Disclaimer: the ideas and opinions presented below are reflective of the author and may or may not be shared by other members of the Society of Friends of Epicurus.

PART I: THE ATOM PROPHET

Prior to ingesting psilocybin mushrooms at the age of 20, my theological positions were categorically Kyrēnaíc — as with “Theódōros, known as the atheist”, I “utterly rejected the current belief in the gods” whether they be Olympians, the Stars, or the Trinity (Laértios, Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers 2.86, 2.97). Like The Atheist, I, too “denied the very essence of a Deity” (Cicero, On the Nature of Gods 23). I was equally “great at cunning up anything with a jest”, happily reducing holy stories to hoary myths, lampooning the paradoxically pregnant virgin, teasing the tyranny of a childish creator, and “using vulgar names” for embarrassing social phenomena that appeared (to me) to be plagues upon the rational world, like hordes of superstitious rats, marching to the tune of their petty pipers (Laértios 4.52). I viewed the faithful as flocks of lost sheep following false shepherds. I rejected the religious experience as, at best, a benign delusion, and, at worse, untreated psychosis.

Then the blue meanies hit.

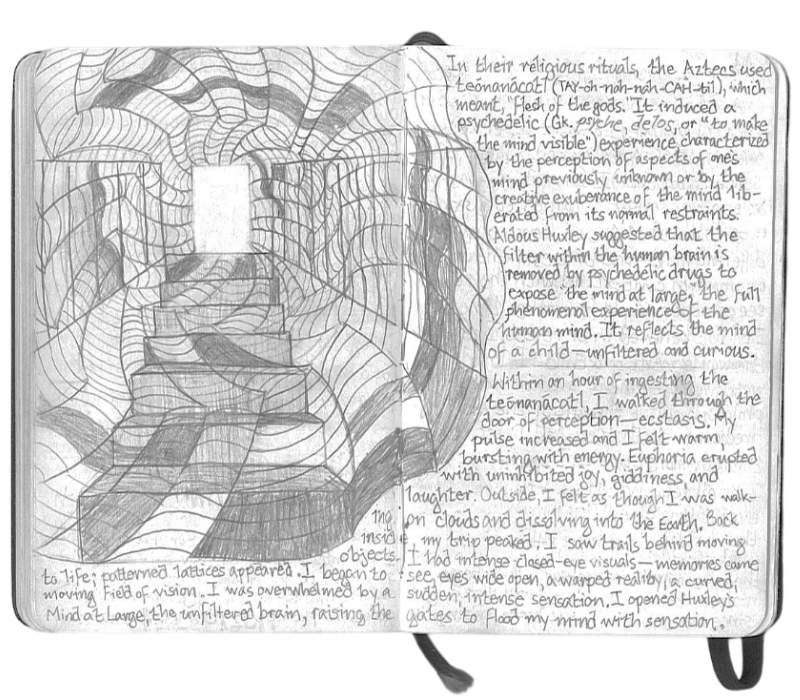

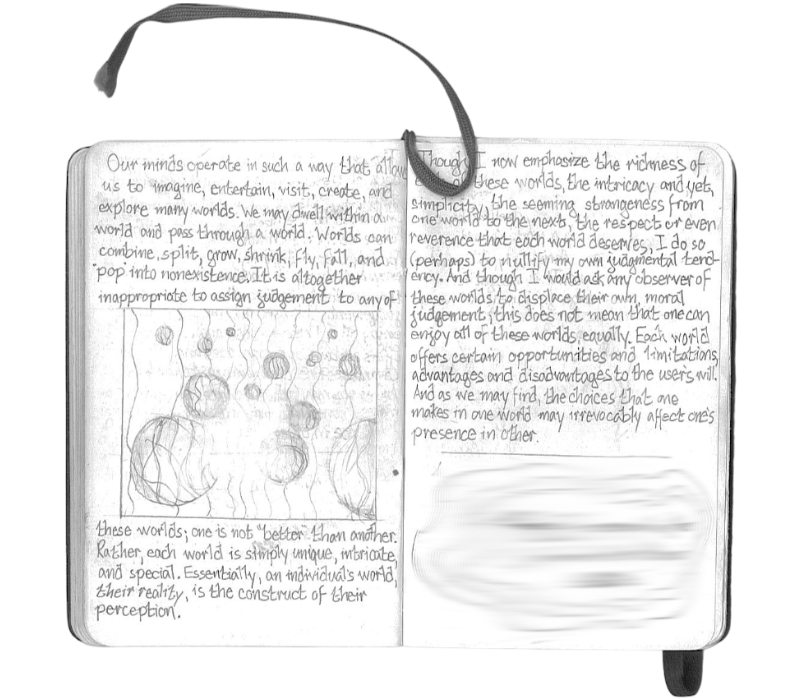

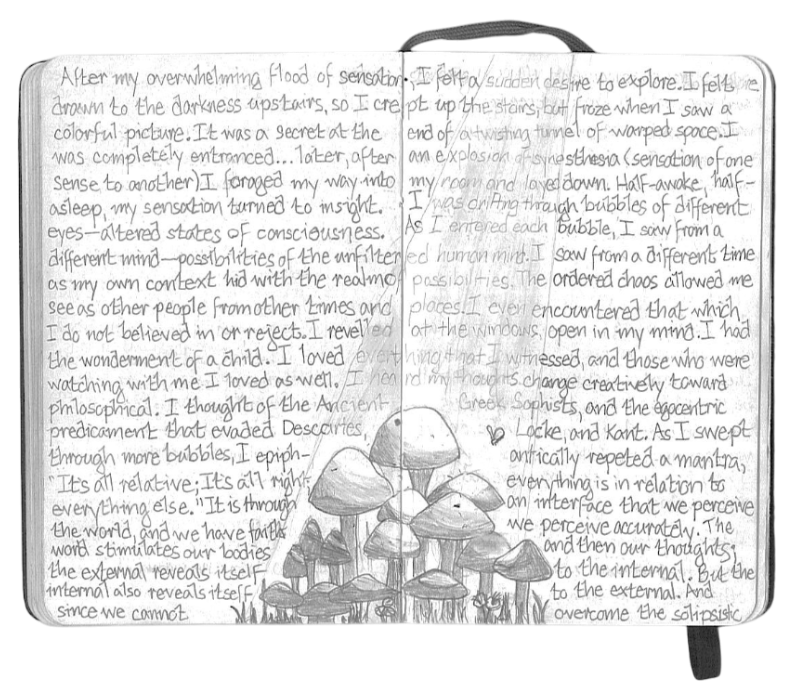

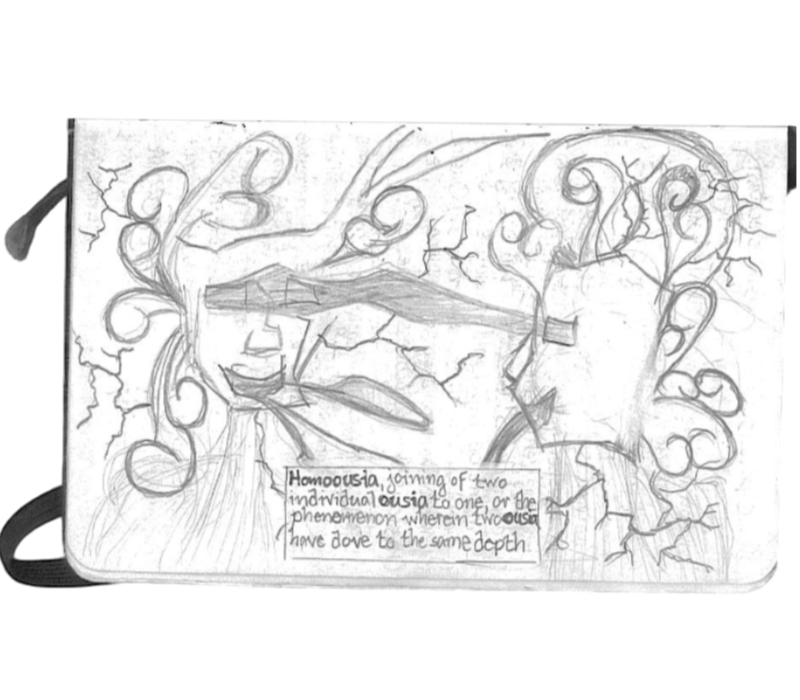

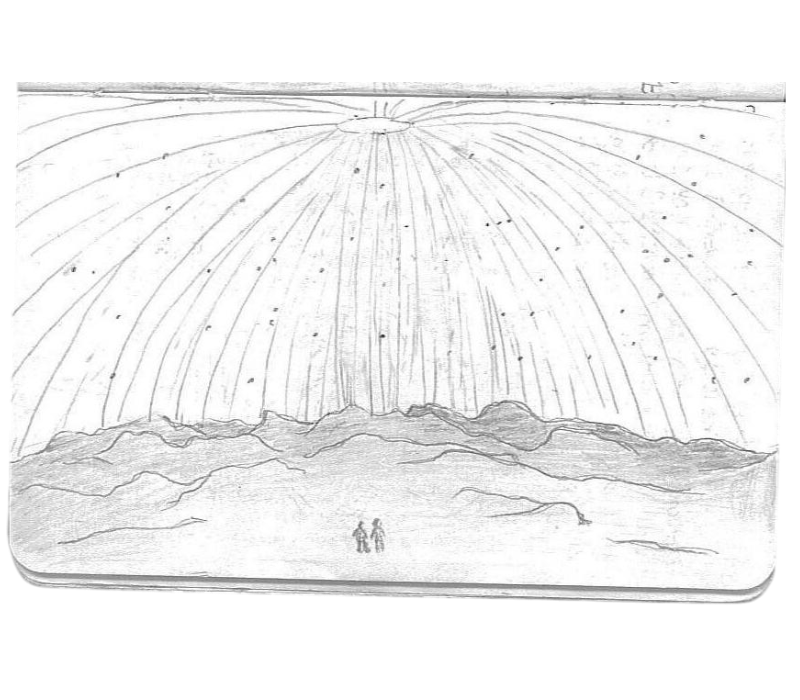

“Door of Perception” from an unpublished diary (June 2009).

I walked through the doors of perception ― ecstasis. My pulse increased and I felt warm, bursting with energy. Euphoria erupted with uninhibited joy, giddiness, and laughter. Outside, I felt as though I was walking on clouds and dissolving into the Earth. Back inside, my trip peaked. I saw trails behind moving objects. I had intense closed-eye visuals ― memories came to life; patterned lattices appeared. I began to see, eyes wide open, a warped reality, a curved, moving field of vision. I was overwhelmed by a sudden, intense sensation. I opened […] the unfiltered brain, raising the gates to flood my mind with sensation. (Unpublished Diary, June 2009)

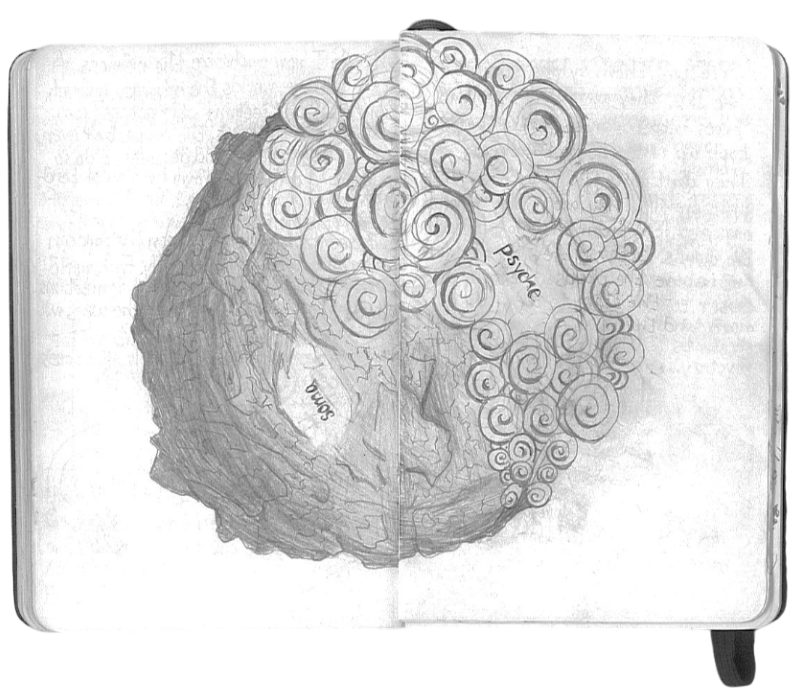

The symptoms of the psychedelic experience, from the ancient Greek ψυχή (psykhḗ or “soul”) and δῆλος (dḗlos or “visible”), are exquisitely unique and reliably illuminating, if such insights can be apprehended — the flood of perceptual fluctuations that engulfs the ego often inundates the analytical faculties. Consequently, should one hope to return from the abyss triumphant, with the gift of bliss and the reward of wisdom, the intellect must stretch its reach, wielding an extended net of metaphor to capture the juicy insights swimming around it.

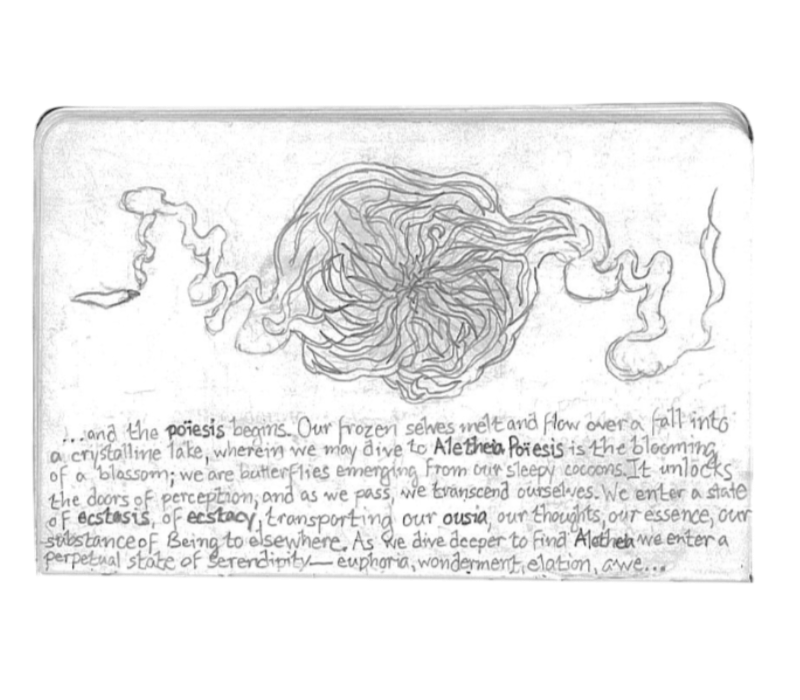

Half-aware, half-asleep, my sensation turned to insight. I was drifting through bubbles of different eyes ― altered states of consciousness. As I entered each bubble, I saw from a different mind ― possibilities of the unfiltered human mind. I saw from a different time as my own context hid with the realm of possibilities. The ordered chaos allowed me see as other people from other times and places. I even encountered that which I do not believe in or reject. I reveled at the windows open in my mind. I had the wonderment of a child. I loved everything that I witnessed, and those who were watching with me I loved as well. I heard my thoughts change, creatively toward the philosophical …

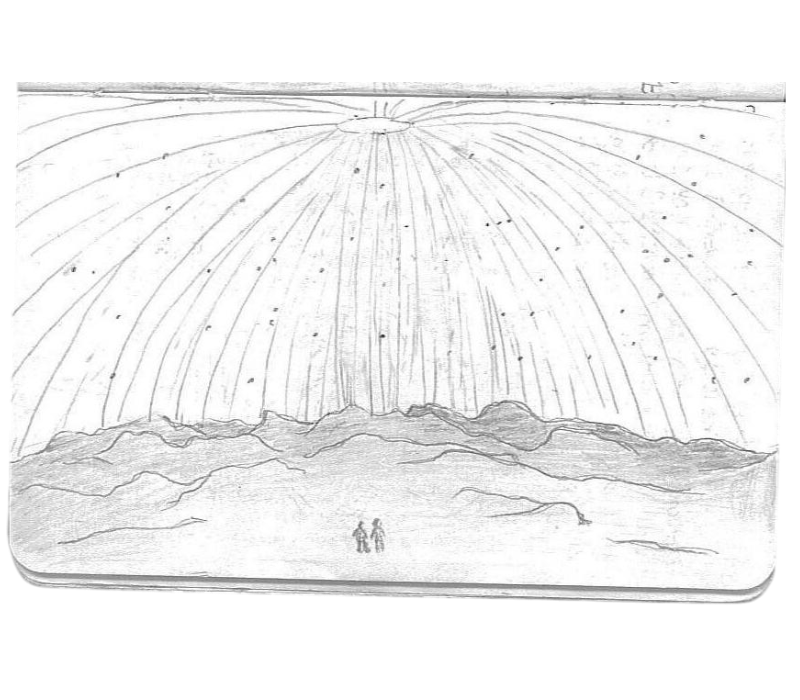

“The Realm of Psyches” from an unpublished diary (June 2009)

As sometimes happens, four grams of fungus triggered an existential deconstruction that challenged a host of perceptual certainties and inspired a journey to the edge of the soul.

I thought of the ancient Greek Sophists, and the egocentric predicament that evaded Descartes, Locke, and Kant. As I swept through more bubbles, I repeated a mantra, “It’s all relative; it’s all right; everything is in relation to everything else.” It is through an interface that we perceive the world, and we have faith that we perceive accurately. The world stimulates our bodies and then our thoughts; the external reveals itself to the internal. […] We cannot afford to limit ourselves to our own interface. We must transcend our own limitations. Falling asleep, I repeated the mantra, “All right, it is all right…”

The next morning, the tone of my theology transformed from the dismissive scorn of a faithless Kyrēnaíc to the confident assurance of a pious Epicurean, an “Atom-Prophet” observant of the material divinity within. While I was still unconvinced by popular expressions of faith, still suspicious of religious institutions, still scornful of magical thinking, dismissive of superstitious beliefs, and derisive of supernatural myths, I became convinced of a universal spirituality, a primal faith that conforms to physics, driven by chemical ecstasy, ritualized across innumerable cultures, each featuring the same symptoms of the psychedelic experience.

The impression of that event shines in my mind like a holy relic, a splinter from the true cross of ecstasy. I returned from the psychedelic realm with a gift of bliss and sacred testimony, having communed with the kaleidoscopic source of experience, liberated from vain, intellectual inflexibilities. Before that event, I reduced the religious experience to a mere neurological disturbance; but as an Epicurean, I elevate that experience to a neurological blessing. Far from being an empty construct the requires dismissal, the “divine nature” is palpable. The meanings of mythic metaphors become evident as the conditioned realm of assumptions and prejudices dissolves into void. The psychedelic sacrament cleansed my mind of toxic opinions and purged me of rage. I was kissed by blessed psilocybin, who left me with a lasting euphoria.

The founder of the Epicurean tradition defends this material form of ὁσιότητος (hosiótētos) “piety” while criticizing the misunderstandings of the masses and their misleading myths. He maintains that the “true” gods are “not the same sort the masses consider” who “continuously pray for cruel” punishments “against one another” (Epíkouros, Epicurea 388). It is not the godless Kyrēnaíc, “but the one who adheres to the masses’ doctrines about the deities” who is truly “impious” (Epistle to Menoikeus 123). “For pious is the person who preserves the […] consummate blessedness of God” versus those who ask “in prayer” for “things unworthy of the supposed indestructibility and complete blessedness” of the divine (Philódēmos, On Piety, Col. 40.9-13 and Col. 10.2-5). “Such a person we honour for his piety, whereas the other we despise as manifestly depraved” (Ibid., Col 41.1-5). Any other, incoherent “definition of piety […] gives a strange impression, partly of jealousy, and partly of hostility” (Ibid., Col. 65.7-11).

In essence, Epicurean theology affirms that “God” is neither employed as an administrator in cosmic government, nor appointed as a magistrate to establish metaphysical jurisprudence. “The gods” neither probe the universe for life like interstellar anthropologists, nor prey upon shapely bachelorettes, nor worry themselves with weather forecasts. True piety observes the divinity found in nature, in forming bonds, cultivating friendship, and securing tranquility through peaceful relations. “Piety appears to include not harming” (Ibid., Col 47.5-8). Indeed, “piety and justice appear to be almost the same thing” (Ibid., Col. 78.10-12). In the Epicurean tradition, piety is an acknowledgement that god does not direct the human drama. A true deity neither fulfills vain wishes like a genie, nor practices divination like a sorcerer, neither seeking power from a fear of death, nor seeking fickle approval to gain favor. They are neither omnipotent nor omniscient, neither causative nor administrative, but only exhilarative, inter-generational sources of inspiration from which the rituals of religion have been formed.

PART II: PARTY ANIMALS

And with regard to festivals and sacrifices and all such things generally, it must entirely be acknowledged that he acted in accordance with what he believed and taught and that he faithfully employed oaths and tokens of good faith and he kept them. (Philódēmos, On Piety, Col. 51.3-11)

While the Sage of the Garden is distinguished for his critical commentary against hypocritical beliefs and mythic deceit, he nevertheless contributes volumes of reflections on spiritual wisdom and religious practice, faithfully exhorting a friend to “consider the deity an incorruptible and blessed figure” (Laértios 10.123). Philódēmos records Epíkouros as having “loyally observed all forms of worship” since he “enjoined upon his friends to observe them, not only on account of the laws, but for physical reasons as well. For in On Lifecourses he says that to pray is natural…” (On Piety, Col. 26.5-14). Philódēmos later affirms:

He shared in all the festivals […] joining in celebrating the festival of the Choes and the […] Mysteries and the other festivals at a meagre dinner, and that it was necessary for him to celebrate this feast of the twentieth for distinguished revelers, while those in the house decorated it most piously, and after making invitations to host a feast for all of them. (Col. 28.18–Col. 29.10)

The public festivals that Philódēmos names include both “the festival of the Choes” or “the Pouring”, the second day of the three-day-long, flower-and-wine holiday of Anthestḗria, celebrated on the twelfth day of the eponymously-named month of Anthestēriōn (from ἄνθος or ánthos meaning “flower”), as well as τά Μυστήρια (tá Mystḗria) or “the Mysteries” — it is unclear whether Philódēmos means μυστήρια τ’άττικα (mystḗria t’áttika Col. 28.27-28) “the Attic” (perhaps Eleusían) Mysteries versus μυστήρια τ’άστικα (mystḗria t’astiká “the Urban Mysteries” or “City Dionýsia” held during the month of Elaphēboliōn (mid-March-to-April), known for its theatrical competitions, reminiscent of contemporary fringe festivals. By extension, Epíkouros may also have observed the adjacent Dionysian festival of Λήναια (Lḗnaia) from ληνός (lēnós meaning “wine-press”) in honor of Dionýsios Lēnaíos (“of the wine-press”), celebrated in Epíkouros’ birth-month of Gamēliṓn, from γαμηλίᾰ (gamēlía) meaning “marriage” (mid-January-to-February). The Lesser Mysteries may also have been patronized by Epíkouros and his friends, which also transpire during the month of Anthestēriōn. These holidays share many of the same wedding, drinking, parading, and feasting features as Anthestḗria.

A number of contemporary scholars have attempted to reconstruct a portrait of the central rituals that defined these holidays including a wedding procession, a symbolic pageant, a symbolic marriage, performances, drinking games, dancing, an animal sacrifice, and the filling feast that followed. Among them, Henri Jeanmarie orchestrates the following scene:

[T]he procession was led by a flute player, followed by basket bearers in white dresses, with flowers in the baskets. Others carried the perfumed altar, then there followed the maritime cart containing the God. Next there came a flute player and participants carrying flower wreaths raised high, so that they formed a kind of arc or superstructure. Under this walked the sacrificial bull, decorated with white ribbons. The procession also included masked men dressed up as women, fertility demons and satyrs. […] Upon arrival at the sanctuary the procession met with the Basilinna or queen, and her fourteen priestesses who received Dionysos in the wagon. | Those participants who performed the secret rituals in the sanctuary dedicated to Dionysos in the Marshes, comprised a group of fourteen priestesses called gerarai (“the Venerable Ones”), the holy herald, and the Basilinna, who was the wife of the Archōn Basileus, the priest of Dionysos, who during his year of service was responsible for many of the older religious ceremonies […] during the ritual […] the animal sacrifice was also performed […] When the women’s rituals in the Marshes were finished, Dionysos then married the Basilinna, who, as already stated, was the wife of the Archōn Basileus. He presided over the festival, and played the role of the God in the hieros gamos […] After having fetched the bride, the colorful procession walked through the city […] Meanwhile women and men stood outside the doors and on the terraces of their houses, carrying lighted torches in their hands and watching the procession as it passed by. (Håland 406-409)

In a letter to his friend and co-founder Polýainos, Epíkouros insists that “Anthestḗria too must be celebrated”, beginning with [DAY 1] Πιθοίγια (Pithoígia) the “Casket-Opening” during which “libations were offered from the newly-opened jars to the god of wine” and “all the household, including servants or slaves [joined] in the festivity of the occasion” — so long as that person was “over three years of age…” (Encyclopædia Britannica 103). Pithoígia resembles in many ways the Celtic tradition of Samhain, as well as its Christian analogue, All Hallow’s Eve save that Pithoígia is set amidst the floral scenery of Anthestēriṓn (mid-February-to-March), just in time for the wine to have reached its intended perfection as the flowers of next year’s harvest begin to bloom. Participants, within fragrant “rooms […] adorned with spring flowers” would, expectantly, open their tall πίθοι (píthoi, “jars of wine”) anticipating the prize within — symbolically, the jars represent the “grave-jars” of the deceased: fumes from the the previous season’s vintage escape like the vapors of the departed, liberated from their dark tombs. The souls of the dead are mythologized to have escaped the underworld to torment the living. “To protect themselves from the spirits of the dead,” as was the Attic tradition, Athenians were seen “chewing ‘ramnon’, leaves of Hawthorn, or white thorn, and were anointing themselves and their doors with tar” (Psilopoulos, Goddess Mystery Cults and the Miracle… 268).

As noted by Philódēmos (On Piety), the following day of Anthestḗria was designated [DAY 2] Χοαί (Khoaí) or Choës meaning “The Pouring” — naturally, the “pouring of the cups” would follow the “opening of the jars”. Fortunately, for our survey, “literary testimony [of] the second day, the Choes” “is explicit” (Prolegomena to the Study of Greek Religion 39). The day is “dedicated to a hieros gamos, a wedding of the Gods”. It famously featured a “drinking contest, to celebrate the arrival of the God” (Greek Festivals, Modern and Ancient 406). Despite “the drinking contest, the flower-wreathed cups”, the family feasts, “and the wedding of Dionysos, all joyful elements of the service of the wine-god, the Choes was a dies nefastus, an unlucky day” that demanded pious observance (Prolegomena 39). “On the part of the state this day was the occasion of a peculiarly solemn and secret ceremony in one of the temples of Bacchus, which for the rest of the year was closed.” (“Anthesteria”, Encyclopedia Brittanica). It is within this context that the Hegemon affirms “it is necessary to make mention of the gods” (Philódēmos, On Piety, Col. 30.28-29). Epíkouros provides us with the following appeal:

Let us sacrifice to the gods […] devoutly and fittingly on the proper days, and let us fittingly perform all the acts of worship in accordance with the laws, in no way disturbing ourselves with opinions in matter concerning the most excellent and august of beings. Moreover, | let us sacrifice justly, on the view that I was giving. For in this way it is possible for mortal nature, by Zeús, to live like Zeús, as it seems. (Epistle to Polýainos)

One example of a “sacrifice” to which he alludes might be found in the libations offered during the final day of Anthestḗria [DAY 3] Χύτροι (Khýtroi), an ancient predecessor of Día de los Muertos, the Day of the Dead. “The third day was explicitly dedicated to the spirits of the dead” (Greek Festivals, Modern and Ancient 413). Practitioners would offer the contents of their χύτραι (khýtrai) or “[cooking] pots” to Hermes Chthónios, a deity of the ancient underworld — here, Hermes fulfills the role of a classical psychopomp whose function it is to guide departed souls through the unfamiliar terrain of the afterlife. The pots of pious devotees would contain a porridge called πανσπερμία (panspermía or “all-seeds”), a warm “meal of mixed grains” (A Companion to Greek Religion 336). Such a sacrifice, characterized by personal abstinence and modest renunciation, would have exemplified Epikouros’ conception of αὐταρκείας (autarkeías) or autarky, meaning “self-sufficiency”, “self-reliance”, or “independence” (a notable ἀρετή or aretḗ, meaning “virtue” or instrumental good). Epicurean autarky is further characterized as a freedom from vain desires. The Master writes that “we praise the [virtue of] self-sufficiency not so that one might be in want of things that are cheap and plain, but so we can have confidence with them” knowing that the best things in life, like friendship, are free (Epicurea U135b).

Beyond his participation in the traditional civic festivals and cults of the Athenian polis, Epíkouros established a number of sect-specific holidays for friends and future students. As recorded in his Last Will, the observances he recommends include:

…an offering to the dead thereupon for both my father and my mother and my brothers, and for us the practice having been accustomed to celebrate our [Epíkouros and Metródōros’] birthday of each year on the Twentieth of Gamēliṓn, and so long as an assembly comes into being each of the month celebrate on the Twentieth to philosophize for us in order to respect both our memory and Metródōros’. And then celebrate the day of my brothers for Poseideṓn, and then celebrate that of Polyainos for Metageitniṓn exactly as we have been doing. (Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers 10.18)

The Epicurean practice of ritualizing the anniversary of one’s birthday will strike us as a familiar celebration, yet in ancient Greece, “birthdays” were unrecognized outside of Persia. The historian Hēródotos records that “of all the days in the year, the one which they” the Persians “celebrate most is their birthday. It is customary to have the board furnished on that day with an ampler supply than common” (Customs of the Persians 1.133). It was even traditional to prepare pastries or cakes, for they ate “little solid food but abundance of dessert, which is set on table, a few dishes at a time” (Ibid.). Birthdays for Epicureans signify “the blessedness of having come into existence, for having become part of Nature’s vast and awesome realities” (A Companion to Horace 329). Epíkouros writes that “the wise will have gratitude for friends both present and absent alike through both word and through deed” (Laértios 10.118). In treating our friends’ birthdays as holidays (“holy days”), we observe a classical expression of piety.

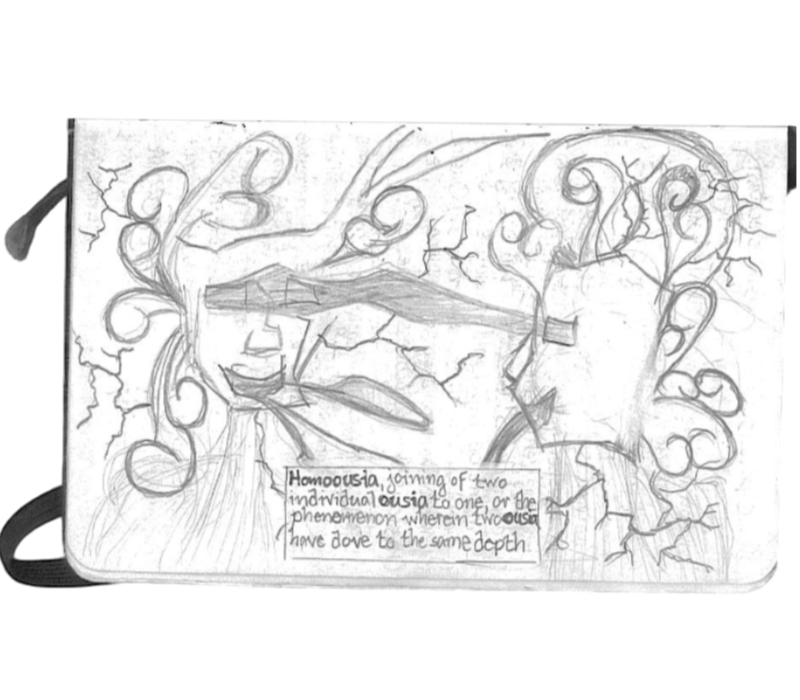

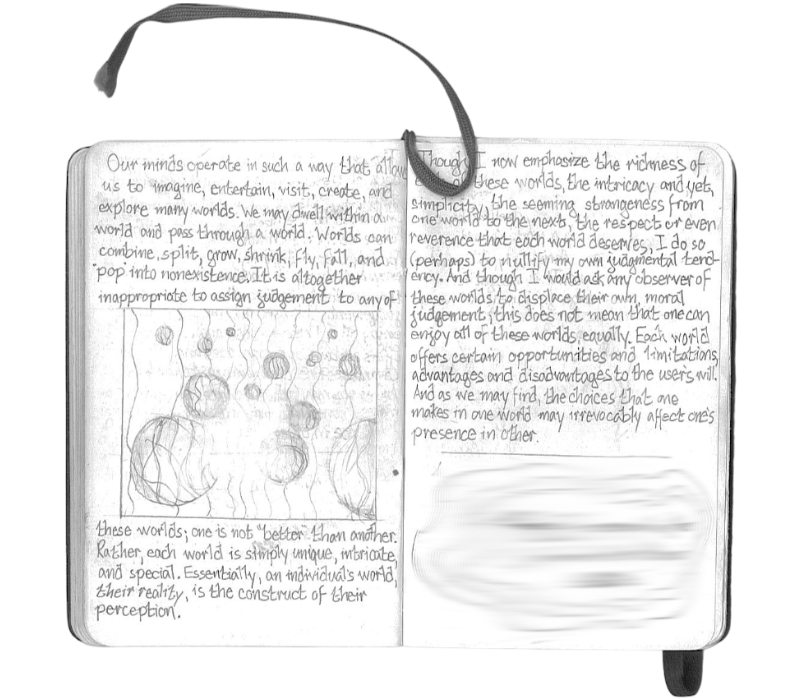

“Homoousian” from an unpublished diary entry (June 2009).

While birthdays provided celebrants with an opportunity to toast the living, days of remembrance provided celebrants with an opportunity to venerate the dead. Epíkouros reserves a number of days in memoriam — he sets aside funds to provide resources for memorials for his father, his mother, and commemorations for his brothers on a day in Poseideṓn (mid-December-to-January), as well as his two, deceased best-friends, Polýainos on the 6th of Metageitniṓn (mid-August-to-September) and Metródōros on his own birthday of Gamēliōn 20th (mid-January-to-February). Polýainos’ day likely overlapped the festival of Metageítnia (for which the month was named), a a feast commemorating the legendary migration of Apollo Metageitniṓn, holy patron of migrants (an analogue for the modern personification of Lady Liberty). Apollo Metageitniṓn may have been a sympathetic icon for members of the Athenian Garden, many of whom were migrants from Lámpsakos or refugees to Athens.

Memorial cults in the ancient world were usually observed on the death-days of the deceased (not the days of their birth), so it is possible that Polýainos died on the 6th of Metageitniṓn (P.Herc. 176). At the same time, hero cults celebrate the birthdays of the figures of their veneration annually, and the Hegemon presents his school as such. Epíkouros neither establishes a funerary cult to support the ghosts (in which he did not believe) of his fallen friends, nor a mortuary cult to ritualize their internment. Instead, he prescribes a hero cult for himself and his friends in the hope that future students might learn from their lives and benefit by emulating their examples. In addition to the obligatory feast that crowns each festival, days of remembrance provide devotees with opportunities to clean gravesites and decorate votives.

In addition to participating in civic festivals and private rites, Epíkouros formally establishes the celebration of Eikas (or “The Twentieth”) the so-called “Philosopher’s Sabbath”, the unifying Epicurean holiday, a symposium, open to friends, associates, and acquaintances, set on the 20th day of each month. Several ancient inscriptions, carved in stone preserve the name of an older cult known as οἱ Εἰκαδεῖς (oì Eìkadeîs), those bound by the mythic hero Εἰκαδεύς (Eìkadeús), worshipped as a manifestation of Apollo Parnessiós (a form of Apollo who resides on Mt. Parnassós, surrounded by muses and strumming a lyre). The Eìkadeîs, too, worshipped their patron on the 20th day of each month; indeed, a deity cult would observe its patron god monthly, whereas a hero cult would celebrate their heroes annually: a “monthly cult was reserved for divinities” (The Cambridge Encyclopedia to Epicureanism 24). Thus, in establishing a monthly practice for his tradition, Epíkouros was “moving as close to the gods as was humanly possible” (Diskin Clay, Paradosis and Survival: Three Chapters in the History of Epicurean Philosophy 97). Indeed, “the festival for which the Epicureans were best known [was] established on the Apollonian day”. “The date, the twentieth of the month, was an interesting choice by Epicurus. For that was a sacred day to the celebrants of Apollo at Delphi and it was also the day on which initiation rites were held at the Temple of Demeter in Eleusis” (Hibler, Happiness Through Tranquility: The School of Epicurus 18). In organizing monthly gatherings, Epíkouros was explicitly providing initiates with a non-supernatural alternative to the predominant cults that ritualized transcendence and resurrection. “In derision, the enemies of the Master named his cult Eikadistai which is from the Greek word for the twentieth” (Ibid. 18).

Epíkouros and his καθηγεμώνες (kathēgemṓnes) “co-guides” or “co-founders” established a school that moonlit as a naturalistic hero cult with religious undertones. They provided an alternative to the dominant superstitions that circulated among the masses and founded a tradition that welcomed the unwelcome. Ancient Epicureans expressed their piety by hosting feasts, participating in festivals, attending pageants, patronizing theatrical sanctuaries, venerating the living (i.e. anthropolatry), memorializing the dead, committing to a study of nature, exercising peaceful relations, honoring friendships, and meditating upon the visualizations of divinities, divinities like Ζεύς (Zeús), whose name is derived from a prehistoric word for the archetypal god of the day sky, Dyēus. (As an interesting historical sidenote, Zeus was frequently epitomized by the epithet Ζεύς Πατήρ or Zeús Patér, from which we inherit “Jupiter”, a continuation of the proto-Indo-European phrase “Dyēus Ph₂tḗr” meaning “Sky Father”.)

PART III: BY ZEUS!

Epíkouros published a number of treatises on theology, including Περὶ Ὁσιότητος (Perì Hosiótētos or “On Piety”) and Περὶ Θεῶν (Perí Theôn or “On Gods”). In his texts, the Gargettian encourages worship of the gods while maintaining the validity of atomic physics and highlighting the emptiness of the supernatural. Elsewhere in his texts, the Sage of the Garden conducts a survey of religious history, provides an evaluation of the efficacy of rites and rituals, and he reflects upon the nature of the profound mental impressions that have inspired thousands of years of pious devotion. While these masterpieces have been lost, his ideas have been preserved by Philódēmos’ similarly-named works “On Piety” and “On Gods”, in addition to Metródōros’ Περὶ Μεταβολής (Perì Metabolês or “On Change”), and a work by Demḗtrios of Lakōnía entitled Περὶ τοῦ Θεοῦ Μορφῆς (Perì toû Theoû Morphēs or “On the Form of a God”), within which the form and physics of the divine depictions are further deconstructed.

These texts preserve a variety of theological attitudes, characterized by flexibility and fluidity, compatibility and coherence. Casually, the authors shift between polytheism, henotheism, kathenotheism, qualified monotheism, monolatry, and thealogy. They observe infinite deities, patronizing some, revering others, preferring these, ignoring those, favoring the feminine, venerating the masculine, and honoring the conceptual unity that the multiplicity of gods compliment. Each of these theological positions exhibit coherence between the variations in our internal understandings of blessedness as they have been “manifest” (as Demḗtrios of Lakoniá suggests) to the mind’s eye. The deities are expressions for the divine nature, paragons of the divine nature, and participants in the divine nature. At times, their names are invoked reverently, as when Philódēmos offers a “drink in honor of Zeus the Savior” (On Death 3.32) while at other times, their literary forms are employed as purely poetic devices, as when Philódēmos summons “Aphrodite” and “Andromeda”, or when Diogénēs of Oìnóanda patronizes “father Zeus” (153) and swears “in the name of the twelve” (128). Hermarkhos records the Hegemon as having exercised this same practice: “Concerning metaphor, he made use in human fashion of the connection with the (divine) entity” (Against Empedoklḗs). The Epicurean sages demonstrate themselves to be skillful rhetoricians who shift their tone appropriately, casually, creatively, technically, and frankly. As Epíkouros writes, “Only the wise will rightly hold dialogue about […] poetry” (Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers 10.120).

When he isn’t dropping the names of gods as idioms (e.g. NH ΔIA, Nḗ Dία or “By Zeus!”) and expletives (e.g. ΠΑΙΑΝ ΑΝΑΞ, Paián Ánax meaning “Lord Paian!” compared with our swear “Jesus Christ!”), Epíkouros is describing a collective group of θεῶν (theṓn) “of [the] deities” in the genitive plural (Epistle to Menoikeus 124, 133, 134; Vatican Saying 65). Elsewhere we find the word “deities” as θεοὺς (theoùs) in the accusative plural (Ep. Men. 123, 139), θεοῖς (theoîs) in the dative plural (Ep. Men. 123), and θεοὶ (theoì) in the vocative plural (Ep. Men. 123). Epíkouros employs the singular word “deity” as θεὸς (theòs) in the nominative (135, U338), θεόν (theón 121, 123, 134) in the accusative, and θεῷ (theôi 134) in the dative, both with and without a definitive article (“the” deity versus simply “deity”). Three times in the Epistle to Menoikeus, Epíkouros employs the masculine pronoun “him” when referring to “the deity” in the accusative (αὐτὸν or aútòn), dative (αὐτῷ or autōî), and genitive declensions (αὐτοῦ or autoú 123). Concurrently, throughout his abridgment on meteoric phenomena, Epíkouros employs feminine expressions for “the divine nature”, found in the nominative (θεία φύσις or ḗ theía phýsis, Ep. Pyth. 97, 117) and accusative forms (τὴν θείαν φύσιν or tḗn theían phýsin 113).

Jesus Christ! I find myself refreshed by the flexible means with which Epíkouros expresses divinity. I am equally encouraged by the possibility of an inclusive, intelligible approach to spirituality, independent of incoherent myths and tyrannical clerics. Such a congenital expression of piety compliments my continued observation that religious establishments and mythic narratives have been artificially fabricated. The larger story of human history reflects a tale of animals who developed histories, cultivated civilizations, and generated religious icons over vast periods of time, all due to the simple swerve of tiny, cosmic threads.

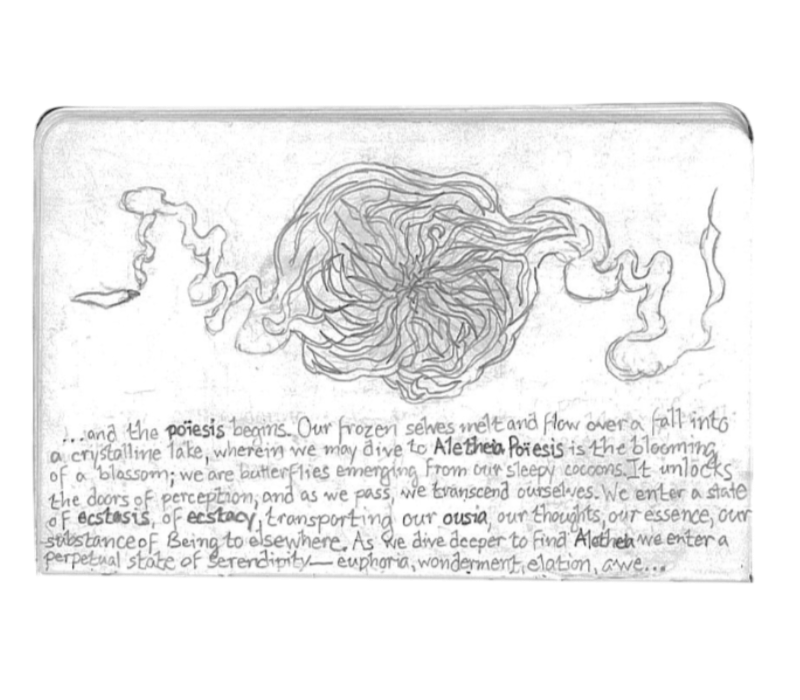

“Poesis” from an unpublished diary (June 2009)

According to Cicero, Epíkouros “alone first founded the idea of the existence of the Gods on the impression which nature herself hath made on the minds of all men” (On the Nature of Gods 26). “For what nation, what people are there, who have not, without any learning, a natural idea, or prenotion, of a Deity?” According to the Gargettian, pre-historic humans first conceived of divinities as sublime psychological icons encountered during dreams and meditations (On Nature 12). The Pyrrhonian skeptic Sextus Empiricus preserves Epíkouros’ historical thesis: “The origin of the thought that god exists came from appearances in dreams” as well as godlike examples manifest among “the phenomena of the world” (Adversus Mathematicos 9.45-46). Far from being prophetic symbols θεόπεμπτος (theópemptos) “sent by the gods” (Diogénēs of Oìnóanda, fr. 9, col. 6), the delightful visions are, most immediately, mental representations apprehended from a “constant stream of” materially-bondable “images” (Laértios 10.139). Ancient humans’ internal encounters with these untroubled forms created deep impressions in their minds. The devotees developed conventions to celebrate the symbols of their insights. Traditions were cultivated and pious practice flourished, as did dramatic myths and misunderstandings. Eventually, “self-important theologians” and deluded priests diluted beliefs about the divine and perverted piety with a fog of fear (Philódēmos, On Piety, Col. 86A 1-2). God, himself, was assigned disturbing duties and became enlisted in the service of religious autocrats.

Contrary to the chilling myths championed by “self-important theologians”, the true nature of the divine knows no need to direct the production of the human drama. Epíkouros recognizes that “it is foolish to ask of the gods that which we can supply for ourselves” (Vatican Saying 65). The true benefits of worship are enjoyed by worshippers, not by the fantastic objects of our obeisance. Humans conceive of gods and goddesses as being kind, confident, and self-reliant; in practicing these virtues, we cultivate our own happiness: “Anyone who has these things […] can rival the gods for happiness” (Vatican Saying 33). Philódēmos exhorts us to “imitate their blessedness insofar as mortals can” and “endeavor most of all to make themselves harmless to everyone as far as is within their power; and second to make themselves so noble” (On Piety Col. 71.16-19, 23-29). Therefore, a correct understanding of theology and religious practice is integral to cleansing oneself of the turmoil that is symptomatic of magical thinking. Millennia later, the American diplomat Benjamin Franklin recycles this ancient aphorism in his publication Poor Richard’s Almanack, suggesting that “God helps them that helps themselves.”

PART IV: ALL PARTICLES GO TO HEAVEN

To rationally explore concepts like divinity and prayer, Epíkouros defines a standard of knowledge that is grounded in atomic interactions — “the criterion of truth [includes] the sensations and preconceptions and that of feeling” (Laértios 10.31). The Gargettian defines the divine nature (“the gods” or “God”) as being presented by the mental προλήψις (prolēpsis) “impression” of μακαριότητα (makariótēta) “blessedness”, also described as τελείαν εὐδαιμονίαν (teleían eùdaimonían) “perfect happiness”. The gods of Epíkouros are primarily θεωρητούς (theōrētoús 10.62, 135) “observed” or “contemplated” as φαντασίαν τῇ διανοίᾳ (phantasían tḗi dianoíai) “visualizations” or “appearances [in] the mind” (10.50). Epíkouros affirms that the gods μὲν εἰσιν (mèn eísin 123) “truly exist” yet are only “seen” or “reached” through an act of λόγῳ (lógoi 10.62, 135) “contemplation”, “consideration”, “reasoning”, “reckoning”, or “logical accounting” (10.62, 135). He observes that the mental φαντάσματα (phantásmata) or “appearances” of the gods arise ἐκ τῆς συνεχοῦς ἐπιρρύσεως τῶν ὁμοίων εἰδώλων (èk tḗs synekhoús èpirrū́seōs tṓn homoíōn eidṓlōn) “from a continuous stream of similar images” that leave impressions upon the mind. The divine impressions are generated from the coalescence of “similar images” through a process of ὑπέρβασις (hypérbasis) “sublimation”. The images the intellect apprehends have been ἀποτετελεσμένωι (ápotetelesménōi) “rendered” to human souls in human forms, inspiring, perpetually-healthy, perfectly-happy people.

Having reviewed the psychiatric evidence of memory against the criteria of knowledge (exemplified by the Epicurean canon), Epíkouros explains that the functional “coherence” or “resemblance” between internal φαντάσματα (phantásmata) “appearances” and external τοῖς οὖσί (toís ousí) “reality” (or literally, “the beings”) requires an initial impulse to complete a sequence of successive impacts, ultimately yielding a perception in the mind, “since we could not have sought the investigation if we had not first perceived it” (Laértios 10.33). A sensible τύπος (týpos) “impression” initiates a perceptual relay through various pathways in the soul — the sense organs are stimulated by acoustic ῥεύμᾰτᾰ (rheúmata) or “currents”, olfactory ὄγκοι (ónkoi) or “hooklets”, and visual είδωλα (eídōla) or “images” “impinging [upon] us [as] a result of both the colorful realities and concerning a harmonious magnitude of like morphologies”. The μαχυμερέστερον (makhymerésteron) “marching army of particles” (Dēmḗtrios of Lakonía, On the Form of a God 21) enter “the face or the mind” […] yielding an appearance and an [affective] sympathy as a result of the observing” (10.49-50). The earliest people who experienced these visions assumed “the object of thought as a thing perceived in relation to a solid body […] understanding perception that can be grasped by corporeal sensation, which they also knew to be derived from a physical entity [i.e. nature].” (Philódēmos, On Piety, Col. 15.8-18). Thus, “the gods” were born, and forms of worship developed to venerate their appearance.

Mental phantasms can be instigated passively through the indiscriminate mechanism of sensation, either externally, through the trigger of touch, or internally, “in respect of slumbers” when the mind is least encumbered by daily disturbances. They can also be summoned intentionally, through a directed act of contemplation, involving τινὰς ἐπιβολὰς τῆς διανοίας (tinàs épibolàs tḗs dianoías) “some applications of the intellect” like μνήμην (mnḗmēn) “memory”. Dēmḗtrios of Lakōnía elaborates that the representations in the mind are caused “both as those memories manifest” through focus, “and also” by the physical impulse of “pre-existing [bodies] that, upon [striking] the mind produce constructive cognition” (On the Form of a God 12). Because of this, mental representations of religious figures can be summoned through meditation as readily as when gazing upon a the body of a physical icon. In prayer, the supplicant manually retrieves the mental impressions of blessed impulses from memory. Depictions of divinity have been “apparent” (and readily-available) to most people for millennia — the fields of the Earth are filled with statues, votives, frescoes, mosaics, murals, metalwork, jewelry, pottery, and architecture that glorify the divine. Each civilization peppers its conception of divinity with fresh colors, shapes, and stories just as each culture ritualizes a contemplative path to care for the health of the soul. In doing so, each group creates a cultural matrix into which subsequent generations are enmeshed. Concurrently, each tradition preserves its own, procedural means by which to make the contents of their psykhḗ become dḗlos.

When a supplicant prays, meditates, concentrates, reflects, or generally applies directed focus toward the memory of the “form” of “blessedness”, they generate a mental image “as if” practitioners were literally ἐν εἰκόνι (én eìkóni) “in the presence” of a physical “representation”, “portrait”, or “icon”. As with the memory of “brightness”, “loudness”, “softness”, and “sweetness”, the mental “appearance” of a divine form arises ἐκ τῆς συνεχοῦς ἐπιρρύσεως τῶν ὁμοίων εἰδώλων (èk tḗs synekhoús èpirrū́seōs tṓn homoíōn eidṓlōn) “from a continuous stream of similar impulses” received from abroad. To further isolate the genesis of our conceptions, we can trace the atomic crumbs of cognition to their energetic source. In the case of divine entities, we discover that our representations have been conditioned through our experiences with human nature combined with the congenital preconception of blessedness. As with the preconception of δίκαιος (díkaios) “justice”, the mental prototype of a “god” functions as an organizing principle and can act as a standard against which real-world examples can be evaluated — an alleged divinity who punishes and terrorizes neither meets the definition of “blessed” nor of “just”, and cannot, by definition, be “a god”. So long as a personal conception of divinity coheres with the definition of “blessedness”, it can be considered to be a god. Thus, an endless collection of divinities can be perceived, in a variety of forms, supported by the infinity of particles.

The intelligible form of a god appears to us, as does each, conceptual formation in the mind, as τὸ ὄν (tò ón) “a being” or “an entity” (Philódēmos, On Piety 1892, 66a 11). According to Epíkouros, each “entity” can be conceived of as an individual ἑνότης (henótēs) “unity” or “union” composed of many other particles that coalesce together to form representational σύγκρισεις (sýnkriseis) “compounds” in the mind. As Metródōros writes, each ἑνότητα ἰδιότροπον (henótēta idiótropon) “distinctive unity” also exists as a “compound made up of things that do not exist as numerically distinct” (On Change; in Philódēmos, On Piety, Col. 4.13-15). Epíkouros clarifies, “unified entities” in the mind exhibit one of two constitutions — some “are perfected out of the same elements and others from similar elements” (On God; in Philódēmos, On Piety Col. 8.14-17) The φύσεις (phýseis) “natures” or “constitutions” of all of these “unified entities” are therein grouped according to the origin of their birth, either from a single source, or having coalesced from multiple sources ἐξ ὑπερβάσεως τῶν μεταξύ (èx hyperbáseōs tôn metazù Col.12.8-9) “as a result of transposition” during traversal “between” the source and its representative conception in the mind. If the mental form of an entity is composed of particles that only originate from a single source, Epíkouros says that they are all αὐτή (autḗ) “the same” in constitution — “the same” form is one that reflects a numerically-singular entity in one’s environment. By contrast, Epíkouros says that the appearances composed of particles coming from multiple sources are only superficially ὁμοία (homoía) “similar” because they are only related insofar as their composition as an array of εἴδωλα (eídola). Besides their shared form as bundles of images, they have different origins that combined during conception.

To demonstrate this constitution, visualize a dog. The appearance of this dog is a mental representation. It was previously impressed upon your mind when dog-particles travelled from a dog through spacetime and impacted your eyes. The resulting dog-form is a bundle of distinct particles that correspond κατ’ ἀριθμόν (kat’ arithmón) “in number” to the measurable proportions of “that same”, furry creature in reality. Your representation is composed of particles whose φύσεις (phýseis) “origins” are all αὐτή (autḗ) “the same” — your internal perception of a “dog” is uncontaminated from the particles of other, distinct objects. The generative flow of images reflects the activity of the original body, and a dog is not confused for another form (e.g. when dog-forms coalesce with human-forms in our imagination, we picture werewolves).

Next, visualize a god (any god. Take your pick. Any such forms will do.) Like the dog-form, your god-form is a mental image. Like the dog-form, the god-form is also apprehended by the intellect. Like the dog-form, the god-form too was initially triggered by impulses “received from abroad”. However, unlike the mental aggregate that constitutes your impression of a “dog”, your impression of a “god” is a ὑπέρβασις (hypérbasis), a “superimposition” of at least two different bodies of εἴδωλα (eídola) that are only superficially ὁμοία (homoía) “similar” insofar as their material composition as a picture in the mind. The compound nature of these images enables their being ἄφθαρτον “indestructible”. By comparison, after the death of a dog (and the end of that dog’s eídola), that dog’s form can only be retrieved from memory — we are left with the impressions that a mortal creature gave us of itself during its limited lifespan. The forms of the gods, however, are not at risk of dissolution because they do not have a single source that is subject to death — the sources of the god-forms are unending, undying, and limitless, the infinite soup of particles that is constantly interlacing before our very souls. In this regard, “the form of god” is neither a simple body (like a particle), nor a regular compound (like a dog), but is a sort of irregular compound. Neither compound is a simple body (i.e. a particle), and both are combinations of simple bodies, but unlike the mental form of “a dog”, the mental form of “a god” is not composed of particles that are κατ᾽ ἀριθμὸν (kat’ árithmòn) “numerically-identical” to their source, but rather, the form of “a god” is composed of particles that are καθ᾽ ὁμοείδειαν [kath’ hòmoeídeian] “similar in consistency” such that they can become enlaced to imagine new forms — the image of a human mixes in the mind with the concept of perfect happiness, as well as other notions, like agelessness to form the idea of “God”. Epíkouros explains οὓς μὲν κατ᾽ ἀριθμὸν ὑφεστῶτας (oús mèn kat’ árithmòn hyphestṓtas) “on one hand” the forms of the gods appear to be “subsisting by number”, as though each on is a “unified entity”; “but on the other hand” οὓς δὲ καθ᾽ὁμοείδειαν (oús mèn kath’ hòmoeídeian) it is also the case that the gods are formed from multiple sources due to their substantial existence “as a consistency” or “similarity” of images that produce “a common appearance”, or “likeness” (Laértios 10.139).

In the case of the specific characteristics of the form of a god, our mind seems to universally apprehend any given representation of the divine nature ἀνθρωποειδῶς (anthrōpoeidṓs) “as-a-human-idol” or “anthropomorphically” (Ibid. 139). Granted, they are not “to be considered as bodies of any solidity […] but as images, perceived by similitude and transition” (Cicero, On the Nature of the Gods 28). “We do not find the calculation” so writes Demḗtrios, “that any other shape” besides that “of the human” could qualify as a blessed and incorruptible being.” Indeed, the gods “are granted to be perfectly happy; and nobody can be happy without virtue, nor can virtue exist where reason is not; and reason can reside in none but the human form” (Ibid.). Philódēmos writes that “we have to infer from the appearances” of their characteristics. Indeed, the form of a god is “conceived as a living being” (On Gods III, Col. 10):

One must believe with Hermarchus that the gods draw in breath and exhale it, for without this, again, we cannot conceive them as such living beings as we have already called them, as neither can one conceive of fish without need in addition of water, nor birds [without additional need] of wings for their flight through the air; for such [living beings] are not better conceived [without their environment] .

Philódēmos further reflects on the dwelling-place of the gods:

[E]very nature has a different location suitable to it. To some it is water, to others air and earth. In one case for animals in another for plants and the like. But especially for the gods there has to (be a suitable location), due to the fact that, while all the others have their permanence for a certain time only, the gods have it for eternity. During this time they must not encounter even the slightest cause of nuisance… (On Gods III, Col. 8).

The Epicurean scholarch Apollódōros, the “Tyrant of the Garden” infers that that “the dwellings” of the infinite gods “have to be far away from the forces in our world”, not necessarily by distance, but impalpability (On Gods III, Col. 9). The ghostly forms of the gods transcend the perils of our perishable plasma through a perpetual replenishment of spectral particles, motes, most minor and minute, as the most minuscule molecules of the human mind.

Philódēmos acknowledges that the deities possess perception and pleasure. Their behavior is recognizably human-like, finding delight in thought and conversation:

…we must claim that the gods use both voice and conversation to one another; for we will not conceive them as the more happy or the more indissoluble, [Hermarchus] says, by their neither speaking, nor conversing with each other, but resembling human beings that cannot speak; for since we really do employ voice, all of us who are not disabled persons, it is even the height of foolishness that the gods should either be disabled, or not resemble us in this point, since neither men nor gods can create utterances in any other way. And particularly since for good men, the sharing of discourse with men like them showers down on them indescribably pleasure. And by Zeus one must suppose the gods possess the Hellenic language or one not far from it, and that their voices in expressing rationalist are clearest… (Philódēmos, On Gods III, Col. 13)

The innumerable forms of the deities seem to be enjoying the greatest-possible happiness, a perfect happiness, that which cannot be heightened by excess. They seem ceaselessly-satisfied, savoring friendship and pleasure, “for it is not possible for them to maintain their community as a species without any social intercourse” (Philódēmos, On Gods, fr. 87). Unburdened by the undue responsibilities of celestial governance, astral adjudication, and cosmic corrections, the holy inhabitants of the mind are wholly self-reliant. Perfectly prudent, they privilege the preservation of their own peace above other obligations. As living figures, they seemingly breathe; as social figures, they seemingly converse; as intelligent figures, they seemingly reflect; as blessed figures, they live without fear, paragons of imperishability and models of ethical excellence.

Demḗtrios notes that, “when we say in fact the God is human-shaped” we should remember that God is not actually human (On the Form of a God 15). Velleius explains in On the Nature of the Gods that god “is not body, but something like body; nor does it contain any blood, but something like blood” (28). Though, he adds,“these distinctions were more acutely devised and more artfully expressed by Epicurus than any common capacity can comprehend”. They are, nonetheless, “real”, “unified entities”, even as appearances in the mind.

In order that he might “realize” his own “fulfillment”, scrutinizing the forms of these “beings surpassing [ὑπερβαλλουσῶν or hyperballousōn] in power [δυνἀμει or dynámei] and excellence [σπουδαιότητι or spoudaiótēti]”, who equally “excel [ὑπερέχον or hyperékhon] in sovereignty [ἡγεμονίαν or hegemonían]”, Philódēmos infers that:

… that of all existing things, [the divine nature] is the best [ἄριστον or áriston] and most holy [σεμνότατον or semnótaton, “dignified” or “revered”], most worthy of emulation [ἄξιοζηλωτότατον or áxiozēlōtótaton, “enviable”], having dominion over all good things [πάντων τῶν ἀγαθῶν κυριευόντα or pántōn tōn agathṓn kurieúonta], unburdened by affairs [πραγμάτευτον or pragmáteuton], and exalted [ὑψηλόν or hypsēlon, “sublime” or “proud”] and great-minded [μεγαλόφρονα or megalóphrona, “noble” or “generous”] and great-spirited μεγαλόψυχον or megalópsykhon, “magnanimous”] and ritually pure [ἅγιον or hágion, “sacred”] and purest [ἅγιοτατον or àgiōtaton, “holiest”] and propitious [ῑ̔́λεων or hī́leōn, “blameless”]. Therefore they say that they alone strive after the greatest form of piety and that they hold […] the purest views as regards the ineffable [ἄφραστον or áphraston, “inexpressible” or “marvelous”] pre-eminence [ὑπεροχήν or hyperokhēn, “superiority”] of the strength [ἰσχύος or ìskhúos, “power”] and perfection [τελειότητος or teleiótētos, “completeness”] of the divine [toû theíou] […] [Epíkouros] advises not to think [God] bad-tempered (as he is thought), for example, by the poets. (On Piety, Col 45.2-30).

PART V: THE MYSTERIES

It might seem counter-intuitive for an atomist to have embraced categorical mysticism, but history is unequivocal, “in Epíkouros’ case” his capacity to entertain mystical practices “is shown by his eagerness for sharing in των Ἀθήνησιν μυστηρίων (tōn Athḗnēsin mystḗríōn) the mysteries at Athens” (Philódēmos, On Piety, Col. 20.6-11). Both friends and opponents attest to this point, including Timokrátēs, the former Epicurean and estranged brother of Mētródōros, who implicates the Hegemon of having engaged in μυστικὴν ἐκείνην (mystikēn hekeínēn) “mystical fraternizations” at night (Laértios 10.6). Epíkouros rejects any inerrant interpretations of the mythic fictions, but still, he committed to attendance. From the attestations provided by Philódēmos, Epíkouros recognized the practical psychological (or spiritual) benefits from the induction of a mystical experience. Indeed, the “mind-manifesting” features of psychedelia provide a bridge to support an image-based conception of “the deities” as described by the Gargettian, otherwise only privately manifest to the mind’s eye. Epíkouros establishes this coherence with his theory of knowledge. His observations laid a framework with which to explain the dynamics of religious ecstasy, divine madness, and psychedelic mysticism.

We inherit the word “mystery” (μυστήριον or mystḗrion) from the verb μύω (mýō) meaning “close” or “shut”, as in “shutting [one’s eyes]”. Therein, the μύστης (mýstēs) “initiate” or “mystic” is one who seeks to minimize external disruptions and maximize the conscious absorption of internal phenomena (parenthetically, we also inherit the words “myopia” and “myopic” from μύω or mýō). The rituals in which the mýstēs participates are called μυστήρια (mystḗria) the “Mysteries”, and the qualities of the private ceremonies and the ecstatic visions for which mystics anticipated are described as μυστικός (mystikós) “mystical”.

Though the language of mysticism is Greek, the family of practices and altered states to which it refers are universal. Ecstasy can be elicited via trance, auto-hypnosis, contemplation, prayer, meditation, sex, fasting, dancing, music, focused breathing, and through chemical induction by means of an entheogen (Pahnke 1962). The analytical contents of these exercises might be further illuminated by concepts like “the Perennial Philosophy” of Aldous Huxley, the “religious experience” of William James, the “collective unconscious” of Carl Jung, and the “universal myths” of Joseph Campbell — these seem to me, in particular, to be reasonable attempts by devoted thinkers to map the territory of the human mind.

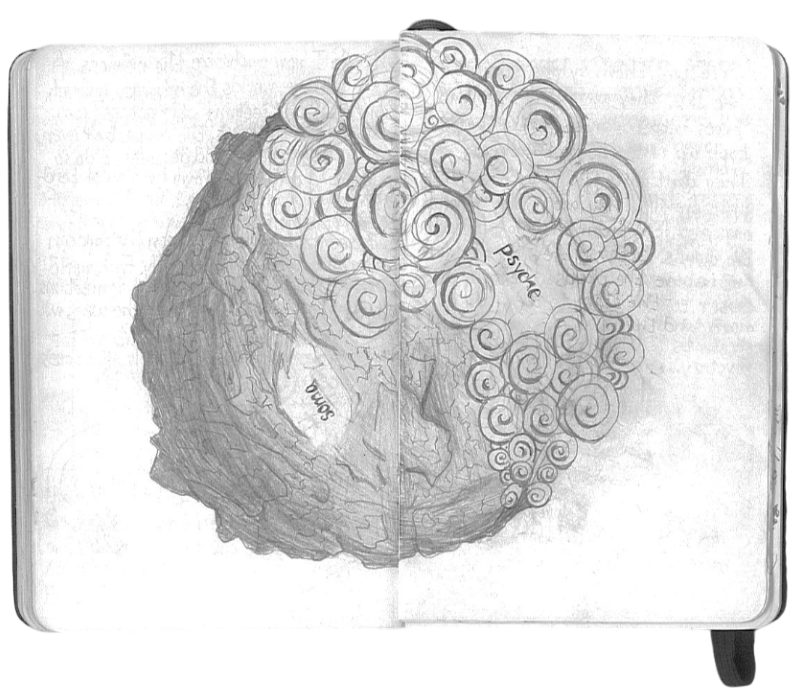

“Psyche-Soma” from an unpublished diary (June 2009).

Religious institutions also offer helpful analogues against which we can compare and contrast both ancient mystería as well as modern psychedelia. Consider the variety of rituals and beliefs that contribute to visionary experiences, such as the Orthodox practices of “théōsis” and “apothéōsis”, or the Roman Catholic process of “deification” or “divinization”, as well as the corresponding practice of ἡσυχασμός (hēsykhasmós) “inward stillness” established by the the Desert Monastics from which apothéōsis it received. Hesychasm corresponds with the contemplatio “contemplation” of the early Christian Fathers of the Church — incidentally, the word contemplatio is a translation of θεωρία or theōría, the same word that Epíkouros employs to refer to the traditional means by which the deities manifest — of those Church Fathers, several of them dually identified as Platonists or Neo-Platonists. Like the Christians whom they inspired, the Neo-Platonists developed the practice of Theoria as a means of engaging divinity. Whereas Christians sought “the presence of God”, so Neo-Platonists sought union through ἕνωσις (hénōsis) “two from one” with the “Monad”, “the One”, or “the Absolute”. Incidentally, Neo-Platonism, itself, is a partial, Academic re-branding of Hindu Vedanta by the founder of Neo-Platonism, Ammṓnios Sakkás, a possible, Indian mystic named from the ancient Śākya clan (from which the Brahmin family of Siddhartha Guatama hailed, eight centuries earlier).

The Neo-Platonic ἕνωσις (hénōsis) provides a direct conceptual link between visionary Greek and Indian wisdom traditions. A similar parallel exists between the Greek θεοφάνεια (theopháneia) “appearance of a deity” and the Dharmic दर्शन (darśana) “sight of a divinity”. Other constructs that presents similar (though not identical) examples, including the Hindu notions of प्रज्ञा (prajñā) “insight” and विद्या (vidya) “knowledge”, the Buddhist term बोधि (boddhi) “enlightenment”, which corresponds with the Chinese word 見性 (kenshō), and the Japanese word 悟り (satori). It may be further helpful to compare the “divine madness” of Plato (Phaedrus 244-245; 265a–b) with the “enlightenment” constructs of the Indian subcontinent, including समाधि (samādhi), मोक्ष (mokṣa), and निर्वाण (nirvana). We also find some correspondence with the Sufi practice of مراقبة (Murāqabah) “observance”, as well as the γνῶσις (gnōsis) from various Gnostic sects. Many of these traditions that achieved mystical states through psycho-physical exercises also incorporated entheogens (from ἔνθεος or éntheos, “possessed by a god”) that trigger chemognosis (from χυμεία or khymeía, “art of mixing alloys” or “alchemy” that leads to divine γνῶσις or gnôsis, “[secret] knowledge”).

While the aforementioned practices and states of consciousness are not at all identical, nor even completely translatable, they help exemplify some of the ways in which traditions have been shared and re-formulated since pre-history. In addition to the earlier-mentioned link between “Jupiter” and the proto-Indo-European god “Dyēus Ph₂tḗr” meaning “Sky Father”, we see ancient examples with the Pyrrhonists, who adopted the wisdom of the ancient Indian अज्ञान (Ajñana) mendicants and re-branded it to the ancient world as “Skepticism”. In return मध्यमक (Madhyamaka) Buddhists’ borrowed the epistemological methods of the Pyrrhonists. The late Academics’ synthesized the philosophy of Plátōn with Hindu Vedanta and sold the entire program as “Neo-Platonism”. Centuries earlier, it seems that Greek materialists borrowed atomism from their वैशेषिक (Vaiśeṣika) counterparts in India. (The dimensions of these historical traditions have been explored more thoroughly elsewhere, and readers are encouraged to expand on these ideas and properly delve into each tradition on its own accord.)

Each of these traditions shares levels of correspondence with τά Μυστήρια (tá Mystḗria) or “the Mysteries” that help reconstruct the particularities of those religious experiences that would been contemporaneous with Epíkouros (of which, there were many). The Eleusían mysteries were the most popular (of which Plátōn was fond), followed closely by the Dionysian mysteries (mentioned earlier) — and Orphic cults (of which Pythagóras was fond). The Orphic cult later inherited the Dionysian tradition, and heavily influence the context in which the Christian resurrection deity emerged. The Mysteries in which Epíkouros participated would have exposed him to psychedelic phenomena — even if, hypothetically, he never induced the mind-bending experience within himself, he would have heard the testimony of others, either from their own experiences, or popular lore. The visions that would have become activated under the influence of an entheogen would have corresponded with symbolic pageantry ritualizing the creation of life, the passage of the soul, the changing of seasons, the inevitability of death, the transition of the self, and the resurrection of the soul from the underworld through a mystery, shared only with the τελεστής (telestēs) meaning “initiator” or “priest” (Col. 32.11-12).

Anthestḗria and the Urban Mysteries are dedicated to Dionýsios (or Bákkhos, celebrated by the Romans during Bacchalania), so the Dionysian Mysteries may have been Epíkouros’ preferred mystery. As he relates to mysticism, Dionýsios is a transformational deity whose metamorphic powers ferment cheap grapes into rich wine and transmute simple produce into palliative potions — simultaneously, the soul of the initiate undergoes a procedural, psychiatric process of transformation that subjectively mirrors the seasonal procession of death and rebirth, animated through the subjective sense of having been psychologically reborn. The Mysteries celebrate this primordial nature that echos from the depths of the soul.

The Orphic tradition can be examined at length elsewhere, but in summary, the cult of Orphism ritualized the creation of humanity from the bodies of the recently-annihilated Titans and the soul of the recently-deceased Dionysos, son of Zeus. “In the later classical period, the Dionysus cult was adopted and adapted into the Orphic mysteries of death and rebirth, where Dionysus symbolized the immortal soul, transcending death” (Metzner). Later writers equated Orphism with the Pythagorean school. Both traditions influenced Plátōn, as they share the common belief in μετεμψύχωσις (metempsýkhōsis), “the-process-after-incarnation” or “reincarnation.” This theme of rebirth is central to the Mysteries. The Orphic cult also shares significant topical consistency with the resurrection deity of early Christianity — both deities are sons of a supreme God, both deities are killed by an ancient evil force, both deities are resurrected in spirit.

The Eleusían Mysteries were the most popular in ancient Athens, and may well have been the tradition in which Epíkouros may have ingested a holy sacrament. Like its counterparts, the Eleusían Mysteries developed from much earlier cults likely corresponding with Minoan and Mycenaean civilizations. The cult may originally have patronized Demeter, envisioned as a poppy goddess: “For the Greeks Demeter was still a poppy goddess, | Bearing sheaves and poppies in both hands”, thus, reinforcing a connection between psychoactive substances, ecstasy, and the formalization of religious rituals (Thekirtos VII 157). In Eleusis: Archetypal Image of Mother and Daughter, “Karl” Kerényi interprets the Eleusían Mysteries as having featured a sort of “epiphany”, “not as a vision for common eyes” but “visible only to the blind man in the hour of his death” (85). According to his personal translation of Plátō’s Phaídros, “the beatific vision” of “a goddess” transports an initiate “into a state of eternal beatitude” (95). As he writes, “divine apparitions” could “be induced by magical ceremonies” (114). According to Karl, a sacramental “pharmaceutical” was ingested to trigger “a real seeing, not as a subjective illusion”. He further speculates that this “pharmaceutical” involved an initiate needing to “drink the kykeon” to “attain a state of epopteia, of ‘having seen,’ by his own inner resources” (113).

The Elysian Mysteries were of two — the Lesser Mysteries took place during Anthestēriōn under the direction of the ἄρχων βασιλεύς (árchōn basileús) “lord sovereign” who would initiate “mystics” into the cult. The Greater Mysteries took place in Boedromiṓn (mid-September-to-October). Michael Cosmopoulos orchestrates the following scene:

On the first day [agrymós], the fifteenth of Boedromion, the Archon Basileus summoned the people in the Poikile Stoa. […] On the second day [élasis], the sixteenth […] the mystai proceed to either Piraeus or Phaleron, where they purified themselves by washing a piglet in the water of the sea […] On the third day, the seventeenth of Boedromion, there may have been sacrifices int eh Eleusionion under the supervision of the Archon-Basileus […] The fourth day and last day of [public] festivities in Athens was called Epidauria or Asklepieia […] it may have celebrated the introduction of the cult of Asklepios in Athens. […] On the fifth day, the nineteenth of Boedromion, a grandiose procession (pompe] took the hiera from Athens back to Eleusis. The procession started from the Eleusinion and proceeded through the Panathenaic Way and the Agora to the Dipylon Gates and from there followed the Sacred Way back to Eleusis. The mystai and their sponsors were dressed in festive clothes, crowned with myrtle wreaths, and held branches of myrtle tied with strands of wool (the “bacchos”). […] at the head of the procession were the priests and the Priestesses Panageis carrying the Hiera is the kistai […]Next in turn were the mystai and their sponsors. At the end of the procession were placed the pack animals with the supplies needed fo rhte long trip. The procession followed the modern highway from Kerameikos to the Sacred Way, up to the sanctuary of Aphrodite, where it turned toward the hill and the lakes of the Rheitoi before reaching the sea by the bridge. From that point the Sacred Way followed the modern highway once more. | During the procession two events took place: the krokosis would occur after the mystai crossed the bridge and consisted of tying a krokos, a ribbon of saffron color, around the right hand and the left leg of each mystes. This wen ton until the sunset, and then the pompe continued by torchlight. […] The second event took place on the bridge of the river Kephissos, where the initiates were harassed and insulted. […] Once the procession reached the sanctuary of Eleusis, Iakhos was received ceremoniously at the court. For the rest of the night the initiates sang and danced in honor fo the Goddess. The dances traditionally took place around the Kallichoron well and were meant to cheer the grieving goddess. […] Ont he following day (the twentieth of Boedromion) several sacrifices too place […] during the day the initiates fasted […] The fast came to an end with the drinking of the kykeon, the special potion of the Eleusinian Mysteries.” (18-19)

The Hegemon demonstrates that one need not suspend disbelief in atomic principles to enjoy the pleasure of the ritualism of the Mysteries. From textual fragments, Epíkouros enjoyed fellowship, celebration, procession, and self-reflection during these mystical ceremonies. Simultaneously, he rejected any literal interpretations of the mythic pageant. He may have appreciated the acknowledgement of change and the inevitability of death, while disregarding the proposition of the immortality of the human soul. Nonetheless, he participated in the rituals, including drinking kykeṓn, an allegedly god-manifesting sacrament.

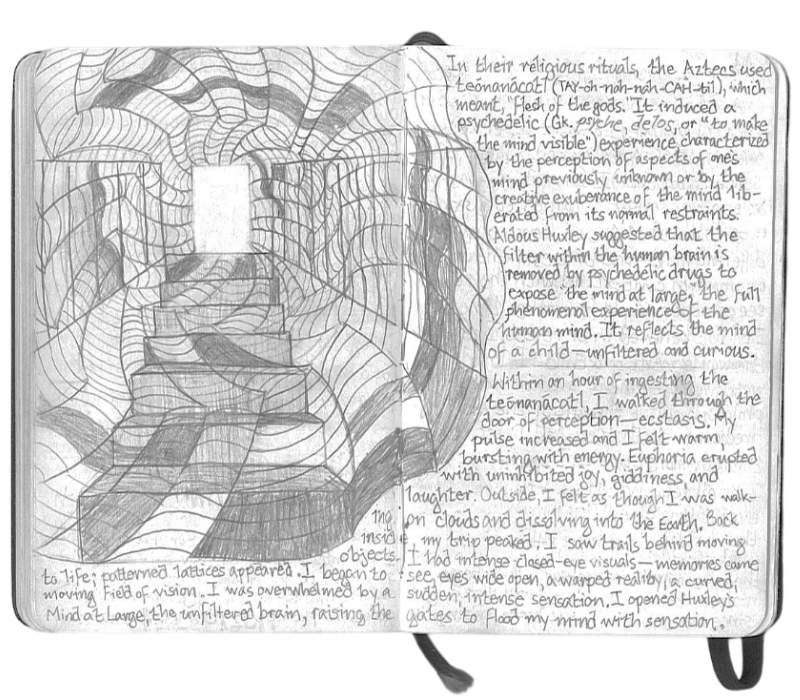

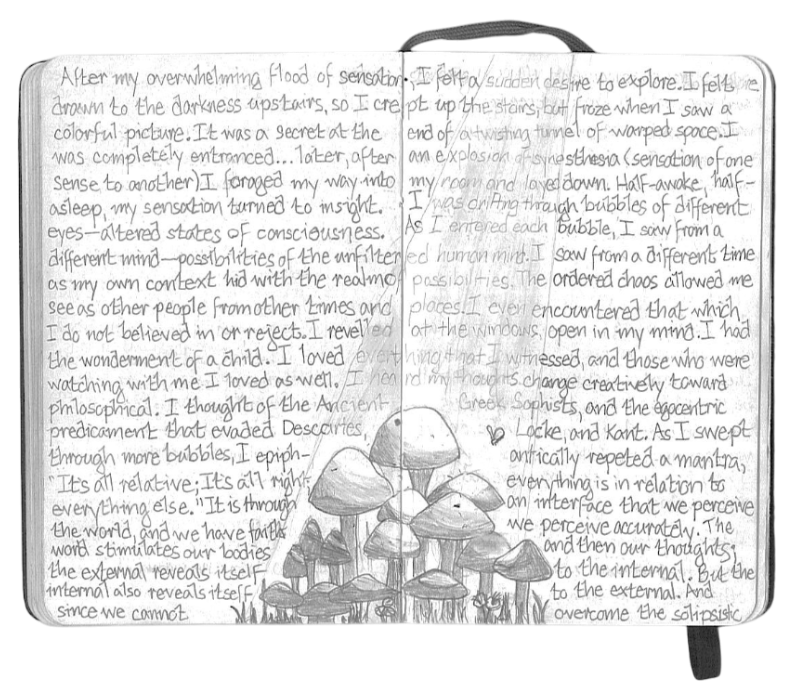

“Teonanacatl” from an unpublished diary (June 2009).

PART VI: THE SACRAMENT

Was Epíkouros tripping? Did his floor start rippling some 30 minutes after ingestion? Did tiny bits of light in the dark trigger complex, kaleidoscopic, visual geometric patterns?

Since the 1950s, a number of notable anthropologists, ethnobotanists, ethnomycologists, and chemists, including Albert Hoffman, who first synthesized the contemporary entheogen known as lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) have specifically presented the Greek sacrament of kykeōn used in Eleusian ceremonies as the chemical instigator that made the mind visible. ΚΥΚEΩΝ (κυκεών or kykeṓn) comes from the ancient Greek verb κυκάω (kūkáō) meaning “[it] stirs” or “[it] mixes”—it also carries the connotation of a mixture that “confuses” and “confounds”. Kykeṓn was thus employed when referring to a “potion”, “tonic”, “elixir”, or “mixed beverage”. We find a number of mentions of this substance in ancient texts.

In the Homeric Hymn to Dēmḗtēr, written between the 8th-and-7th-centuries BCE, the queen Metáneira “offered her [Demeter] a cup, having filled it with honey-sweet wine” (206):

Then she ordered her [Metáneira] to mix some barley and water

with delicate pennyroyal [mint], and to give her that potion to drink.

So she made the kukeôn and offered it to the goddess, just as she had ordered. (208-210)

The queen’s potion is accepted “for the sake of the ὅσια” or hósia, the “sacred” or “holy” rite whereupon a sacrifant initiates a “relationship” with the aforementioned deity wherein a supplication of χάρις (kháris) “thanks” or “grace” might be exchanged (211).

In The Iliad, “fair-tressed” Hekamḗdē mixes “a potion”. As further described:

Therein the woman, like to the goddesses, mixed a potion for them with

Pramnian wine, and on this she grated cheese of goat’s milk with

a brazen grater, and sprinkled thereover white barley meal;

and she bade them drink, when she had made ready the potion.

ἐν τῷ ῥά σφι κύκησε γυνὴ ἐϊκυῖα θεῇσιν

οἴνῳ Πραμνείῳ, ἐπὶ δ᾽ αἴγειον κνῆ τυρὸν

κνήστι χαλκείῃ, ἐπὶ δ᾽ ἄλφιτα λευκὰ πάλυνε,

πινέμεναι δ᾽ ἐκέλευσεν, ἐπεί ῥ᾽ ὥπλισσε κυκειῶ. (Iliás 11.638–641)

In The Odyssey, Hómeros describes “all the baneful wiles” of the goddess Kírkē, a vengeful sorceress who “will mix thee a potion, and cast drugs into the food…” (Odýsseia 10.289-290; Murray 1919). Before spiking the punch, she:

… made for them [a potion] of cheese and barley-meal and yellow honey

with Pramnian wine;

… σφιν τυρόν τε καὶ ἄλφιτα καὶ μέλι χλωρὸν

οἴνῳ Πραμνείῳ ἐκύκα· (Odýsseia 10.234-235)

The various kykeṓnes were composed “of mixtures” that usually included barley, cheese, and wine, but could also include, as is twice described by Hómeros in the foundational myths of the Hellenic people, an unknown adulterant. While the alcohol present in wine is known to produce mild states of euphoria and shades of bliss, it is utterly dissimilar to the intense, mystical dissolution that entheogens produce leading to visions of divine beings.

One compound to have been responsible for the psychedelic affects of kykeṓn was an active alkaloid from the ergot fungus Claviceps purpurea that produced visions, speechlessness, and euphoria (symptoms otherwise with religious ecstasy). At the Mas Castellar site in Girona, Spain, “Ergot sclerotia fragments were found inside a vase along with remains of beer and yeast, and within the dental calculus in a jaw of a 25-year- old man, providing evidence of their being chewed” (Juan-Stresserra 70). However, outside of sterile conditions, ingestion of the ergot fungus risks ergotism, a debilitating conditions caused by toxic molds. Raw ergot may have been unreliable in inducing desired visionary experience. Still, given the frequency of ingestion and the length of time over which this tradition was practiced, it is possible that, on occasion, proper chemical conditions could be facilitated to induce a euphoric visionary experience to orchestrate the myths of the Mysteries through the mycodegradation of barley or rye.

If ergot presents too much instability, opium is another candidate for a possible mystery sacrament: “It seems probable that the Great Mother Goddess who bore the names Rhea and Demeter, brought the poppy with her from her Cretan cult to Eleusis and it is almost certain that in the Cretan cult sphere opium was prepared from poppies” (Kerenyi 25). As Taylor-Perry describes, “there is ample iconographic and literary evidence linking poppy capsules not only with Demeter but also specifically with Eleusis” (121). A the same time, the sedating effects of opiates may not necessarily reflect the vivid experiences of psychedelia. Nonetheless, both induce a sense of euphoria and are have been demonstrated to stimulate hallucinations.

Ethnomycologists Valentine Pavlovna and Robert Gordon Wasson began fieldwork in 1956 on Mesoamerican rituals involving psilocybin mushrooms (Psilocybe mexicana) or teonanácatl, from the Nahuatl teotl (“god”) + nanácatl (“fungus”) — note the linguistic correspondence between teonanácatl and βρῶμα θεόν (brṓma theón), an ancient Greek reference to mushrooms, being the “food of the gods”. Wasson’s research later fueled speculations that these chemicals were ingested during rituals to commemorate the Eleusían Mysteries. They co-authored a The Road to Eleusis: Unveiling the Secret of the Mysteries with Albert Hofmann, a Swiss chemist — widely known for being the first person to synthesize and ingest lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) as well as isolating and synthesizing the principal component in psychedelic mushrooms, psilocybin and psilocin — who further reinforces these claims. In Food for Centaurs (1960) and The Greek Myths (1964), Robert Graves suggests that Amanita muscaria, the “fly agaric” mushroom was an added ingredient to the sacramental beverage. Terence McKenna makes a similar claim in Food of the Gods (1992). “The original cult of Dionysus almost certainly had its origins in the mushroom cults of ancient Crete” (Russell 103). “Among the Greeks mushrooms were apparently called” ‘food of the gods’ (broma theon), while the neoplatonic philosophy porphyry (ca. 233-309 CE) called them ‘nurslings of the gods’ (theotrophos)” (Russell 82).

Coherent with Epikouros’ approach of providing multiple explanations for unusual phenomena, I would like to share the following proposition: whether ergot, or poppy, or mushrooms, or wine infused with psychoactive mints, the insistence of Epíkouros on participating in the Mysteries is a reflection of his recognizing the pleasurable feeling associated with ingesting psychedelics. One of the most identifiable symptoms of the psychedelic experience are complex visual forms, kaleidoscopic shapes, intricate geometric lattices, patterned space, multi-textured surfaces, shifting contours, oscillating color, and complex entities — these visual images are deeply impressive, and considering the results of Timothy Leary’s Marsh Chapel Experiment, the anticipation one possesses of communing with a deity, when under the influence of psychedelics, seems to reliably produce the internal perception that a deity or divine state is present.

We should keep in mind that Epíkouros recommends restraint and sobriety as the rule and cautions against indulgence. Epíkouros dismisses “Bacchant revelers” as those who “rave like lunatics”, indicating a balanced approach with respect to intoxicants, composed yet compelled, rational yet enthusiastic (Philodemus, On Piety, Col. 19.9-12). Given the sacrament that would have been featured in the Mysteries was psychoactive (at least with wine), it would be historically anomalous for an Athenian who participated in the Mysteries to have been unfamiliar with altered states. It would have been even stranger for a person to have found no correspondence between the sacrament, the cult, and the mystical experience. The ubiquity with which entheogens have been documented through the ancient world leads me to believe, quite simply, that ancient Epicureans liked tripping as much as the rest of us.

PART VII: FUN GUYS

You won’t see me at Sunday School, but I do share in most of the “traditional festivals and sacrifices” of our society. I practice remembrance on Memorial Day and exercise gratitude on Thanksgiving. I enjoy the festivities of St. Patrick’s Day and liberation on Cinco de Mayo. I find Día de los Muertos to be beautiful, and compelling, and I will never stop dressing-up for Halloween. I extend kindness and generosity in the name of patrons like Lady Liberty and Father Christmas. I support local Spring fringe festivals and the artists who host them, who explore the breadth of the human soul on-stage, and induce a communal catharsis. We further celebrate Thespis, ancient patron of theatre. You might even find me in a dark room, listening to Pink Floyd, having ingested fungus to induce the same state as did Greek mystics thousands of years ago.

None of these activities require our suspension of disbelief in mythical characters or genuine enthrallment with political propaganda. It’s a blessing to spend time with friends, regardless of the reason. I enjoy decorating a Christmas tree without indulging the nativity myth. I find the darkness and the candles of midnight mass to be beautiful, even if the rest of the program disgusts me. Springtime feels naturally rejuvenating, and I mean to celebrate it, but I feel no need to complicate that pleasure by mythologizing seasonal necromancy. Prayer, meditation, contemplation, and confession each provide practical utility in the form of psychological healing. That measurable healing that reliably occurs supersedes any superpowers supposed to be available. The true “secret” of “the secret of the Mysteries” is that mysticism itself is a totally-natural phenomena. It is repeatable, measurable, and, by-definition, literally manifest to the mind’s eye. The Mysteries represent a “fantastic mental application”, analogous to a waking dream, that can be used like a tool to induce the same visionary experiences that have been documented in nearly every wisdom tradition on the planet, both esoteric and institutional.

Like Epíkouros, I reject taking the myths of my own culture literally … otherwise, one could be lead to think that God is measurably weak, having failed to stop the escalation of authoritarian regimes … and every mass act of violence in my adult life. Like Epíkouros, I express particular frustration with any practices that target the finances of needy people, so astrology, in particular, is fraudulently detestable (nonetheless, the same, useless form that failed to provide meaningful answers 2,330 years ago). Whether it is 305 BCE or 2025 CE, history records the masses of human beings searching for answers in all of the wrong places. A robust, philosophical system is required to ground an individual against the confusion and turmoil of cultural insanity, and provide them with psychological tools to confront the universal fear of death. Even when immersed in a society defined by science and technology, the masses continue to revert to superstitious myths, even despite a dozen-or-so years of education.

For this reason, a material description of the religious experience is a requirement. Without a standard of knowledge, the difference between inspiration and delusion is relative. Without a standard based in nature, all propositions are merely temporary speculations. The symptoms of spirituality, used irresponsibly, can be exploited to reinforce false mythologies. When used properly, it unleashes the mind at large and allows one to interface with the full symphony of nature, overcoming the myths that are created by our misunderstandings.

Centuries of critics have been categorically wrong in charging against Epicureans that “we deprive good and just men of the fine expectations which they have of the gods sincere and sonorous prayers” simply because we reject mythic expressions of religious faith that are incoherent, dangerous, emotionally-immature, and psychologically-irresponsible (On Piety Col. 49.19-25). We reject cosmic narcissists, holy puppeteers, ghostly voyeurs, and divine strategists. The existence of any of these mythic super-beings would imply that a supernatural force every day fails to prevent inexhaustible violence — or else, it means that our lives are so utterly meaningless that inexhaustible violence is insignificant on a theological scale — here lies the danger against which Epíkouros warned: the representation of “God” spread by many today is capricious, partisan, and despotic. In this regard, many popular conceptions of “God” do not meet the Epicurean qualification for a truly blessed being. When presented as a crusader, a chess master, a politician, or a monarch, “God” seems more like a monster, more like an ancient trickster of tragic poets than a divine icon of blessedness. Like those tragic poets, the authors who incite these conceptions combine multiple, unrelated preconceptions together to form paradoxical divinities who cause trouble and suffer pain — and they profit from it. The mythic texts of frauds are filled with examples of “gods” behaving badly. We do not hold these chimeras to be gods.

After my psychedelic experience, I am compelled to defend piety, especially against those who would pervert it into a political narrative or a pyramid scheme. “Spirituality” has been appropriated, and those who have appropriated it risk alienating many of us who wrestle with genuine turmoil, and have been disenchanted by myths: Belief in an ever-present spirit will not calm someone suffering from paranoia. Faith in an otherworld will not reassure someone suffering from suicidal ideation. In my state of psychedelic euphoria, the immediacy of life and death was manifest, and the importance of making the most of the only time I have became immanently clear. The significance of kindness and the value of friendship became central. The smallness of prejudice and the breadth of the universe was embodied. I became conspicuously aware of the uselessness of rage and the blessing of tranquility. That mystical experience triggered by a handful of mushrooms cleansed my mind and reaffirmed a commitment to pursue true happiness.

Doubt me if you will!

… but eat 4 grams of blue meanies, I promise … I promise, the obviousness of the relationship between entheogens and the prehistoric formation of religion will become immanently clear. (Use responsibly). Now, if I might make a final recommendation:

Turn onto philosophy, tune into nature, and drop out of myth.

Your Friend,

EIKADISTES

Keeper of Twentiers.com

Editor of the Hedonicon

“The Aquarium” from an unpublished diary (June 2009)

Works Cited

Bartman, N. H . “The Life of Epíkouros: A Translation for Twentiers.” Academia.Edu, Leaping Pig Publishing, 21 May 2025, www.academia.edu/129436319/The_Life_of_Ep%C3%ADkouros_A_Translation_for_Twentiers.

Bennett, J. W., and Ronald Bentley. “Pride and prejudice: The story of ergot.” Perspectives in Biology and Medicine, vol. 42, no. 3, Mar. 1999, pp. 333–355, https://doi.org/10.1353/pbm.1999.0026.

Davis, Gregson. A Companion to Horace. Blackwell, 2010.

Chilton, C. W. Diogenes of Oenoanda: The Fragments. A Translation and Commentary. Published for the University of Hull by Oxford University Press, 1971.

Clay, Diskin. Paradosis and Survival: Three Chapters in the History of Epicurean Philosophy. University of Michigan Press, 2001.

Cicero, Marcus Tullius, et al. Cicero on the Nature of the Gods. 1872.

Cosmopoulos, Michael B. Bronze Age Eleusis and the Origins of the Eleusinian Mysteries. Cambridge University Press, 2015.

Dēmḗtrios of Lakonía. “On the Form of God.” Translated by N. H. Bartman, Twentiers, 5 Apr. 2025, twentiers.com/form-of-god/.

Diogénēs, and Martin Ferguson Smith. Supplement to Diogenes of Oinoanda the Epicurean Inscription. Bibliopolis, 2003.

Empiricus, Sextus. Against the Physicists. Against the Ethicists. Translated by Robert Gregg Bury, Heinemann : Harvard University Press, 1953.

Empiricus, Sextus. Outline of Pyrrhonism. Translated by Robert Gregg Bury, Harvard University Press, 1990,

Encyclopædia Britannica, 9th ed., vol. 2, Adam & Charles Black, 1875-1889.