“For people lose all appearance of mortality by living in the midst of immortal goods (athanatoi agathoi).” – Epicurus in his Epistle to Menoeceus

“I’ll think of you as an immortal, and you think of us as immortals!” – Epicurus, to Colotes

As we continue our deliberations about the meleta portion of the Epistle to Menoeceus (about which I’ve already written two essays here and here), the concept of “immortal goods” has come up for deepening.

Furthermore, the passage links the immortal goods to the “surroundings” or “ambience” of someone who is living a godlike lifestyle. This is because the life state of each sentient being is contextual to its environment. What are the surroundings of one who lives like an immortal?

Friends as Immortal Goods

The first and least controversial item that belongs in the official list of immortal goods is our friends. We know this with certainty because:

The noble soul occupies itself with wisdom and friendship; of these the one is a mortal good, the other immortal. – Epicurean Saying 78

VS 78 says that friendship is immortal, and wisdom is not. Therefore, in our sources, friends are the only thing that are clearly included among the “immortal goods” mentioned in the Epistle to Menoeceus, and each one of our true friends may therefore serve as a case study to better understand the doctrine of immortal goods.

So following this interpretation, we live like gods if we are surrounded by our friends, each of whom is an immortal good, and we should treat our Epicurean true friends as immortal goods–so long as we remember them with gratitude, they ARE part of us and, in some way, immortal.

Worthy of Immortal Life

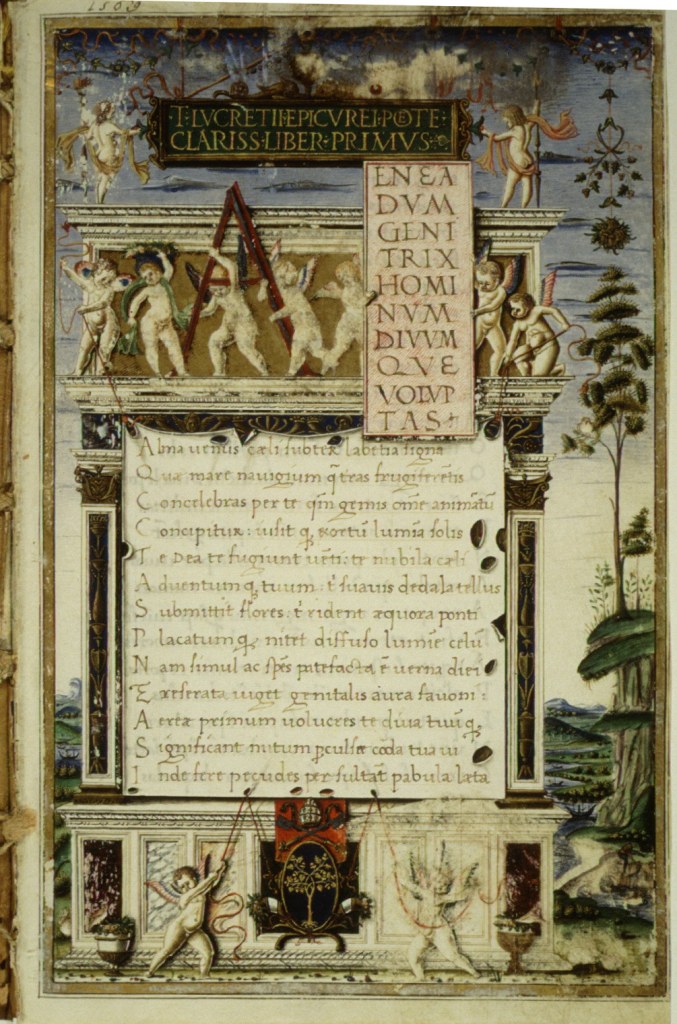

The idea of “Athanatoi agathoi” is expressed differently in De rerum Natura. Rather than say there are eternal goods, Lucretius mentions that some things are or aren’t “worthy of immortality“, attaching an “immortal quality” to the worth or value of the thing it describes, as if there was a transcendental quality that makes some things have more value than others.

Philodemus also laments that people give worship to things that are not at all “worthy of immortality and blessedness”. It’s clear that, to the Epicurean Guides throughout history, the Doctrine of Immortal Goods has served as an invitation to deliberate about what things are worthy of immortality, and to deliberate about values. What do you think is worthy of immortality?

If each one of our true friends is, to us, either “worthy of immortal life” or an immortal good (“athanatois agathois“), and if we wish to place before our eyes the ways in which our truest friends are immortal, we should consider what makes them our closest friends. What advantages and pleasures do we share with them? The two undeniable attributes of the Epicurean gods in our writings are invulnerability and bliss: how do our friends contribute to this?

The Pleasures and Fearlessness of the Gods

When I asked about possible interpretations of “athanatoi agathoi” in the Garden group on FB, one of the members (Beryl) said: “I saw this phrase as pertaining to the letter as a whole as meaning (that) when one has rooted out fear of death then it’s as if one is immortal. When one has understanding of nature, one can simply (be) satisfied so as to enjoy life with no suffering as if one is immortal. When one has retired from the hurley-burley of the throng or understands one’s true reasons for involvement, one’s mind is peaceful even amongst storms like an immortal being. I thought the important word is appearance. Folk are still mortal, however, releasing fear and creating an ease full path for satisfying one’s necessary needs gives the peace of mind of an immortal.”

So in this interpretation of “immortal goods”, it’s the mental state and the existential achievement of calm and tranquil abiding that gives mortals the appearance of godliness.

The Theory of Pleasant Remembrance

In Epicurean ethics, visualization (the “placing before the eyes” exercise) and the use of happy memories (the “pleasant remembrance” exercise) are useful ethical practices. The full theory behind them is beyond the scope of this essay, but it is clear that memory plays an important part in how we practice them.

One way to unpack why true friends are considered “immortal” is to think that they are sources of ongoing bliss and pleasure, at least for as long as we remain grateful and remember them. In fact, any object of enjoyment that we practice “pleasant remembrance” with is, to some extent, experienced as immortal or undying.

Experiences and friends around whom we have built pleasant memories are, by definition, memorable, and since the pleasure continues for as long as we are grateful, they are in some way “immortal goods”.

Once we have carried out the exercise of placing before our eyes our friends and the ways in which they are immortal, we may consider other possibly immortal goods–for instance, the Doctrines of true philosophy, or the Four Sisters mentioned in PD 5. Reasons to include them among the “immortal goods” have been sufficiently expounded in our reasonings and video about PD 5. They are important points of reference in our ethics, and in our expectations of each other and our social contract–and since the LM mentions that these “immortal goods” must be a feature of our surroundings, and it’s hard to imagine a godlike lifestyle without them, The Four Sisters (Pleasure, Nobility, Justice, Prudence) must also be “athanatoi agathoi“.

If we apply this criterion of “memorability” to the immortal goods, we must also recognize that practices that produce blissful or pleasant states (even if not anchored in a past memory) can also be counted among the immortal goods if they have a similar transcendental quality as our remembered pleasures. I would argue that anything that helps us to feel fresh pleasures without fail (whether it is yoga, exercise, laughter practice, etc.) can also be counted among our immortal goods for a long as the enjoyment persists.

If Wisdom Dies …

We must also consider why wisdom (sophia) is mortal–but not phronesis (“practical wisdom”)–while friendship is immortal, as per VS 78. If Wisdom dies, if she’s not immortal, this is an interesting philosophical statement.

It may be that the statement that Wisdom is mortal is meant to diminish our sense of pride in our intellectual achievement, and to cure the pedantry that is often part of how other schools practice philosophy.

Might it also be that knowledge (or wisdom) does not produce the memorable feeling of pleasure that friends and salient experiences produce? Maybe this refers to cognitive decay: our brain’s abilities decay as we age, so that wisdom is seen to fade. If the first is the case, then the “memorable” criterion for things that are “immortal goods”, or at least “worthy of immortality”, is accurate.

Furthermore, we must consider Lucretius’ passage that calls the Doctrines of Epicurus “golden, and worthy of immortal life” in light of these considerations. It seems like he, at least, considered the words of true philosophy (epitomized in Epicurus’ Doctrines) to be among the immortal goods, incarnations or instances of phronesis (practical wisdom).

Memorable Experiences and our Hedonic Regimen

If memorable experiences are what characterizes immortal goods, then we may survey what memorable experiences we carry in our souls, so as to cultivate them. If it is true friends, then we may seek them out. If it’s the virtues mentioned in PD 5, then we may seek to find orientation in our choices and avoidances so as to ensure the presence of those virtues in our environment.

What goods do we consider worthy of immortality? How do we gain a godlike appearance, or create a godlike lifestyle and godlike surroundings? And, finally, how can we plan our life so as to live surrounded by immortal goods? These are some of the questions that may help us to gain clarity concerning the “athanatoi agathoi“. Of course, these considerations are meant to bear on our choices and rejections, so that we may swerve in the direction of these immortal goods.

I’ve had the pleasure of reading Copley’s translation of De Rerum natura (

I’ve had the pleasure of reading Copley’s translation of De Rerum natura (