In Praise of Lucian of Samosata, the 2nd-Century author

Alexander the Oracle Monger is an exposé of a religious fraud. The Fowler translation divides it apparently according to Greek lines or paragraphs. For ease of citation, we have preserved that convention. Because the text is long, of great historical value, and useful for teaching philosophy and critical thinking, the Friends of Epicurus feel that it is useful to keep and use these portions in order to more easily find a specific citation. We recommend the use of citations that look like “AOM 25”, etc. and we recommend that these divisions be called “portions”.

[1] You, my dear Celsus, possibly suppose yourself to be laying upon me quite a trifling task: Write me down in a book and send me the life and adventures, the tricks and frauds, of the impostor Alexander of Abonutichus. In fact, however, it would take as long to do this in full detail as to reduce to writing the achievements of Alexander of Macedon; the one is among villains what the other is among heroes. Nevertheless, if you will promise to read with indulgence, and fill up the gaps in my tale from your imagination, I will essay the task. I may not cleanse that Augean stable completely, but I will do my best, and fetch you out a few loads as samples of the unspeakable filth that three thousand oxen could produce in many years.

[2] I confess to being a little ashamed both on your account and my own. There are you asking that the memory of an arch-scoundrel should be perpetuated in writing; here am I going seriously into an investigation of this sort—the doings of a person whose deserts entitled him not to be read about by the cultivated, but to be torn to pieces in the amphitheater by apes or foxes, with a vast audience looking on. Well, well, if any one does cast reflections of that sort upon us, we shall at least have a precedent to plead. Arrian himself, disciple of Epictetus, distinguished Roman, and product of lifelong culture as he was, had just our experience, and shall make our defense. He condescended, that is, to put on record the life of the robber Tilliborus. The robber we propose to immortalize was of a far more pestilent kind, following his profession not in the forests and mountains, but in cities; he was not content to overrun a Mysia or an Ida; his booty came not from a few scantily populated districts of Asia; one may say that the scene of his depredations was the whole Roman Empire.

[3] I will begin with a picture of the man himself, as lifelike (though I am not great at description) as I can make it with nothing better than words. In person—not to forget that part of him—he was a fine handsome man with a real touch of divinity about him, white-skinned, moderately bearded; he wore besides his own hair artificial additions which matched it so cunningly that they were not generally detected. His eyes were piercing, and suggested inspiration, his voice at once sweet and sonorous. In fact there was no fault to be found with him in these respects.

[4] So much for externals. As for his mind and spirit—well, if all the kind Gods who avert disaster will grant a prayer, it shall be that they bring me not within reach of such a one as he; sooner will I face my bitterest enemies, my country’s foes. In understanding, resource, acuteness, he was far above other men; curiosity, receptiveness, memory, scientific ability—all these were his in overflowing measure. But he used them for the worst purposes. Endowed with all these instruments of good, he very soon reached a proud pre-eminence among all who have been famous for evil; the Cercopes, Eurybatus, Phrynondas, Aristodemus, Sostratus—all thrown into the shade. In a letter to his father-in-law Rutilianus, which puts his own pretensions in a truly modest light, he compares himself to Pythagoras.

Well, I should not like to offend the wise, the divine Pythagoras; but if he had been Alexander’s contemporary, I am quite sure he would have been a mere child to him. Now by all that is admirable, do not take that for an insult to Pythagoras, nor suppose I would draw a parallel between their achievements. What I mean is: if any one would make a collection of all the vilest and most damaging slanders ever vented against Pythagoras—things whose truth I would not accept for a moment—, the sum of them would not come within measurable distance of Alexander’s cleverness. You are to set your imagination to work and conceive a temperament curiously compounded of falsehood, trickery, perjury, cunning; it is versatile, audacious, adventurous, yet dogged in execution; it is plausible enough to inspire confidence; it can assume the mask of virtue, and seem to eschew what it most desires. I suppose no one ever left him after a first interview without the impression that this was the best and kindest of men, aye, and the simplest and most unsophisticated. Add to all this a certain greatness in his objects; he never made a small plan; his ideas were always large.

[5] While in the bloom of his youthful beauty, which we may assume to have been great both from its later remains and from the report of those who saw it, he traded quite shamelessly upon it. Among his other patrons was one of the charlatans who deal in magic and mystic incantations; they will smooth your course of love, confound your enemies, find you treasure, or secure you an inheritance. This person was struck with the lad’s natural qualifications for apprenticeship to his trade, and finding him as much attracted by rascality as attractive in appearance, gave him a regular training as accomplice, satellite, and attendant. His own ostensible profession was medicine, and his knowledge included, like that of Thoon the Egyptian’s wife, Many a virtuous herb, and many a bane; to all which inheritance our friend succeeded. This teacher and lover of his was a native of Tyana, an associate of the great Apollonius, and acquainted with all his heroics. And now you know the atmosphere in which Alexander lived.

[6] By the time his beard had come, the Tyanean was dead, and he found himself in straits; for the personal attractions which might once have been a resource were diminished. He now formed great designs, which he imparted to a Byzantine chronicler of the strolling competitive order, a man of still worse character than himself, called, I believe, Cocconas. The pair went about living on occult pretensions, shearing ‘fat-heads,’ as they describe ordinary people in the native Magian lingo. Among these they got hold of a rich Macedonian woman; her youth was past, but not her desire for admiration; they got sufficient supplies out of her, and accompanied her from Bithynia to Macedonia. She came from Pella, which had been a flourishing place under the Macedonian kingdom, but has now a poor and much reduced population.

[7] There is here a breed of large serpents, so tame and gentle that women make pets of them, children take them to bed, they will let you tread on them, have no objection to being squeezed, and will draw milk from the breast like infants. To these facts is probably to be referred the common story about Olympias when she was with child of Alexander; it was doubtless one of these that was her bed-fellow. Well, the two saw these creatures, and bought the finest they could get for a few pence.

[8] And from this point, as Thucydides might say, the war takes its beginning. These ambitious scoundrels were quite devoid of scruples, and they had now joined forces; it could not escape their penetration that human life is under the absolute dominion of two mighty principles, fear and hope, and that any one who can make these serve his ends may be sure of a rapid fortune. They realized that, whether a man is most swayed by the one or by the other, what he must most depend upon and desire is a knowledge of futurity. So were to be explained the ancient wealth and fame of Delphi, Delos, Clarus, Branchidae; it was at the bidding of the two tyrants aforesaid that men thronged the temples, longed for foreknowledge, and to attain it sacrificed their hecatombs or dedicated their golden ingots. All this they turned over and debated, and it issued in the resolve to establish an oracle. If it were successful, they looked for immediate wealth and prosperity; the result surpassed their most sanguine expectations.

[9] The next things to be settled were, first the theater of operations, and secondly the plan of campaign. Cocconas favoured Chalcedon, as a mercantile center convenient both for Thrace and Bithynia, and accessible enough for the province of Asia, Galatia, and tribes still further east. Alexander, on the other hand, preferred his native place, urging very truly that an enterprise like theirs required congenial soil to give it a start, in the shape of ‘fat-heads’ and simpletons. That was a fair description, he said, of the Paphlagonians beyond Abonutichus; they were mostly superstitious and well-to-do; one had only to go there with some one to play the flute, the tambourine, or the cymbals, set the proverbial mantic sieve a-spinning, and there they would all be gaping as if he were a God from heaven.

[10] This difference of opinion did not last long, and Alexander prevailed. Discovering, however, that a use might after all be made of Chalcedon, they went there first, and in the temple of Apollo, the oldest in the place, they buried some brazen tablets, on which was the statement that very shortly Asclepius, with his father Apollo, would pay a visit to Pontus, and take up his abode at Abonutichus. The discovery of the tablets took place as arranged, and the news flew through Bithynia and Pontus, first of all, naturally, to Abonutichus. The people of that place at once resolved to raise a temple, and lost no time in digging the foundations. Cocconas was now left at Chalcedon, engaged in composing certain ambiguous crabbed oracles. He shortly afterwards died, I believe, of a viper’s bite.

[11] Alexander meanwhile went on in advance; he had now grown his hair and wore it in long curls; his doublet was white and purple striped, his cloak pure white; he carried a scimitar in imitation of Perseus, from whom he now claimed descent through his mother. The wretched Paphlagonians, who knew perfectly well that his parentage was obscure and mean on both sides, nevertheless gave credence to the oracle, which ran: Lo, sprung from Perseus, and to Phoebus dear, High Alexander, Podalirius’ son!

Podalirius, it seems, was of so highly amorous a complexion that the distance between Tricca and Paphlagonia was no bar to his union with Alexander’s mother. A Sibylline prophecy had also been found:

Hard by Sinope on the Euxine shore Th’ Italic age a fortress prophet sees. To the first monad let thrice ten be added, Five monads yet, and then a triple score: Such the quaternion of th’ alexic name.

[12] This heroic entry into his long-left home placed Alexander conspicuously before the public; he affected madness, and frequently foamed at the mouth— a manifestation easily produced by chewing the herb soap-wort, used by dyers; but it brought him reverence and awe. The two had long ago manufactured and fitted up a serpent’s head of linen; they had given it a more or less human expression, and painted it very like the real article; by a contrivance of horsehair, the mouth could be opened and shut, and a forked black serpent tongue protruded, working on the same system. The serpent from Pella was also kept ready in the house, to be produced at the right moment and take its part in the drama—the leading part, indeed.

[13] In the fullness of time, his plan took shape. He went one night to the temple foundations, still in process of digging, and with standing water in them which had collected from the rainfall or otherwise. Here he deposited a goose egg, into which, after blowing it, he had inserted some new-born reptile. He made a resting-place deep down in the mud for this, and departed. Early next morning he rushed into the market-place, naked except for a gold-spangled loin-cloth; with nothing but this and his scimetar, and shaking his long loose hair, like the fanatics who collect money in the name of Cybele, he climbed on to a lofty altar and delivered a harangue, felicitating the city upon the advent of the God now to bless them with his presence. In a few minutes nearly the whole population was on the spot, women, old men, and children included; all was awe, prayer, and adoration. He uttered some unintelligible sounds, which might have been Hebrew or Phoenician, but completed his victory over his audience, who could make nothing of what he said, beyond the constant repetition of the names Apollo and Asclepius.

[14] He then set off at a run for the future temple. Arrived at the excavation and the already completed sacred fount, he got down into the water, chanted in a loud voice hymns to Asclepius and Apollo, and invited the God to come, a welcome guest, to the city. He next demanded a bowl, and when this was handed to him, had no difficulty in putting it down at the right place and scooping up, besides water and mud, the egg in which the God had been enclosed; the edges of the aperture had been joined with wax and white lead. He took the egg in his hand and announced that here he held Asclepius. The people, who had been sufficiently astonished by the discovery of the egg in the water, were now all eyes for what was to come. He broke it, and received in his hollowed palm the hardly developed reptile; the crowd could see it stirring and winding about his fingers; they raised a shout, hailed the God, blessed the city, and every mouth was full of prayers—for treasure and wealth and health and all the other good things that he might give. Our hero now departed homewards, still running, with the new-born Asclepius in his hands—the twice-born, too, whereas ordinary men can be born but once, and born moreover not of Coronis, nor even of her namesake the crow, but of a goose! After him streamed the whole people, in all the madness of fanatic hopes.

[15] He now kept the house for some days, in hopes that the Paphlagonians would soon be drawn in crowds by the news. He was not disappointed; the city was filled to overflowing with persons who had neither brains nor individuality, who bore no resemblance to men that live by bread, and had only their outward shape to distinguish them from sheep. In a small room he took his seat, very imposingly attired, upon a couch. He took into his bosom our Asclepius of Pella (a very fine and large one, as I observed), wound its body round his neck, and let its tail hang down. There was enough of this not only to fill his lap, but to trail on the ground also; the patient creature’s head he kept hidden in his armpit, showing the linen head on one side of his beard exactly as if it belonged to the visible body.

[16] Picture to yourself a little chamber into which no very brilliant light was admitted, with a crowd of people from all quarters, excited, carefully worked up, all aflutter with expectation. As they came in, they might naturally find a miracle in the development of that little crawling thing of a few days ago into this great, tame, human-looking serpent. Then they had to get on at once towards the exit, being pressed forward by the new arrivals before they could have a good look. An exit had been specially made just opposite the entrance, for all the world like the Macedonian device at Babylon when Alexander was ill. He was in extremis, you remember, and the crowd round the palace were eager to take their last look and give their last greeting. Our scoundrel’s exhibition, though, is said to have been given not once, but many times, especially for the benefit of any wealthy new-comers.

[17] And at this point, my dear Celsus, we may, if we will be candid, make some allowance for these Paphlagonians and Pontics. The poor uneducated ‘fat-heads’ might well be taken in when they handled the serpent—a privilege conceded to all who choose—and saw in that dim light its head with the mouth that opened and shut. It was an occasion for a Democritus, nay, for an Epicurus or a Metrodorus, perhaps, a man whose intelligence was steeled against such assaults by skepticism and insight, one who, if he could not detect the precise imposture, would at any rate have been perfectly certain that, though this escaped him, the whole thing was a lie and an impossibility.

[18] By degrees Bithynia, Galatia, Thrace, came flocking in, every one who had been present doubtless reporting that he had beheld the birth of the God, and had touched him after his marvelous development in size and in expression. Next came pictures and models, bronze or silver images, and the God acquired a name. By divine command, metrically expressed, he was to be known as Glycon. For Alexander had delivered the line: Glycon my name, man’s light, son’s son to Zeus.

[19] And now at last the object to which all this had led up, the giving of oracular answers to all applicants, could be attained. The cue was taken from Amphilochus in Cilicia. After the death and disappearance at Thebes of his father Amphiaraus, Amphilochus, driven from his home, made his way to Cilicia, and there did not at all badly by prophesying to the Cilicians at the rate of threepence an oracle. After this precedent, Alexander proclaimed that on a stated day the God would give answers to all comers. Each person was to write down his wish and the object of his curiosity, fasten the packet with thread, and seal it with wax, clay, or other such substance. He would receive these, and enter the holy place (by this time the temple was complete, and the scene all ready), whither the givers should be summoned in order by a herald and an acolyte. He would learn the God’s mind upon each, and return the packets with their seals intact and the answers attached, the God being ready to give a definite answer to any question that might be put.

[20] The trick here was one which would be seen through easily enough by a person of your intelligence (or, if I may say so without violating modesty, of my own), but which to the ordinary imbecile would have the persuasiveness of what is marvelous and incredible. He contrived various methods of undoing the seals, read the questions, answered them as seemed good, and then folded, sealed, and returned them, to the great astonishment of the recipients. And then it was, ‘How could he possibly know what I gave him carefully secured under a seal that defies imitation, unless he were a true God, with a God’s omniscience?’

[21] Perhaps you will ask what these contrivances were; well, then—the information may be useful another time. One of them was this. He would heat a needle, melt with it the under part of the wax, lift the seal off, and after reading warm the wax once more with the needle—both that below the thread and that which formed the actual seal—and re-unite the two without difficulty. Another method employed the substance called collyrium; this is a preparation of Bruttian pitch, bitumen, pounded glass, wax, and mastich. He kneaded the whole into collyrium, heated it, placed it on the seal, previously moistened with his tongue, and so took a mould. This soon hardened; he simply opened, read, replaced the wax, and reproduced an excellent imitation of the original seal as from an engraved stone. One more I will give you. Adding some gypsum to the glue used in book-binding he produced a sort of wax, which was applied still wet to the seal, and on being taken off solidified at once and provided a matrix harder than horn, or even iron. There are plenty of other devices for the purpose, to rehearse which would seem like airing one’s knowledge. Moreover, in your excellent pamphlets against the magicians (most useful and instructive reading they are) you have yourself collected enough of them—many more than those I have mentioned.

[22] So oracles and divine utterances were the order of the day, and much shrewdness he displayed, eking out mechanical ingenuity with obscurity, his answers to some being crabbed and ambiguous, and to others absolutely unintelligible. He did however distribute warning and encouragement according to his lights, and recommend treatments and diets; for he had, as I originally stated, a wide and serviceable acquaintance with drugs. He was particularly given to prescribing ‘cytmides,’ which were a salve prepared from goat’s fat, the name being of his own invention. For the realization of ambitions, advancement, or successions, he took care never to assign early dates; the formula was, ‘All this shall come to pass when it is my will, and when my prophet Alexander shall make prayer and entreaty on your behalf.’

[23] There was a fixed charge of a shilling the oracle. And, my friend, do not suppose that this would not come to much; he made something like L3,000 per annum; people were insatiable—would take from ten to fifteen oracles at a time. What he got he did not keep to himself, nor put it by for the future; what with accomplices, attendants, inquiry agents, oracle writers and keepers, amanuenses, seal-forgers, and interpreters, he had now a host of claimants to satisfy.

[24] He had begun sending emissaries abroad to make the shrine known in foreign lands; his prophecies, discovery of runaways, conviction of thieves and robbers, revelations of hidden treasure, cures of the sick, restoration of the dead to life—all these were to be advertised. This brought them running and crowding from all points of the compass; victims bled, gifts were presented, and the prophet and disciple came off better than the God; for had not the oracle spoken?—

Give what ye give to my attendant priest; My care is not for gifts, but for my priest.

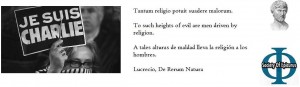

[25] A time came when a number of sensible people began to shake off their intoxication and combine against him, chief among them the numerous Epicureans; in the cities, the imposture with all its theatrical accessories began to be seen through. It was now that he resorted to a measure of intimidation; he proclaimed that Pontus was overrun with atheists and Christians, who presumed to spread the most scandalous reports concerning him. He exhorted Pontus, as it valued the God’s favor, to stone these men. Touching Epicurus, he gave the following response. An inquirer had asked how Epicurus fared in Hades, and was told: Of slime is his bed, And his fetters of lead.

The prosperity of the oracle is perhaps not so wonderful, when one learns what sensible, intelligent questions were in fashion with its votaries. Well, it was war to the knife between him and Epicurus, and no wonder. What fitter enemy for a charlatan who patronized miracles and hated truth, than the thinker who had grasped the nature of things and was in solitary possession of that truth? As for the Platonists, Stoics, Pythagoreans, they were his good friends; he had no quarrel with them. But the unmitigated Epicurus, as he used to call him, could not but be hateful to him, treating all such pretensions as absurd and puerile. Alexander consequently loathed Amastris beyond all the cities of Pontus, knowing what a number of Lepidus’s friends and others like-minded it contained. He would not give oracles to Amastrians; when he once did, to a senator’s brother, he made himself ridiculous, neither hitting upon a presentable oracle for himself, nor finding a deputy equal to the occasion. The man had complained of colic, and what he meant to prescribe was pig’s foot dressed with mallow. The shape it took was: In basin hallowed, Be pigments mallowed.

[26] I have mentioned that the serpent was often exhibited by request; he was not completely visible, but the tail and body were exposed, while the head was concealed under the prophet’s dress. By way of impressing the people still more, he announced that he would induce the God to speak, and give his responses without an intermediary. His simple device to this end was a tube of cranes’ windpipes, which he passed, with due regard to its matching, through the artificial head, and, having an assistant speaking into the end outside, whose voice issued through the linen Asclepius, thus answered questions. These oracles were called autophones, and were not vouchsafed casually to any one, but reserved for officials, the rich, and the lavish.

[27] It was an autophone which was given to Severian regarding the invasion of Armenia. He encouraged him with these lines:

Armenia, Parthia, cowed by thy fierce spear, To Rome, and Tiber’s shining waves, thou com’st, Thy brow with leaves and radiant gold encircled.

Then when the foolish Gaul took his advice and invaded, to the total destruction of himself and his army by Othryades, the adviser expunged that oracle from his archives and substituted the following:

Vex not th’ Armenian land; it shall not thrive; One in soft raiment clad shall from his bow Launch death, and cut thee off from life and light.

[28] For it was one of his happy thoughts to issue prophecies after the event as antidotes to those premature utterances which had not gone right. Frequently he promised recovery to a sick man before his death, and after it was at no loss for second thoughts:

No longer seek to arrest thy fell disease; Thy fate is manifest, inevitable.

[29] Knowing the fame of Clarus, Didymus, and Mallus for sooth-saying much like his own, he struck up an alliance with them, sending on many of his clients to those places. So Hie thee to Clarus now, and hear my sire. And again, Draw near to Branchidae and counsel take. Or Seek Mallus; be Amphilochus thy counsellor.

[30] So things went within the borders of Ionia, Cilicia, Paphlagonia, and Galatia. When the fame of the oracle traveled to Italy and entered Rome, the only question was, who should be first; those who did not come in person sent messages, the powerful and respected being the keenest of all. First and foremost among these was Rutilianus. He was in most respects an excellent person, and had filled many high offices in Rome; but he suffered from religious mania, holding the most extraordinary beliefs on that matter. Show him a bit of stone smeared with unguents or crowned with flowers, and he would incontinently fall down and worship, and linger about it praying and asking for blessings. The reports about our oracle nearly induced him to throw up the appointment he then held, and fly to Abonutichus; he actually did send messenger upon messenger. His envoys were ignorant servants, easily taken in. They came back having really seen certain things, relating others which they probably thought they had seen and heard, and yet others which they deliberately invented to curry favor with their master. So they inflamed the poor old man and drove him into confirmed madness.

[31] He had a wide circle of influential friends, to whom he communicated the news brought by his successive messengers, not without additional touches of his own. All Rome was full of his tales; there was quite a commotion, the gentlemen of the Court being much fluttered, and at once taking measures to learn something of their own fate. The prophet gave all who came a hearty welcome, gained their goodwill by hospitality and costly gifts, and sent them off ready not merely to report his answers, but to sing the praises of the God and invent miraculous tales of the shrine and its guardian.

[32] This triple rogue now hit upon an idea which would have been too clever for the ordinary robber. Opening and reading the packets which reached him, whenever he came upon an equivocal, compromising question, he omitted to return the packet. The sender was to be under his thumb, bound to his service by the terrifying recollection of the question he had written down. You know the sort of things that wealthy and powerful personages would be likely to ask. This blackmail brought him in a good income.

[33] I should like to quote you one or two of the answers given to Rutilianus. He had a son by a former wife, just old enough for advanced teaching. The father asked who should be his tutor, and was told, Pythagoras, and the mighty battle-bard.

When the child died a few days after, the prophet was abashed, and quite unable to account for this summary confutation. However, dear good Rutilianus very soon restored the oracle’s credit by discovering that this was the very thing the God had foreshown – he had not directed him to choose a living teacher; Pythagoras and Homer were long dead, and doubtless the boy was now enjoying their instructions in Hades. Small blame to Alexander if he had a taste for dealings with such specimens of humanity as this.

[34] Another of Rutilianus’s questions was, Whose soul he had succeeded to, and the answer:

First thou wast Peleus’ son, and next Menander; Then thine own self; next, a sunbeam shalt be; And nine score annual rounds thy life shall measure.

At seventy, he died of melancholy, not waiting for the God to pay in full.

[35] That was an autophone too. Another time Rutilianus consulted the oracle on the choice of a wife. The answer was express: Wed Alexander’s daughter and Selene’s.

He had long ago spread the report that the daughter he had had was by Selene: she had once seen him asleep, and fallen in love, as is her way with handsome sleepers. The sensible Rutilianus lost no time, but sent for the maiden at once, celebrated the nuptials, a sexagenarian bridegroom, and lived with her, propitiating his divine mother-in-law with whole hecatombs, and reckoning himself now one of the heavenly company.

[36] His finger once in the Italian pie, Alexander devoted himself to getting further. Sacred envoys were sent all over the Roman Empire, warning the various cities to be on their guard against pestilence and conflagrations, with the prophet’s offers of security against them. One oracle in particular, an autophone again, he distributed broadcast at a time of pestilence. It was a single line: Phoebus long-tressed the plague-cloud shall dispel.

This was everywhere to be seen written up on doors as a prophylactic. Its effect was generally disappointing; for it somehow happened that the protected houses were just the ones to be desolated. Not that I would suggest for a moment that the line was their destruction; but, accidentally no doubt, it did so fall out. Possibly common people put too much confidence in the verse, and lived carelessly without troubling to help the oracle against its foe. Were there not the words fighting their battle, and long-tressed Phoebus discharging his arrows at the pestilence?

[37] In Rome itself he established an intelligence bureau well manned with his accomplices. They sent him people’s characters, forecasts of their questions, and hints of their ambitions, so that he had his answers ready before the messengers reached him.

[38] It was with his eye on this Italian propaganda, too, that he took a further step. This was the institution of mysteries, with hierophants and torch-bearers complete. The ceremonies occupied three successive days. On the first, proclamation was made on the Athenian model to this effect:

‘If there be any atheist or Christian or Epicurean here spying upon our rites, let him depart in haste; and let all such as have faith in the God be initiated and all blessing attend them.’ He led the litany with, ‘Christians, avaunt!’ and the crowd responded, ‘Epicureans, avaunt!’

Then was presented the child-bed of Leto and birth of Apollo, the bridal of Coronis, Asclepius born.

The second day, the epiphany and nativity of the God Glycon.

[39] On the third came the wedding of Podalirius and Alexander’s mother; this was called Torch-day, and torches were used. The finale was the loves of Selene and Alexander, and the birth of Rutilianus’s wife. The torch- bearer and hierophant was Endymion-Alexander. He was discovered lying asleep; to him from heaven, represented by the ceiling, enter as Selene one Rutilia, a great beauty, and wife of one of the Imperial procurators. She and Alexander were lovers off the stage too, and the wretched husband had to look on at their public kissing and embracing. If there had not been a good supply of torches, things might possibly have gone even further. Shortly after, he reappeared amidst a profound hush, attired as hierophant; in a loud voice he called, ‘Hail, Glycon!’, whereto the Eumolpidae and Ceryces of Paphlagonia, with their clod-hopping shoes and their garlic breath, made sonorous response, ‘Hail, Alexander!’

[40] The torch ceremony with its ritual skippings often enabled him to bestow a glimpse of his thigh, which was thus discovered to be of gold; it was presumably enveloped in cloth of gold, which glittered in the lamp-light. This gave rise to a debate between two wiseacres, whether the golden thigh meant that he had inherited Pythagoras’s soul, or merely that their two souls were alike; the question was referred to Alexander himself, and King Glycon relieved their perplexity with an oracle:

Waxes and wanes Pythagoras’ soul: the seer’s Is from the mind of Zeus an emanation. His Father sent him, virtuous men to aid, And with his bolt one day shall call him home.

[41] Although he cautioned all to abstain from intercourse with boys on the grounds that it was impious, for his own part this pattern of propriety made a clever arrangement. He commanded the cities of Pontus and Paphlagonia to send choir-boys for three years’ service, to sing hyms to the god in his household; they were required examine, select, and send the noblest, youngest, and most handsome. These he kept under ward and treated like bought slaves, sleeping with them and affronting them in every way. He made it a rule, too, not to greet anyone over eighteen years with his lips, or to embrace and kiss him; he kissed only the young, extending his hand to the others to be kissed by them. They were called “those within the kiss.”

[42] He duped the simpletons in this way from first to last, ruining women right and left as well as living with favourites. Indeed, it was a great thing that eveyone coveted if he simply cast his eyes upon a man’s wife; if, however, he deemed her worthy of a kiss, each husband thought that good fortune would flood his house. Many women even boasted that they had children by Alexander, and their husbands bore witness that they spoke the truth!

[43] I will now give you a conversation between Glycon and one Sacerdos of Tius; the intelligence of the latter you may gauge from his questions. I read it inscribed in golden letters in Sacerdos’s house at Tius.

‘Tell me, lord Glycon,’ said he, ‘who you are.’ ‘The new Asclepius.’ ‘Another, different from the former one? Is that the meaning?’ ‘That it is not lawful for you to learn.’ ‘And how many years will you sojourn and prophesy among us?’ ‘A thousand and three.’ ‘And after that, whither will you go?’ ‘To Bactria; for the barbarians too must be blessed with my presence.’ ‘The other oracles, at Didymus and Clarus and Delphi, have they still the spirit of your grandsire Apollo, or are the answers that now come from them forgeries?’ ‘That, too, desire not to know; it is not lawful.’ ‘What shall I be after this life?’ ‘A camel; then a horse; then a wise man, no less a prophet than Alexander.’

Such was the conversation. There was added to it an oracle in verse, inspired by the fact that Sacerdos was an associate of Lepidus: Shun Lepidus; an evil fate awaits him.

As I have said, Alexander was much afraid of Epicurus, and the solvent action of his logic on imposture.

[44] On one occasion, indeed, an Epicurean got himself into great trouble by daring to expose him before a great gathering. He came up and addressed him in a loud voice.

‘Alexander, it was you who induced So-and-so the Paphlagonian to bring his slaves before the governor of Galatia, charged with the murder of his son who was being educated in Alexandria. Well, the young man is alive, and has come back, to find that the slaves had been cast to the beasts by your machinations.’

What had happened was this. The lad had sailed up the Nile, gone on to a Red Sea port, found a vessel starting for India, and been persuaded to make the voyage. He being long overdue, the unfortunate slaves supposed that he had either perished in the Nile or fallen a victim to some of the pirates who infested it at that time; so they came home to report his disappearance. Then followed the oracle, the sentence, and finally the young man’s return with the story of his absence.

[45] All this the Epicurean recounted. Alexander was much annoyed by the exposure, and could not stomach so well deserved an affront. He directed the company to stone the man, on pain of being involved in his impiety and called Epicureans. However, when they set to work, a distinguished Pontic called Demostratus, who was staying there, rescued him by interposing his own body. The man had the narrowest possible escape from being stoned to death—as he richly deserved to be; what business had he to be the only sane man in a crowd of madmen, and needlessly make himself the butt of Paphlagonian infatuation?

[46] This was a special case; but it was the practice for the names of applicants to be read out the day before answers were given. The herald asked whether each was to receive his oracle; and sometimes the reply came from within, To perdition! One so repulsed could get shelter, fire or water, from no man; he must be driven from land to land as a blasphemer, an atheist, and—lowest depth of all—an Epicurean.

[47] In this connection Alexander once made himself supremely ridiculous. Coming across Epicurus’s Accepted Maxims, the most admirable of his books, as you know, with its terse presentment of his wise conclusions, he brought it into the middle of the market-place, there burned it on a fig-wood fire for the sins of its author, and cast its ashes into the sea. He issued an oracle on the occasion: The dotard’s maxims to the flames be given.

The fellow had no conception of the blessings conferred by that book upon its readers, of the peace, tranquillity, and independence of mind it produces, of the protection it gives against terrors, phantoms, and marvels, vain hopes and inordinate desires, of the judgment and candor that it fosters, or of its true purging of the spirit, not with torches and squills and such rubbish, but with right reason, truth, and frankness.

[48] Perhaps the greatest example of our rogue’s audacity is what I now come to. Having easy access to Palace and Court by Rutilianus’s influence, he sent an oracle just at the crisis of the German war, when M. Aurelius was on the point of engaging the Marcomanni and Quadi. The oracle required that two lions should be flung alive into the Danube, with quantities of sacred herbs and magnificent sacrifices. I had better give the words:

To rolling Ister, swoln with Heaven’s rain, Of Cybelean thralls, those mountain beasts, Fling ye a pair; therewith all flowers and herbs Of savour sweet that Indian air doth breed. Hence victory, and fame, and lovely peace.

These directions were precisely followed: the lions swam across to the enemy’s bank, where they were clubbed to death by the barbarians, who took them for dogs or a new kind of wolves; and our forces immediately after met with a severe defeat, losing some twenty thousand men in one engagement. This was followed by the Aquileian incident, in the course of which that city was nearly lost. In view of these results, Alexander warmed up that stale Delphian defense of the Croesus oracle: the God had foretold a victory, forsooth, but had not stated whether Romans or barbarians should have it.

[49] The constant increase in the number of visitors, the inadequacy of accommodation in the city, and the difficulty of finding provisions for consultants, led to his introducing what he called night oracles. He received the packets, slept upon them, in his own phrase, and gave answers which the God was supposed to send him in dreams. These were generally not lucid, but ambiguous and confused, especially when he came to packets sealed with exceptional care. He did not risk tampering with these, but wrote down any words that came into his head, the results obtained corresponding well enough to his conception of the oracular. There were regular interpreters in attendance, who made considerable sums out of the recipients by expounding and unriddling these oracles. This office contributed to his revenue, the interpreters paying him L250 each.

[50] Sometimes he stirred the wonder of the silly by answers to persons who had neither brought nor sent questions, and in fact did not exist. Here is a specimen:

Who is’t, thou askst, that with Calligenia All secretly defiles thy nuptial bed? The slave Protogenes, whom most thou trustest. Him thou enjoyedst: he thy wife enjoys— The fit return for that thine outrage done. And know that baleful drugs for thee are brewed, Lest thou or see or hear their evil deeds. Close by the wall, at thy bed’s head, make search. Thy maid Calypso to their plot is privy.

The names and circumstantial details might stagger a Democritus, till a moment’s thought showed him the despicable trick.

[51] He often gave answers in Syriac or Celtic to barbarians who questioned him in their own tongue, though he had difficulty in finding compatriots of theirs in the city. In these cases there was a long interval between application and response, during which the packet might be securely opened at leisure, and somebody found capable of translating the question. The following is an answer given to a Scythian:

Morphi ebargulis for night Chnenchicrank shall leave the light.

[52] Another oracle to some one who neither came nor existed was in prose. ‘Return the way thou earnest,‘ it ran; ‘for he that sent thee hath this day been slain by his neighbour Diocles, with aid of the robbers Magnus, Celer, and Bubalus, who are taken and in chains.’

[53] I must give you one or two of the answers that fell to my share. I asked whether Alexander was bald, and having sealed it publicly with great care, got a night oracle in reply: Sabardalachu malach Attis was not he.

Another time I did up the same question—What was Homer’s birthplace?—in two packets given in under different names. My servant misled him by saying, when asked what he came for, a cure for lung trouble; so the answer to one packet was: Cytmide and foam of steed the liniment give.

As for the other packet, he got the information that the sender was inquiring whether the land or the sea route to Italy was preferable. So he answered, without much reference to Homer: Fare not by sea; land-travel meets thy need.

[54] I laid a good many traps of this kind for him; here is another. I asked only one question, but wrote outside the packet in the usual form, So- and-so’s eight queries, giving a fictitious name and sending the eight shillings. Satisfied with the payment of the money and the inscription on the packet, he gave me eight answers to my one question. This was, When will Alexander’s imposture be detected? The answers concerned nothing in heaven or earth, but were all silly and meaningless together. He afterwards found out about this, and also that I had tried to dissuade Rutilianus both from the marriage and from putting any confidence in the oracle; so he naturally conceived a violent dislike for me. When Rutilianus once put a question to him about me, the answer was: Night-haunts and foul debauch are all his joy.

[55] It is true his dislike was quite justified. On a certain occasion I was passing through Abonutichus, with a spearman and a pikeman whom my friend the governor of Cappadocia had lent me as an escort on my way to the sea. Ascertaining that I was the Lucian he knew of, he sent me a very polite and hospitable invitation. I found him with a numerous company; by good luck I had brought my escort. He gave me his hand to kiss according to his usual custom. I took hold of it as if to kiss, but instead bestowed on it a sound bite that must have come near disabling it. The company, who were already offended at my calling him Alexander instead of Prophet, were inclined to throttle and beat me for sacrilege. But he endured the pain like a man, checked their violence, and assured them that he would easily tame me, and illustrate Glycon’s greatness in converting his bitterest foes to friends. He then dismissed them all, and argued the matter with me: he was perfectly aware of my advice to Rutilianus; why had I treated him so, when I might have been preferred by him to great influence in that quarter? By this time I had realized my dangerous position, and was only too glad to welcome these advances; I presently went my way in all friendship with him. The rapid change wrought in me greatly impressed the observers.

[56] When I intended to sail, he sent me many parting gifts, and offered to find us (Xenophon and me, that is; I had sent my father and family on to Amastris) a ship and crew—which offer I accepted in all confidence. When the passage was half over, I observed the master in tears arguing with his men, which made me very uneasy. It turned out that Alexander’s orders were to seize and fling us overboard; in that case his war with me would have been lightly won. But the crew were prevailed upon by the master’s tears to do us no harm.

‘I am sixty years old, as you can see,’ he said to me; ‘I have lived an honest blameless life so far, and I should not like at my time of life, with a wife and children too, to stain my hands with blood.’ And with that preface he informed us what we were there for, and what Alexander had told him to do.

[57] He landed us at Aegiali, of Homeric fame, and thence sailed home. Some Bosphoran envoys happened to be passing, on their way to Bithynia with the annual tribute from their king Eupator. They listened kindly to my account of our dangerous situation, I was taken on board, and reached Amastris safely after my narrow escape. From that time it was war between Alexander and me, and I left no stone unturned to get my revenge. Even before his plot I had hated him, revolted by his abominable practices, and I now busied myself with the attempt to expose him. I found plenty of allies, especially in the circle of Timocrates the Heracleot philosopher. But Avitus, the then governor of Bithynia and Pontus, restrained me, I may almost say with prayers and entreaties. He could not possibly spoil his relations with Rutilianus, he said, by punishing the man, even if he could get clear evidence against him. Thus arrested in my course, I did not persist in what must have been, considering the disposition of the judge, a fruitless prosecution.

[58] Among instances of Alexander’s presumption, a high place must be given to his petition to the Emperor: the name of Abonutichus was to be changed to Ionopolis; and a new coin was to be struck, with a representation on the obverse of Glycon, and, on the reverse, Alexander bearing the garlands proper to his paternal grandfather Asclepius, and the famous scimetar of his maternal ancestor Perseus.

[59] He had stated in an oracle that he was destined to live to a hundred and fifty, and then die by a thunderbolt. He had in fact, before he reached seventy, an end very sad for a son of Podalirius, his leg mortifying from foot to groin and being eaten of worms. It then proved that he was bald, as he was forced by pain to let the doctors make cooling applications to his head, which they could not do without removing his wig.

[60] So ended Alexander’s heroics. Such was the catastrophe of his tragedy; one would like to find a special providence in it, though doubtless chance must have the credit. The funeral celebration was to be worthy of his life, taking the form of a contest—for possession of the oracle. The most prominent of the impostors his accomplices referred it to Rutilianus’s arbitration which of them should be selected to succeed to the prophetic office and wear the hierophantic oracular garland. Among these was numbered the grey-haired physician Paetus, dishonoring equally his grey hairs and his profession. But Steward-of-the-Games Rutilianus sent them about their business ungarlanded, and continued the defunct in possession of his holy office.

[61] My object, dear friend, in making this small selection from a great mass of material has been twofold. First, I was willing to oblige a friend and comrade who is for me the pattern of wisdom, sincerity, good humor, justice, tranquillity, and geniality. But secondly I was still more concerned (a preference which you will be very far from resenting) to strike a blow for Epicurus, that great man whose holiness and divinity of nature were not shams, who alone had and imparted true insight into the good, and who brought deliverance to all that consorted with him. Yet I think casual readers too may find my essay not unserviceable, since it is not only destructive, but, for men of sense, constructive also.

Further Reading:

Swinish Herds and Pastafarians: Comedy as an Ideological Weapon

Lucian: Selected Dialogues (Oxford World’s Classics)