Happy Eikas and Welcome to year 2,366 of Epicurus! Today we celebrate the birth of Epicurus according to Hellenion.org’s Attic calendar and also the Gregorian calendar (because his birthday coincides in both this year).

Literary Updates:

November 2024 Eikas – Theoxenia: a Practice of Epicurean Hospitality

December 2024 Eikas – Nature Must Not Be Forced

Epicurean Gamikós (“Matrimonial”) Script – our friend Nate gives a version of Epicurean liturgical guidelines for a wedding ceremony. This reminded me of an essay I wrote many moons ago titled An Epicurean Approach to Secularizing Rites of Passage, where I argue that we are able to preserve the utility of ceremony while purging it from supernatural claims by articulating the benefit of the ceremony in terms of social contract

In this essay, I will evaluate Epicurean soteriology in Lucretius by surveying the five Lucretian hymns to the Hegemon and looking for themes and patterns in them.

The Five Lucretian Hymns to the Hegemon

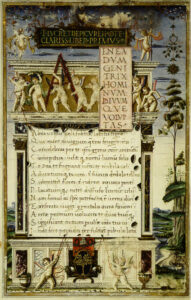

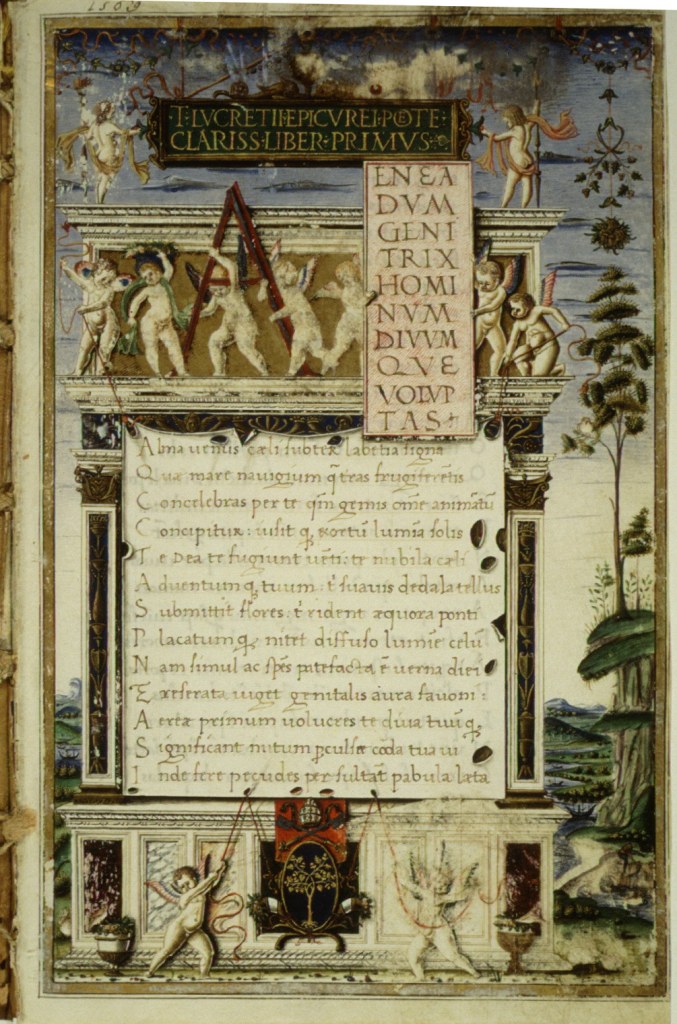

Liber Primvs

In verses 61-79 of the first book by Lucretius, we first see a Promethean depiction of Epicurus as Liberator from the oppression of religion, whose terrors spark an angry zest in the Hegemon. He is hailed as a “conqueror” who gained the secrets of the study of nature for the benefit of mortals, and who

reports

What things can rise to being, what cannot,

And by what law to each its scope prescribed,

Its boundary stone that clings so deep in Time.

Wherefore Religion now is under foot,

And us his victory now exalts to heaven.

These last two verses are often quoted as part of the “mysteries” related to the meleta portion of Epicurus’ Epistle to Menoeceus, where Epicurus says we will live like immortals if we practice philosophy correctly. The verses in Latin are:

quare religio pedibus

subiecta vicissim opteritur,

nos exaequat victoria caelo.

The poem from Liber Primvs precedes the tale of Iphianassa, who was sacrificed by her own father to the Goddess Diana, so that part of the context of this initial poem (as I discussed in Mahsa Amini: the new Iphianassa) is that religion cannot be trusted to provide a social contract or a sense of morality or right, and that (as our third Scholarch Polystratus argued adamantly in one of his scrolls) without the scientific study of nature, our pursuit of these things is in vain.

The Iphianassa portion closes with a formula that is often used by modern Epicureans online whenever they create memes to criticize religious tyranny: tantum religio potuit suadere malorum, which translates as “so much of evil could religion prompt”.

Liber Tertivs

Liber Secvndvs does not have an opening poem in praise of Epicurus. Instead, it praises the salvific power of philosophy when it invites us to the study of nature so that we will not be trembling in fear of the unknown and speaks to us of the well-walled fortress of the wise (templa sapientorum).

In the first verse of Liber Tertivs, we continue to see the juxtaposition of darkness (tenebris) and light (lumen), which we also encountered in Liber Secvndvs, which paints Epicurus as a figure of Enlightenment. This is one of the recurrent themes in Lucretian hymns: the battle between darkness or ignorance and light or wisdom. The poem later refers to Epicurus as the fatherly Founder of the School in this way:

Our father thou,

And finder-out of truth, and thou to us

Suppliest a father’s precepts; and from out

Those scriven leaves of thine, renowned soul

(Like bees that sip of all in flowery wolds),

We feed upon thy golden sayings all-

Golden, and ever worthiest endless life.

For soon as ever thy planning thought that sprang

From god-like mind begins its loud proclaim

Of nature’s courses, terrors of the brain

Asunder flee, the ramparts of the world

Dispart away, and through the void entire

I see the movements of the universe.

For context, the ktistes (founder, usually of a city, dynasty, or association) was one of the types of figures who enjoyed the status of a Greek hero among their followers. These types of culture heroes often were recipients of a cult and, as public benefactors, were considered worthy of piety by their descendants. Epicurus has become, to the Koinonia or community of philosopher-friends, an embodiment of what Nietzsche in Thus Spake Zarathustra calls their “chief organizing idea”.

Liber Tertivs in general deals with the nature of the soul / mind, and Epicurus is here praised for having a god-like mind. Also, notice that Lucretius here praises the Aurea Dicta (golden precepts) of Epicurus, a subject that we will turn to later in this essay.

After the Aurea Dicta verse, Epicurus is celebrated as a type of polytheistic prophet, a revealer of the tranquil Epicurean gods. Lucretius gives us a poetic epiphany of these gods and their environment, proclaiming that this aspect of Epicurus’ doctrine produces (as intended) god-like trembling awe (terror) and pleasure (divina voluptas) in Lucretius, an awe that is not fear-based but blissful.

Liber Qvartvs

The Fourth Book continues the theme of Epicurus as a Revealer. It says that something new is being inspired, given, new fountains are springing forth and fresh flowers. I wonder if Nietzsche intended to weave Lucretian intertextuality in Thus Spake Zarathustra (portion 25) when he mentioned old fountains bursting forth again. Lucretius again takes up the theme of light and darkness and of enlightened salvation from dreadful religion, saying

since I teach concerning mighty things,

And go right on to loose from round the mind

The tightened coils of dread religion;

Next, since, concerning themes so dark, I frame

Song so pellucid, touching all throughout

Even with the Muses’ charm

The Copley translation (my favorite) of verses 8-9 says: “I turn the bright light of my verse on darkness, painting it all with poetry“. Epicurus and Lucretius both present themselves as Enlighteners and as propagators of the scientific enlightenment.

One further detail I wish to point to here: in the Opening of the First Book of the poem I have previously noticed a Zoroastrian influence (via Empedocles) in Lucretius, where he juxtaposes Venus (peace or concord, pleasure) and Mars (conflict, discord) as two great cosmic ethical forces–see the Love and Strife section of my essay on Empedocles. The verse that refers to “loose from round the mind the tightened coils of dread religion” (religionum animum nodis exsolvere pergo) reminds me of the kushti (cord) that Zoroastrians wear, by which they “bind” themselves to their magical religion, and of the more sinister akedah (binding, and later unbinding) of Isaac by Abraham, who nearly sacrificed his own son to his god.

This, plus the theme in Liber Primvs of liberating humans from religion so that it is trampled underfoot and we are heaven’s equals, helps us to understand Lucretian soteriology in more detail. Lucretius places Epicurus as a symbol or point of reference within history and within the evolution of thought as a similar paradigm shift as other salvific figures: after Epicurus’s Promethean revelations, humans did not need to live in fear of gods anymore, since he healed our souls and prepared us to live pleasantly and correctly. When we compare this with salvific claims made about other figures, we see that Jesus saved people from having to follow Jewish law, and Buddha and Zoroaster both saved people in their culture from animal sacrifices and other practices that they deemed unethical or superstitious. Epicurus, from his own place in history, saved people from fear-based polytheistic practices and refined polytheism, purging it from superstition and providing a prototype for a new, emancipated and enlightened type of human being and a new spirituality. There is a break with the past, and a new and updated type of human being is now possible.

In the latter part of the hymn in Liber Qvartvs, Lucretius reveals himself as a healer. Lucretius is imparting a dose of medicine and shows us how mortals can participate in Epicurus’ soul-healing activity.

I too (since this my doctrine seems

In general somewhat woeful unto those

Who’ve had it not in hand, and since the crowd

Starts back from it in horror) have desired

To expound our doctrine unto thee in song

Soft-speaking and Pierian, and, as ’twere,

To touch it with sweet honey of the Muse-

If by such method haply I might hold

The mind of thee upon these lines of ours,

Till thou dost learn the nature of all things

And understandest their utility.

Liber Qvintvs

This book provides one of the most useful hymns in our investigation of Epicurean salvation. In this book, Epicurus is revealed and proclaimed a god, and his apotheosis and soteriology is justified.

… a god was he,-

Hear me, illustrious Memmius- a god;

Who first and chief found out that plan of life

Which now is called philosophy, and who

By cunning craft, out of such mighty waves,

Out of such mighty darkness, moored life

In havens so serene, in light so clear.

Compare those old discoveries divine

Of others …

Lucretius then compares Epicurus to the other gods and argues that Epicurus did more for us than they, and so we should be more thankful to him.The other gods were credited with slaying mythical monsters whose existence none have ever witnessed, or with providing useful cultural gifts like wine and weaving that men could have done without. Epicurus, on the other hand, is credited with providing necessary goods for salvation. He is credited with giving humans:

- a pure heart (puro pectore, verse 18)

- sweet consolations that soothe the souls of men (verses 20-21)

- purging the heart of lust and fears (verses 45-46), pride, greed, wantonness, debaucheries and sloth (verses 47-48)

- expelling these things from the soul with words, not weapons (dictis, non armis)

As a tangent, we may compare all the evils that Lucretius says Epicurus purged from our hearts with the salvific claims in Lucian’s 10 Assertions on Kyriai Doxai.

Furthermore, the other Gods are demystified and made natural in Book Five, and Lucretius denies that they are truly responsible for the “gifts” they are said to bestow (except in the curious case of Venus, which has been discussed before and deserves a separate essay). The claims of this hymn are part of the larger aim within Liber Qvintvs‘ of demystifying Greek gods and cultural heroes, but Lucretius also elevates mortals like Epicurus to divine status, demonstrating how with the help of philosophy we can be heaven’s equals.

O shall it not be seemly him

To dignify by ranking with the gods?

And all the more since he was wont to give,

Concerning the immortal gods themselves,

Many pronouncements with a tongue divine,

And to unfold by his pronouncements all

The nature of the world.

Liber Sextus

The claims about Epicurus in Book Six, again, mirror Lucian’s claims. Lucretius says that “only truth poured from his lips” (Copley’s translation of veridico), while Lucian says that “he alone knew and imparted truth”. Lucretius says that his god-like revelations have carried his fame to heaven. He then gives a parable which compares the souls of men to punctured jars that are made whole by philosophy so that they may contain the pleasures that nature easily makes available to men.

So he,

The master, then by his truth-speaking words,

Purged the breasts of men, and set the bounds

Of lust and terror, and exhibited

The supreme good whither we all endeavour,

And showed the path whereby we might arrive

Thereunto by a little cross-cut straight

Notice that the salvific power is attributed, specifically, to the words of Epicurus, which is what Philodemus also does in his scroll On Music. This hymn speaks of godlike revelations and depicts the Hegemon as the healer of the soul. This is another theme we often see in other salvific figures, like Buddha and Jesus.

How does polytheism evolve as a result of Epicurus’ apotheosis? Does this represent a move towards pantheism, or panentheism, or towards a type of religious naturalism? My book review of How one can be a god partially answers this. The divine powers and attributes are drawn down to the earthly realm in Lucretius, rather than projected toward heaven, and Lucretius treats Epicurus himself as the prototype of immanent divinity. In the poem, Lucretian Gods are symbols tied to techniques to help us awaken certain spiritual potentials. Since Lucretian Divinity is immanent (remember that Venus, too, is said to “pulsate in the souls of men” in Liber Primvs), we must ex-press them (press them out of our souls), e-voke them (call them out from our souls) rather than in-voke them from the outside.

Personalist vs. Healing Logos Attribution

When we study the salvific theory of the Epicureans, we see two tendencies of attribution: in Lucretius we see a marked tendency to attribute salvific power to the Hegemon, the founder, Epicurus. This is the personalist attribution, although he also mentions “aurea dicta” (golden words) and the power of the healing words of the Hegemon as well.

Philodemus, in his scroll On Music, mentions that music only has healing powers if it contains the words of correct philosophy because it is those words that contain the healing potential, and so his therapeutic approach is logocentric. This is the non-personalist or healing logos approach to salvation, which attributes salvific powers to the words rather than the person uttering them.

In Lucian we see a praise of both Epicurus and his Kyriai Doxai: he endorsed both the personalist and the healing word model of salvation. The two tendencies of attribution are not mutually exclusive, however, the choice of one or the other might reflect the personality or tendencies or values of the person and might be justified with different arguments.

Lucretius focuses on the personalist attribution, which tells me that he feels comfortable with devotional traditions and exercises, that he sees them as serving some kind of important function in the psyche. Arguments in favor of personifying deity and choosing personal conceptions of spirituality rather than abstract ones exist in traditions that focus on devotion, like the Gaudiya Vaishnava lineage of Hinduism. In general, the argument I’ve heard from that lineage (which expound on passages from the scriptures like the Bhagavad Gita and Bhagavatam) is that humans find it easier to relate to a Person than to an abstraction. The personalist attribution is based on the theory that the psyche has a social set of faculties and functions, that it seeks to relate to an other self, and that it learns to relate to others by playing or rehearsing loving relationships. Play behavior also serves educational purposes in other species: we see cubs and kittens playing to learn social hierarchy, stalking behavior, and other important skills that will be later useful. Hindus refer to the playful pastimes of Krishna as “lila” (divine play).

Perhaps the issue of personal versus impersonal attribution of salvific power can be understood in terms of different types of Epicureans with different constitutions, some more social than others or more willing to take up external points of reference, or as attempts to develop different faculties of the soul.

Conclusion

In this essay I’ve tried to compile and evaluate some of the soteriological claims made and parables used by Lucretius in De rerum natura, particularly in the five hymns that he dedicates to the Hegemon, where Lucretius makes attributions to Epicurus as a Revealer of cosmic truths, a Healer of souls, a Promethean Savior of humanity from religious oppression and disinformation, a Liberator, and a deified mortal. We also see a pattern of presenting Epicurus as a scientific Enlightener who sheds his light upon darkness, and we see that Lucretius participates in these salvific activities by virtue of his poem and his efforts to propagate philosophy.

I’ve had the pleasure of reading Copley’s translation of De Rerum natura (

I’ve had the pleasure of reading Copley’s translation of De Rerum natura (