Book 11

This book rejects the idea that the Earth is the center of the cosmos, and discusses objects that float in the air. It says “certain people conceive Earth circled by walls … and suppose that Earth is in the center of everything“. Now, since Epicurus believed the universe was infinite, we know that he would have rejected the Earth-centered model because an infinite model of cosmos would not have a center and all things would be relative to each other. Instead, there would have to be innumerable “centers” or hubs. Epicurus had to use the language available to the ancients to explain what orbits are–and the organized dance between many orbiting bodies that acquires a certain balance of pushing and pulling and falling–without having the word “orbit” available.

Epicurus discusses where the sun rises and sets, and its distance from us; He offers various models to interpret this.

Les Epicuriens commentators categorize this book as a polemic against the ancient astronomers who were using certain tools or machines (alluded to in this book) to evaluate the movements of celestial objects, and against Eudoxus’ geocentric model. I found this article about Eudoxus of Cnidus, which says:

An astronomer named Eudoxus created the first model of a geocentric universe around 380 B.C. Eudoxus designed his model of the universe as a series of cosmic spheres containing the stars, the sun, and the moon all built around the Earth at its center. Unfortunately, as the Greeks continued to explore the motion of the sun, the moon, and the other planets, it became increasingly apparent that their geocentric models could not accurately nor easily predict the motion of the other planets.

The next section of the 11th book is on what sustains Earth from below and seeks to explain its stability. Epicurus argued that densities below and above provide counter-balance to each other, to maintain the “appropriate analogical model” for the immobility of Earth. He said that the Earth was “equidistant to all the sides”, and so it didn’t fall in any direction because it had similar pressure from all sides.

Here, from Epicurus’ mention of an “appropriate analogical model”–which he presumably was trying to create–it is clear that he was using the Epicurean method of looking at the things that can be observed and reasoning by analogy about the things that are beyond our observable horizon. This means that he appealed to how we can see that things of similar weight balance each other, and he’s applying that logic to the orbit of the Earth.

Book 12

This book addresses eclipses. Also, according to Philodemus, in book 12 (in a passage that did not survive) Epicurus said that humans had the idea of “certain imperishable natures”. This book appears to also address theology.

We see that in On Nature, Epicurus is addressing phenomena that caused superstitious fear and panic in the ancients, or that inspired mythical explanations. Obviously, the orbits of the sun and moon were a mystery and inspired mythical explanations. Epicurus’ lectures were meant to impress upon the students that, by applying their faculty of empirical reasoning to the study of nature, they would be able to come up with reasonable alternative theories.

We can surmise that some ancients, particularly those who rejected the myths and observed nature, would have observed that eclipses and phases of the moon apparently showed the shadow of the Earth against the moon, and would have reasoned that the Earth was round from the observation of its shadow against the moon. This is not mentioned in what remains of this book, but it would have been consistent with the Epicurean method (which relied on referring all investigations the study and observation of nature) to conclude from the phases of the moon that the Earth was round.

Book 13

This book seems to continue the conversations about gods in the previous book. Philodemus says that here, Epicurus addressed the “rapports of affinity, and also of hostility, that gods have with certain persons“.

Book 14

Based on the condensation of water (which can be seen turning into a gas/vapor, and also into solid ice), some ancient philosophers said that it can be inferred that all things come from a single substance, which changes due to condensation and rarefaction. Some philosophers believed the single primal substance was water (that is, all things could be broken down into water).

Epicurus’ refutation of this theory and his own alternate explanation is incomplete and unclear in the portions that remain of this book. We see him further down discussing the vaporization of water. Centuries later, Lucretius (in On the Nature of Things, Book IV) would describe in accurate detail the cycles of rain and condensation in one of the most brilliant passages of his epic poem. It is clear that these considerations furnished crucial inspiration for the early atomic theory.

The lecture in Book 14 was against monism–the above-cited doctrine that all things are ultimately made up of one single substance. Anaximenes and Diogenes of Apollonia were monists who said the primal substance was “air”, not water.

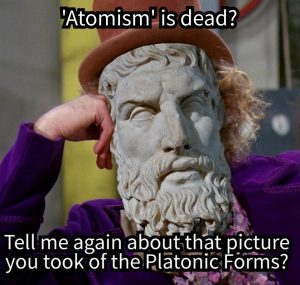

Epicurus discusses fire, and criticizes Plato’s Timaeus, saying Plato’s and other theories are based on faulty deduction. Epicurus reduces Plato’s physical theory to its absurd contradictions. For instance, he seems to be arguing that if things are really made of Platonic forms (like triangles, etc.), rather than from the atomists’ primal elements (that is, particles), then why are there no physicists creating new chemical combinations out of these Platonic triangles and circles? Here, he was acting in the tradition of the laughing philosophers. In Swinish Herds and Pastafarians: Comedy as an Ideological Weapon, I wrote:

Democritus, the precursor of Epicurus … was known as the “Laughing Philosopher” for making cheerfulness his key virtue and for the way in which he mocked human behavior. The tradition of the laughing philosophers had to start with the first atomist: materialism liberates us from unfounded beliefs to such an extent that it renders absurd the beliefs and the credulity of the mobs.

This book concludes with a portion that studies the differences between a sage and a compiler, saying that they are quite different. Epicurus tackles the issue of borrowing from other thinkers and mixing up disparate theories that are not coherent with each other. He says that sages do not praise both theories when they cite two opposite opinions. He accuses those who mix incoherent doctrines of “doctrinal solecism“, and indirectly criticizes the rhetors who are fond of empty praise.

A Note on Striking Blows for Epicurus

On Nature makes it clear that Epicureanism was born, and evolved, as a series of polemics. The first Epicureans enjoyed polemics. They relished opportunities to tackle intellectual challenges using their philosophical methods. Almost all of Epicurus’ points in this series of lectures are polemics written against someone else’s theories which are found to be wrong, and we also see many of Philodemus’ works were as well. For instance, we see Theophrastus being cited in Peri Oikonomias (and other works) as a source that the Epicureans of the FIrst Century BCE wrote against and commented on. We must conclude that he was considered a worthy opponent and a philosopher worth reading by them.

Therefore, we can imagine that it’s difficult to understand these arguments clearly without understanding these other ideas that they are refuting. Students of Epicurus must understand his contemporary thinkers, whose works they were reading and commenting on.

Further Reading: