaying your own happiness (Ibid., II, 120, fr. XIX). Usually, success in politics requires either “a lot of money made through unscrupulous means” or “servility to the mob or authority” (Vatican Saying 67). Neither of those conditions are conducive to happiness.

To sum up; by no means should the philosopher acquire political experience, or rhetoric of that sort. It is evident that it is the height of folly to say that a study of nature produces a ἕξις [“habit”] of political oratory, especially since they introduce into the scheme of philosophy example andenthymeme” (On Rhetoric, II, 35, col. 38).

Philódēmos identifies those arguments that appeal to prejudice, traditional paradigms, historical precedence, and common belief as being “vain” (Ibid., I, 286, col. VII). They are “mere padding [to] provoke applause”, all “because the multitude is foolish” (Ibid., II, 39, col. XLI, I. 14). It is equally foolish that those “in political speeches use syllogism and induction which the dialecticians pride themselves on using” (Ibid., I, 286, col. VII). Therefore:

“[The wise] will [not] meddle in politics […] nor will they tyrannize; nor will they bark like a Cynic, […] and they will serve jury duty, and they will leave behind writings, but will not make public endorsements, and they will take precautions for their possessions” (Laertios 10.119).

THE HARBOR OF PHILOSOPHY

“But this does not apply any more to philosophy”, nor does it apply to “the Epicureans who refrain from such things” (Ibid., II, 144, fr. II). “Philosophy is more profitable than epideictic rhetoric, especially if one practices rhetoric in the fashion of the sophists (Ibid., I, 225, fr. I). “To tell the truth”, so Philódēmos boasts, “philosophers gain the friendship of public men by helping them out of their troubles.” (Ibid., II, 133, fr. IV). He explains, “they live in peace and justice and tried friendship; those whom they find opposed to them they quickly soften” (Ibid., II, 160, XXI-XXV. II, 162, fr. XXVII). As mentioned, the Epicureans pride themselves on παρρησία (parrēsía, “free speech”). “In speaking one should not resort to ignoble rhetorical tricks, these have less effect than a straight-forward character” (Ibid., II, 126, fr. VI). Since the public tends to prefer comfortable lies, “it is better not to receive public preferment” (Ibid., II, 154, fr. XII.). Philosophers “help their country” not by patronizing the public, but “by teaching the young […] to act justly even if there are no laws, and to shun injustice as they would fire.” (Ibid., II, 154, fr. XIII.).

The primary resource that preserves the Epicurean deconstruction of oratory comes from Philódēmos in his book On Rhetoric. In this book, Philódēmos distinguishes technical rhetoric from practical oratory. He provides a critique of political speech and reviews the dialectic against the Epicureans’ method by analogy that anticipates the modern, scientific method.

Of chief concern, Philódēmos contrasts arts (like dialectic and rhetoric) against practical oratory and political speech, which are not teachable arts. “An art”, he writes “cannot be attained by one who has not studied it, and doing this regularly and certainly and not by conjecture.” He further explains that “this definition applies both to […] grammar and music”. He later adds “architecture, ship-carpentry, navigation, painting”, which all “had methods in olden time” (Ibid., I, 137, col. 33I.21). He concludes, “On the basis of this definition we declare sophistic to be an art” (Ibid., Section II-a). Here again, “That statement ‘He is a good rhetor’ simply means that he is experienced and skilled in speaking”, not that he is a good person. “For as we say ‘good rhetor’ we say ‘good artist’ meaning ‘skillful’” (Ibid., II, 234, col. XXXV).

VARIETIES OF DISCOURSE

“One cannot even say that all rhetors adopt one style”, since orators alter their deliveries to suit the disposition of their audience (Ibid., I.152, Col. VIII). In On Rhetoric, our friend Philódēmos provides an overview of the various types of rhetoric and oratory, in addition to reviewing the positions of the Peripatetics and Stoics. In The Art of Rhetoric, Aristotélēs distinguishes rhetoric by three domains of persuasion: [I] deliberative or symbouleutic (e.g legislative), [II] forensic (e.g. judicial), and [III] epideictic (e.g. charismatic speeches) types (Technē Rhētorikē). A later Peripatetic adds [IV] enteuctic (e.g. ingratiation) as a fourth category. Conversely, the Stoics refer to epideictic rhetoric as [V] enconmiastic (e.g. eulogistic). Philódēmos also identifies [VI] ambassadorial (e.g. diplomatic) oratory and [VII] eristic (e.g. controversial). While ambassadorial, deliberative, and forensic styles of oratory exemplify practical oratory, the precision of rhetoric qualifies it as a technical art. Unlike practical oratory, technical rhetoric is exemplified by epideictic, rhetoric, also called [VII] panegyric (e.g. pageantic) and/or [VII] sophistic (e.g. deceptive).

As regards dialectic, Philódēmos offers professional respect (especially when compared against the profession of politics, the practice of oratory, and the art of rhetoric). He elaborates:

For the method of question and answer is necessary not only in philosophy and education, but often in the ordinary intercourse of life. The method of joint inquiry frequently demands this style. Moreover this method is adopted by the rhetor in the assembly as well as in the court of justice. (On Rhetoric, I, 241, col. XI).

While Philódēmos rejects the dialectic as a criterion of knowledge for “lack of qualification”, he accepts the general procedure as a logical tool, and acknowledges its applications in both technical rhetoric and practical oratory. In this way, “the rhetor is like the dialectician” (Ibid., II, 42, col. 30, I. 12.). The varieties of discourse are defined further at the end of this essay.

THE MIRAGE OF SUCCESS

False illusions of success encircle us. Salary is not a reflection of skill. Popularity is not a mirror of value. Wealth cannot enrich friendship. Power cannot procure safety. Usually, these things produce antithetical effects: success incentivizes corruption, popularity rewards dishonesty, wealth challenges friendship, and power instigates insecurity. In his Key Doctrines, Epíkouros warns, “If for every occurrence you do not constantly reference the goal of natural pleasure, but if you suppress both banishment of pain and pursuit of pleasure to operate for another purpose, your reasonings and practices will not be in accordance” (25).

Wishing to be worshipped and well-liked, people procured security from people so long as they can be pronounced popular. And if so then indeed they were safe since such a lifestyle inherits the natural benefit of the good. If, however, they procured no safety, then they did not receive that for which they initially strove. (Key Doctrine 7)

Philódēmos provides us with a further warning in On Rhetoric as well as an example of when politicians, wishing to be popular, failed to procure safety:

“[M]any statesmen have been rejected by their fellow citizens, and slaughtered like cattle. Nay they are worse off than cattle, for the butcher does not hate the cattle, but the tortures of the dying statesmen are made more poignant by hatred” (Ibid., I, 234, col. V).

Based on these factors, Hermarkhos calls those who willfully pursue a career in rhetoric “insane”. They rarely achieve the goal of nature that such wealth and popularity is meant to secure. He affirms that “’It is better to lose one’s property than to keep it by lawsuits which disturb the calm of the soul‘” (Ibid., I, 81, 3ff.=Suppl. 40, 23 ff). For “it is much better to lose one’s wealth if one can not keep it otherwise, than to spend one’s life in rhetoric” (Ibid., I, 235, col. VI). Epíkouros summarizes, “Better for you to have courage lying upon a bed of straw than to agonize with a gold bed and a costly table” (Usener, Epicurea 207).

LIVE UNKNOWN

“[L]et us be content”, writes Philódēmos, “to live the quiet life of a philosopher without claiming a share in the ability to manage a city by persuasion” (On Rhetoric, I, 234, col. IV). Nothing secures a pleasant life so much as friendship, and nothing guarantees a life of pain so much as politics. Philosophy is more valuable that rhetoric because the “philosophy that teaches us how to limit our desires is better than rhetoric which helps us to satisfy them.” (Ibid., II, 150, fr. VII)

Philosophy is more profitable than epideictic rhetoric, especially if one practices rhetoric in the fashion of the sophists […]. The philosopher has many τόποι [“topics” or “positions”] concerning practical justice and other virtues about which he is confident; the busybody (i. e. the rhetorician) is quite the opposite. Nor is one who does not appear before kings and popular assemblies forced to play second part to the rich, as do rhetors who are compelled to employ flattery all their lives. (Ibid., I, 225, fr. I).

Escape notice and live! So writes Philódēmos, every “good and honest [person] who confines [their] interest to philosophy alone, and disregards the nonsense of lawyers, can face boldly all such troubles, yea all powers and the whole world.” (Ibid., II, 140, fr. XII). He observes:

“inspired before the same loud clamor, some will strive with the effort of Apollophanes [the Stoic] to advance wonderfully to the podium, but others, having landed in [philosophy’s] harbor and with hopes offered them that ‘not even the venerable flame of Zeus would be able to prevent them taking from the highest point of the citadel’ a life that is happy, afterwards, in spite of opposing winds….” (P.Herc 463)

A GALAXY CLOSE TO HOME

If you will humor me, and entertain the possibility that I might attempt to “rightly hold dialogue about both music and poetry” (Laertios 10.120), consider that many of these points have been artfully orchestrated by writer and director Tony Gilroy in the television series Star Wars: Andor. One character in the fiction, the galactic senator, Mon Mothma, highlights the perils of propaganda (and political office) by exposing a dangerous, manufactured narrative: her dissent in politics has made her a target, and her agency as an orator is being suppressed. She redresses the Senate one, final time before withdrawing to a base, hidden deep in a distant forest:

The distance between what is said and what is known to be true has become an abyss. Of all the things at risk, the loss of an objective reality is perhaps the most dangerous. The death of truth is the ultimate victory of evil. When truth leaves us, when we let it slip away, when it is ripped from our hands we become vulnerable to the appetite of whatever monster screams the loudest. (Season 2, Episode 9)

In this fiction, diplomatic puppets defend and regurgitate loaded propaganda, having been convinced that a small, non-violent protest was actually an uprising. Only the survivors of the massacre, who heard the screams and saw the bodies for themselves know the truth. Similarly, Epíkouros advises that there “is a need to take into account […] all of the self-evident facts, according to which we refer our opinions”. Otherwise, “if not everything will be full of foolishness and of confusion” (Key Doctrine 22). Otherwise, one might be mislead to excuse genocide in the name of “security”. Otherwise, one might be mislead by political pundits and influential personalities to defend an armed mob of triggered, masked agents, deputized by a corrupt system to act with impunity. In the drama, one stormtrooper even shoots a woman in the face.

Trust your physical feelings and the force of nature. Lies are impractical. Propaganda is self-destructive. Oratory can be sinister. Principally, they target those who dismiss evidence and embrace superstition. It is dangerously easy to compel gullible minds to commit acts of violence through persuasive speech. Indeed, the modern-French philosopher Voltaire (heavily influenced by the propositions of the Epicurean school) observed that “Certainement qui est en droit de vous rendre absurde est en droit de vous rendre injuste” (Questions sur la Miracles 412). “Those who can make you believe absurdities can make you commit atrocities.” Persuasion is dangerous, and we rightly treat the instruments by which it spreads with scorn.

No deceptive speeches, manipulative oratory, lofty dialectic, nor rhetorical bullshit will convince a wise person to doubt their own eyes, discard their own feelings, and abandon their own study of nature. I invite you to see with your own eyes. Your life likely depends on it.

INDEX

-

- Technical rhetoric includes epideictic, encomiastic, and panegyric or sophistic types. Philódēmos teaches that these methods of rhetoric are true arts.

- Practical oratory includes ambassadorial, deliberative (or symbouleutic), and forensic types. Statesmen employ these methods for practical functions.

- Political discourse “in this respect […] may fittingly be compared to the art of prophecy” (Ibid., I, 31, 3 ff.=Suppl. 17, 20 ff.). It is sometimes practical.

- The Dialectic is a systemic, but deeply flawed method of reasoning privileged by

- Socratics, Megarians, Academics, Peripatetics, and Stoics.

- The Method by Analogy refers to the empirical reasoning of the Epicureans, which draws inferences from observations that can then be tested.

- Philódēmos mentions several other rhetoric types, including the entuectic and eristic types that are not explicitly categorized, and may be synonyms or subsets.

- AMBASSADORIAL ORATORY – πρεσβευτικός (presbeytikós). This practical form of oratory is employed by dignitaries and diplomats. Ambassadorial oratory is the ability “to be able to persuade in diplomatic negotiations by speech, not by power or bribes or dignities or anything else an ambassador might possess” (Philódēmos, On Rhetoric, II, 217, col. XIII).

- DELIBERATIVE ORATORY – συμβουλευτικά (symbouleutiká) is also known as “symbouleutic” oratory. This practical form of oratory is used by legislators. It “gives advice only on matters affecting the common welfare, and that this advice is not the product of the sophistic art, but of [something] quite a different…” (Ibid., I, 211. Col. XXX.19).

- EPIDEICTIC RHETORIC – ἐπιδεικτικός (epideiktikós, “demonstrative”, “performative”). This is an art of study regarding “charming speeches” (Ibid., II, 244, col. XLII). It is also called “encomiastic” by Stoics (Laértios 7.142). It is far less profitable than philosophy “especially if one practices rhetoric in the fashion of the sophists” (Ibid., I, 225, fr. I.).

- ENCOMIASTIC RHETORIC – ἐγκωμιαστικός (enkōmiastikós, “eulogistic” or “laudatory”) is rhetoric ἐπαίνους καὶ ψόγους (epaínous kai psógous) “of praise and blame”. “Furthermore, no one can believe encomiasts, because they praise bad men” (Ibid., 220, col. XXXIXa). Stoics called epideictic oratory “encomiastic” (Laértios 7.142)

- ENTEUCTIC SPEECH – ἐντευκτικόν ἅπασιν (enteuktikón ápasin, “obtaining favor with the multitude”). The Peripatetic Dēmḗtrios of Phalēreús adds the enteuctic type of rhetoric to Aristotélēs‘ group of three (On Rhetoric, I, 222, 6). This deals with presentation.

- ERISTIC SPEECH – ἐριστικός (eristikós, “eager for strife”). “Dialectic and eristic may be arts…” , however, the Epicurean school evaluates them as forms of persuasion, unconcerned with the validity of their statements as they correspond to reality (Ibid., I, 57, 23 ff=Suppl. 29, 15 ff.). Eristic speech is provocative and controversial.

- FORENSIC ORATORY – δίκανικα (díkanika, “judicial”). Philódēmos compares the practicality of forensic oratory with “deliberative” and “ambassadorial” oratory (Ibid., I, 134, col. XXXI). Practically, forensic oratory is employed in courts of law in the form of criminal defense.

- PANEGYRIC RHETORIC – πανηγυρικός (panēgyrikós, “assembly” speech). This form of rhetoric is synonymous with sophistic rhetoric. “Now we have already treated in a previous section the idea that sophistic or panegyric or whatever it may be called […] may be easily called rhetoric.” (Ibid., II, 234. col. XXXV.). Epíkouros writes that the wise “will not πανηγυριεῖν (panēgyrieîn)” or “make public speeches” (Laértios 10.120).

- POLITICAL DISCOURSE – πολιτικός (politikós, “of the city”). Politics, by itself, is not an art. By itself, the “political faculty” is empty. It is not a technique, nor a method, but more like “prophecy”. “No man was able […] to impart to his contemporaries or to posterity [the principles of politics]” without the rhetorical arts of the philosophers (Ibid., I, 139, col. XXXIV). “[T]echnical treatises of rhetoricians […] are useless for producing the political faculty”, which does not require training (On Rhetoric, I, 64, II frr.=Supple. 32, 19 ff.).

- PRACTICAL ORATORY – Practical forms of oratory (for example, speeches employed by dignitaries, deliberations employed by legislators, and defenses employed by lawyers) are distinguished from technical rhetoric (epideictic or enconmiatic, and panegyric or sophistic). Practical oratory is not considered an art that can be learned, only a practice that can be repeated, like civic speech, legislative debate, judicial defense, and diplomatic counsel. “Epicurean authorities hold that sophistic rhetoric does not perform the task of practical and political rhetoric” (Ibid., I, 119, 28 = Suppl. 59., 1e4. I, 120, 10= Suppl, 60, 6).

- SOPHISTIC RHETORIC – σοφιστική (sophistikḗ). Sophistic is an art of epideixis, and of the arrangement of speeches, written and extemporaneous.” (Ibid., II-c). “Sophistic style is suited to epideictic oratory and written works, but not to actual practice in forum and ecclesia” (Ibid., III, 134. fr. V). Indeed, “the training given by the sophists does not prepare for forensic or deliberative oratory” (Ibid., II, 131, fr. I). “Sophistic can “persuade men to become villains. And when they do praise a good man they praise him for qualities considered good by the crowd, and not truly good qualities” (Ibid., I, 216 col. XXXVa, 14).

- TECHNICAL RHETORIC – τεχνικός (tekhnikós, “technical”) refers to methods of oratory that properly fit the Epicurean definition of an “art” (or “technique”), including epideictic and sophistic methods. Technical rhetoric offers methods (as is the case with any true art) that can be taught, and reproduced to achieve the same result. “Two sciences produce the same result.” (Ibid., I, 4, co. I=Suppl. 4, 17.). However, compared against the study of nature, “technical rhetoric has never advanced anyone” (Ibid., I.192, col. XI).

- THE DIALECTIC – διαλεκτική (dialektikḗ). Before the idealistic Hegelians and materialistic Marxists, the “dialectic” was privileged by Socratics, Megarians, Academics, Peripatetics, and Stoics, who defined it as “the science of conversing correctly where the speeches involve question and answer — and hence they also define it as the science of what it true and false and neither” (Laértios 7.42). The Epicureans reject the dialect as being incapable of verifying “truth” because it assumes that “truth” is capable of being reasoned without reliance upon physical evidence. Most of the dialecticians encouraged political participation as a necessity to existential satisfaction; Epicureans outright reject political office.

- THE METHOD BY ANALOGY – ὁ καθ᾽ ὁμοιότητα τρόποϛ (ho kath’ homoiotēta tropos, “method according to similarity”) anticipated the modern, scientific method by several millennia. Epíkouros accepted that inferences must comport with observation and abide by nature. We must “create an analogy that corresponds with what we see“ (On Nature, Book 11, III, b5-12).” [W]e shall not be prevented from making inferences, provided that we use the method of analogy properly” (On Signs). And “we say that the method of analogy is a sound method of inference, with this condition, that no other appearance or previously demonstrated fact conflicts with the inference” (Ibid.).

For additional commentary, please see “Reasonings About Philodemus’ Rhetoric”

For more on deliberate misrepresentation, please see “On Bullshit” by Dr. Harry Frankfurt

Be well and live earnestly!

Your Friend,

EIKADISTES

Keeper of Twentiers.com

Editor of the Hedonicon