From time to time I remember our philologist at high school who always insisted on the alliteration of letter “B”. Whenever a student was unprepared our good professor never stopped saying “You are blind in your ears, blind in your mind and blind in your eyes.”

It took me many years to listen to Thanasis Veggos in a Greek black-and-white movie saying: “My grandmother is a happy person. She neither sees, nor hears …”

It took me even more years to come across the Delphic precept: “Aitio paronta” (to find the causes of what is happening now).

And more years should pass until I understood why modern Greeks, Graikoi and Romioi feel ashamed rather than sorry for the degradation of their country.

And after all these years of melancholy I met Epicurus, who took me by the hand and walked me in all those difficult paths that bypass the misery of alliteration of letter “B” and lead to “well-being”.

Then I realized what our good professor was trying to say. He briefly wanted to say: “It is good to philosophize about life but it is better to philosophize in life.”

More or less he wanted to say that in order to philosophize in life, to defend your dignity, to live happily every day of the rest of your life, help your neighbor in difficulties you must have your eyes and ears and your mind open and observe carefully what is happening around you and find multiple causes (“Aitio paronta”).

He wanted to say that in order to win your happiness in this unprecedented phenomenon called life you must learn to observe the world outside and inside you with open eyes and mind that knows how to think.

He also wanted to say that the Greek always relied on observation with eyes and mind wide open, which leads to discovery, and not with mind and eyes closed -which brings the intellectual laziness of the Apocalypse.

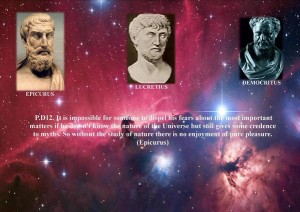

Epicurus, who was widely read in his era, certainly knew this alliteration of his Greek grandfather Sophocles and even if he did not, he definitely carried it inside him because he was Greek above all and as a Greek he was talking through Diogenes Laertes’s¹ lips: “However, someone cannot become wise regardless of his physical condition or national origins.”

Clement of Alexandria² says the same, making his comment about Epicurus: “Epicurus on the contrary considers that only the Greek can philosophize.”

But Epicurus himself in his speech will say³: “In your old age you are the person that I advised you to become. And you know how to discern what it means for someone to philosophize about oneself and what about Greece. I am pleased with you.”

We mentioned the above to emphasize the consciousness of Epicurus’s ethnic origin for the simple reason that the great humanists and enlighteners who rebirthed Europe and the world were Greeks.

This is not because we are some chosen nation but because the Greeks cultivated the field of logic while other nations cultivated the field of faith and illogical emotions.

In the years of Epicurus, the city–state is falling apart, the religion of the city is unable to provide answers and while the social recognition was measured only with gold, Epicurus himself, carrying the values of his Greek grandfather, measured the social prestige with the radishes of his garden, not because he was frugal but because he wanted -as he used to say- to be free.

So, Epicurus not only did not forget that he was Greek in those times of great subversion of the values of the city-state but he also kept what he could keep from his Greek grandfather’s legacy. Because he knew that what we have is not what they have given to us but what we have managed to preserve.

Perhaps Epicurus was a little lucky. As a starting point he used the Pericles’ Funeral Oration. Modern Greek people are confused between the Pericles’ Funeral Oration and the Psalm of the Byzantine Roman Emperor.

I mean that this irreconcilable contradiction between two value systems, the ancient Greek and the Byzantine Christian, where the first calls you to open your eyes and look up and the other one invites you to close your eyes and your mind and kneel low, makes modern Greek people what the film director Marangos calls “Black Baaa”, the “Black sheep”.

Why cannot somebody look at the Pericles’ Funeral Oration and at the Byzantine theocracy simultaneously? You squint! And when you squint things seem wrong and only knowledge, the result of open eyes, ears and mind can help you see the path of your life in accordance with the values that you keep.

The vulgar argument of Dostoyevsky “If God did not exist everything would be permitted”, means that all the punks would do anything they want, goes back to at least Plato. Epicurus answers with his own views on justice, not copied from a previous philosopher but written by his own experience from his very own root taken from the function of the Greek city-state, which has been filtered through his open mind, through his open eyes and through his open ears.

I mean that in the city-state, where citizens realized very early that the laws do not come from outside, from some higher authority figure, whether it is called God, or Moody’s Credit Rating Agency, the citizens themselves were interested in making laws and respect them in order not to harm and not to be harmed.

In those times, the Hellenistic period, Epicurus very early realized that there is no hope that life will come here since the laws came from there, from very far away.

However, not to have hope does not mean that you are desperate, and when you realise that you are not hemmed in a framework but in a context of readiness, you feel liberated so you can redirect your energy in creation and not in the system, which of course is at fault, but we keep feeding it.

The creativity of Epicurus that we are talking about is initially expressed with the creation of the Garden. He wants to make a society inside the society of the Hellenistic period. Laws that came from far away concerned the society of people living in and with the present. The participants themselves will make the rules and “laws” within the Garden and the rules would apply forever and not only in the present. It was a sense of justice which surrounded him.

You see, the thoughts of Epicurus were not about the present but about a different context. He drew a huge amount of information from the tradition and the past and transformed this information into judgments and reasoning about the future. And this means that the thoughts of Epicurus were not about the individual but about the kind called “Human” which means that his thoughts were in humanity. In other words, Epicurus resided in the Garden but he lived all around Greece and he embraced it, not to mention the rest of the world. His letters confirm this.

Epicurus was not for only himself. Epicurus is dealing with humanity. His loneliness was the womb of production of his work. Otherwise, one works and does not produce anything with a universal character. In other words, Epicurus in his garden read the dead and wrote for the unborn.

Living all over Greece he kept realizing that “exist” means “coexist”.

The founding of the Garden was an expression of another value which comes from the values of the city–state. In the Garden he could accomplish the splicing of two concepts, the concept of the foreign and the concept of friendship, to create the highest value of hospitality that characterizes the world of the Greek city-state.

Outside the Garden the stranger may have been a slave or a free citizen, man or woman, housewife or courtesan, rich or poor or whatever. Inside the Garden he was his friend.

In the Garden Epicurus in reality was treating a being, the human being. His project was not “humanitarian”. A humanitarian project treats a lack, not a being. A “humanitarian project” is political, charitable and about usury. Epicurus’ project was about enlightenment and humanism. He treated the human existence.

With open eyes and ears and mind (to quote again the alliteration of “B”) he did not just see. He was looking. He was looking not at what acted but at what existed. He was looking at the human.

In the Garden, not everyone could find a setting for the supernatural type of “salvation,” but an environment capable of neutralizing the alliteration of “B”. An environment where everyone would not do what had to be done but what was right to do. And the right thing to do has no relation with principles but with values.

So the humanism of Epicurus is not only expressed through his interest in human existence, nor in the value of co-existence. It is neither expressed through the value of hospitality, nor the value of friendship and the sense of equity, that is to say all that were mentioned above.

The Humanism of Epicurus is expressed by what is deeply ingrained in our Greek national consciousness, which is associated with the context of values and not with the context of principles. Because as you know, these systems of principles are always related with the current moral systems, which are transforming from place to place and from time to time. Therefore the system of principles come and waive.

The system of morality, which was prevailing in Greece during the Hellenistic period, left Epicurus coldly indifferent. That is why he decided to do the deviation from his social duty, which claimed the freeborn to be with the freeborn, the slaves with the slave sand the women in a strictly male-dominated society to be mistresses and wives, but confined to the home. He deviates from a social duty because he knows that the task derives from a social morality that may not apply tomorrow. Epicurus looked way ahead of tomorrow.

That’s why the Garden, which was working with values, was open to everyone: for freeborn, for slaves and for men and women, rich and poor, in stark contrast with the existing system of social ethics. For that reason he was accused of being immoral.

Carrying the heavy load of Hellenism inside him, he is moving within a framework of values, such as those of freedom, friendship, sacrifice, debt, patriotism and historical memory. Because the values in contrast to the principles have to do with utility, time does not touch them.

The principles have to do with the individual. I have a principle not to lie or not to usurp the things of others. I have a principle not to lend and not to borrow, etc.

There is something more. Values are related not only to reaction but to resistance as well. Epicurus resists a mass society and founds the Garden a society of people who think with open eyes, open ears and open mind. That is how Epicurus, the great Teacher and Humanist who was aware of his enlightening mission, envisioned human society.

In other words, Epicurus is a man different from what every person of authority would want but as the nature wishes a human to be, that is to say a person with intelligence and altruism. That is why Epicurus differentiates himself from the people who make up the society of his era, the mass society and by making himself a human he now belongs to society.

That is why he puts aside his social duty, in other words the prevalent social principles. Because he knows that the societies of people live according to principles. Humanity lives according to values.

With the diversion from his social duty, which is led by a temporary social morality and with the expressed parameter of the Epicurean virtue of self-sufficiency, Epicurus declares himself free and remains stable to his values, one of them being the value of freedom. He wishes to offer this freedom to the people. That is why his students and Lucretius, Torquatus and Velleius and also the sceptic Lucian call him “liberator”. He is a liberator. He sees the people of his era who have become slaves, not only financially but politically, socially, and particularly mentally. Epicurus tries to liberate the enslaved mind of the Humans of his era.

Now we can better understand the Epicurean beliefs about the Divine, another expression of his Humanism and his enlightened speech, as he extricates the humans from the fear of God and the agony of death. By observing the society of his era, Epicurus concludes that if Gods were interested in mankind or if they loved it, they would commit suicide. He expresses the opinion that Gods do not care for what is human, and at the same time by studying human nature, he understands how attractive rituals are for people and he does not hesitate to motivate his friends to take part in them. On the one hand, he dislodges every clergy by deducting any supernatural powers which are attributed to Divine and on the other hand he does not deny human nature and human adrenaline.

The “Liberator” Epicurus renders an ideal type of behavior through the centuries and he does that with his humanism and his enlightened speech and work.

He is the only one who talks about happiness in this unprecedented phenomenon called life, and any kind of happiness is up to us.

Nobody talks about that, neither the stoic nor the sceptic or the cynic. Nevertheless, if and when they talk about happiness, they place it in a supernatural or utopic field far away from the everyday person.

The Epicurean type does not stick to nostalgia but proceeds to action as he considers that happiness depends on him. That is why Epicureanism is a philosophy of action. It is an action of enlightenment capable of opening the eyes, the ears and the mind of other people. It is an action related to human freedom as the highest value and not as a social morality or duty.

Notes

1. Diogenes Laertes X. 117 (226 Us, 1.117), from the book of George Zografidis: “Epicurus Ethics: The Therapy of the Soul”, pg 483, Zitros Publications

2. Clement of Alexandria: The Stromata 1.15.67 (226 Us 143), from the book of George Zografidis: “Epicurus Ethics: The Therapy if the Soul”, pg386, Zitros Publications

3. The Sayings of Epicurus 76, from the book of George Zografidis: “Epicurus Ethics: The Therapy of the Soul”, pg 322, Zitros Publications

4. The Sayings of Epicurus LXXVI. In 1888 C. WOTKE discovered the collection “The Sayings of Epicurus” in the Vatican among the manuscripts of “Codex Vaticanus Graecus”. This collection contains some of the Principle Doctrines which are noted as K.D.

By Dimitris Dimitriadis, from the Epicurean Garden of Alexandroupolis

Tweet This